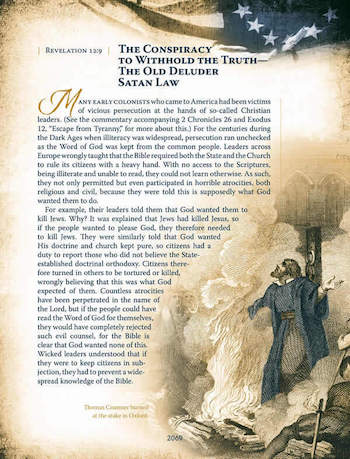

The Old Deluder Satan Law – America’s first public education law

What used to set America apart from the rest of the world is the quality of education we used to provide to our children. It was world class and at one time second to none. Today, not so much. Our so-called education system is no more than an indoctrination center for leftist ideology. History, at least real history, is no longer taught especially America’s history because it is so unique and successful. The reason is was so successful was because it was based on Christian principles. That statement causes liberals heads to explode but truth is truth.

Our educations primary school book, the New England Primer, that was used from the mid-1600s until the late 1800s is based solely on the Bible. All areas of life were taught using biblical principles. Liberals can deny it but historical facts prove it. The first laws providing public education for all children were passed in 1642 in Massachusetts and in 1647 in Connecticut and it was called the “Old Deluder Satan Law”. These colonists believed that the proper protection from civil abuses could only be achieved by eliminating Bible illiteracy.

“It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of Scriptures, as in former time. . . . It is therefore ordered . . . [that] after the Lord hath increased [the settlement] to the number of fifty householders, [they] shall then forthwith appoint one within their town, to teach all such children as shall resort to him, to write and read. . . . And it is further ordered, that where any town shall increase to the number of one hundred families or householders, they shall set up a grammar school . . . to instruct youths, so far as they may be fitted for the university.” [1] Continue reading →

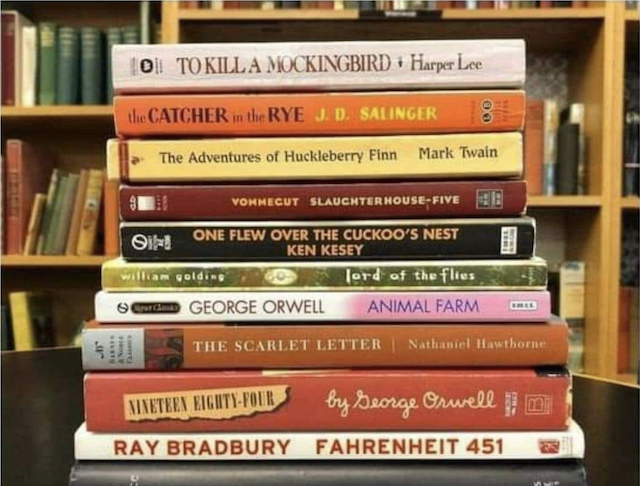

There are a lot of novels out there and choosing which to read isn’t always easy. But there are classics that we believe that everyone should read at least once. That is why we made a list of 25 classic novels that you should read. Keep reading to find out which books made our list!

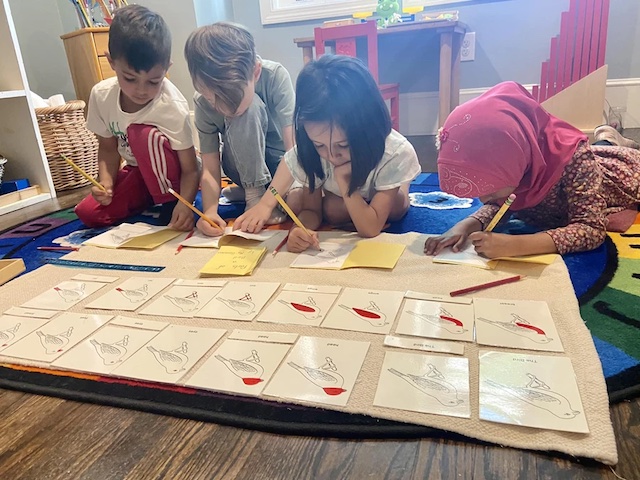

There are a lot of novels out there and choosing which to read isn’t always easy. But there are classics that we believe that everyone should read at least once. That is why we made a list of 25 classic novels that you should read. Keep reading to find out which books made our list! After-school activities are more than just ways to keep your child occupied once the school day is over. They play a pivotal role in shaping a child’s personality, instilling values, and building a diverse set of skills. During busy work seasons, it becomes especially important for parents to ensure that their children are engaged in productive activities that enrich their lives in multiple dimensions.

After-school activities are more than just ways to keep your child occupied once the school day is over. They play a pivotal role in shaping a child’s personality, instilling values, and building a diverse set of skills. During busy work seasons, it becomes especially important for parents to ensure that their children are engaged in productive activities that enrich their lives in multiple dimensions.

If you thought charter schools received anywhere near the same amount of funding as traditional public schools, then think again.

If you thought charter schools received anywhere near the same amount of funding as traditional public schools, then think again.

Memorization and recitation became part of my life through a club I was part of in middle and high school. With the club, I had the opportunity to recite patriotic speeches and poems along with chapters from the Bible in front of an audience of veterans, law enforcement officers, and first responders just about every month. I loved seeing how the words recited touched the people listening.

