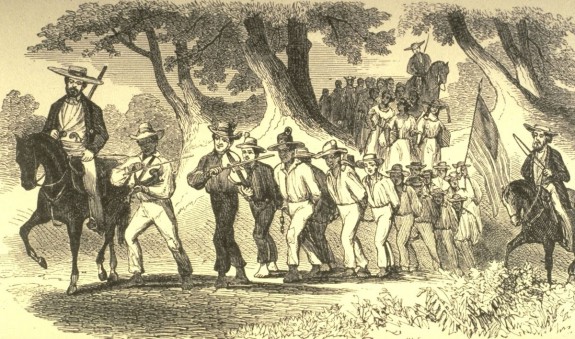

The third president knew that the whims of nature shaped Americans’ daily lives as farmers and enslavers