Memorization and recitation became part of my life through a club I was part of in middle and high school. With the club, I had the opportunity to recite patriotic speeches and poems along with chapters from the Bible in front of an audience of veterans, law enforcement officers, and first responders just about every month. I loved seeing how the words recited touched the people listening.  It’s around 200 CE, in Ephesus, an Aegean city of Greek roots, now a major hub of the Roman Empire. Meandering down marble-paved Curetes Street, a dweller is lost in the bustle of the town, procuring produce and wares in shops tucked beneath the colonnades, attending the public baths – even a conveniently placed brothel. It all plays out alongside merchants from across the Mediterranean, who disembark their ships to transport cargos and conduct business in the great depot between West and East. They make their way past the shrine to the emperor Hadrian and the nymphaeum of the emperor Trajan, bold reminders that the Ephesians, in their prosperity, are now part of the realm in faraway Rome. And there, culminating at the end of this lively thoroughfare at a slight angle, as though gradually revealing itself, lies a theatrical marble-clad façade of elegant Corinthian columns, exquisite reliefs and wordy inscriptions.

It’s around 200 CE, in Ephesus, an Aegean city of Greek roots, now a major hub of the Roman Empire. Meandering down marble-paved Curetes Street, a dweller is lost in the bustle of the town, procuring produce and wares in shops tucked beneath the colonnades, attending the public baths – even a conveniently placed brothel. It all plays out alongside merchants from across the Mediterranean, who disembark their ships to transport cargos and conduct business in the great depot between West and East. They make their way past the shrine to the emperor Hadrian and the nymphaeum of the emperor Trajan, bold reminders that the Ephesians, in their prosperity, are now part of the realm in faraway Rome. And there, culminating at the end of this lively thoroughfare at a slight angle, as though gradually revealing itself, lies a theatrical marble-clad façade of elegant Corinthian columns, exquisite reliefs and wordy inscriptions.

When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Rousmery Negrón and her 11-year-old son both noticed a change:

When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Rousmery Negrón and her 11-year-old son both noticed a change:  If you are a parent or a teacher, you most probably read stories to young children. Together, you laugh and point at the pictures. You engage them with a few simple questions. And they respond.

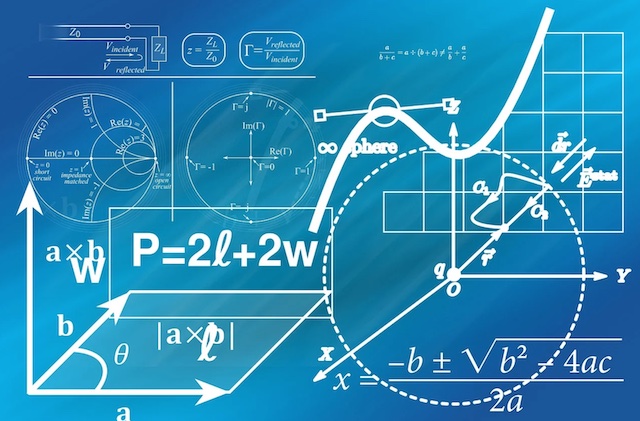

If you are a parent or a teacher, you most probably read stories to young children. Together, you laugh and point at the pictures. You engage them with a few simple questions. And they respond. A resurgence of interest in classical education has been evident in recent years. This has been due, in part, to a number of influential writings on regaining “lost” knowledge in our culture which have, in turn, inspired an increasing number of schools founded on a classical model. When surveying the landscape of classical education, it becomes evident that there is a clear vision available for the purpose of the study of humanities. What does not seem as clear, though, is the nature of mathematics in a classical education.

A resurgence of interest in classical education has been evident in recent years. This has been due, in part, to a number of influential writings on regaining “lost” knowledge in our culture which have, in turn, inspired an increasing number of schools founded on a classical model. When surveying the landscape of classical education, it becomes evident that there is a clear vision available for the purpose of the study of humanities. What does not seem as clear, though, is the nature of mathematics in a classical education. In 1930, 3 million American adults could not read. Most of those 1 million white illiterates and 2 million black illiterates were people over age fifty who had never been to school. (Regna Lee Wood)

In 1930, 3 million American adults could not read. Most of those 1 million white illiterates and 2 million black illiterates were people over age fifty who had never been to school. (Regna Lee Wood) My wife and I recently met with the principal of the school our daughter attends to discuss her education future.

My wife and I recently met with the principal of the school our daughter attends to discuss her education future.

What follows is the transcript of the 1920 newspaper clipping. The actual clip is at the end.

What follows is the transcript of the 1920 newspaper clipping. The actual clip is at the end.  An article on The Gateway Pundit for May 28th provided some information worth noting on what goes on in public schools and who is doing some of it. If you’ve had problems with Target over their “gay” pride merchandise you may find that is only the tip of the iceberg. The Gateway Pundit article tells us: “Retail giant Target has partnered with GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network) for years… GLSEN is a group that provides sexually explicit books to schools, pushes gender identity throughout public school curricula, and advocates policies that keep parents unaware of their child’s in-school gender transition… It was Barack Obama who first pushed sex education to kindergartners back in 2007 – he even pushed sex education to kiddies legislation… the media mostly hid this from the American public.” Sounds like King Barack the first really did have a plan to “fundamentally transform the United States” but he didn’t want the public to grasp just what it was!

An article on The Gateway Pundit for May 28th provided some information worth noting on what goes on in public schools and who is doing some of it. If you’ve had problems with Target over their “gay” pride merchandise you may find that is only the tip of the iceberg. The Gateway Pundit article tells us: “Retail giant Target has partnered with GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network) for years… GLSEN is a group that provides sexually explicit books to schools, pushes gender identity throughout public school curricula, and advocates policies that keep parents unaware of their child’s in-school gender transition… It was Barack Obama who first pushed sex education to kindergartners back in 2007 – he even pushed sex education to kiddies legislation… the media mostly hid this from the American public.” Sounds like King Barack the first really did have a plan to “fundamentally transform the United States” but he didn’t want the public to grasp just what it was!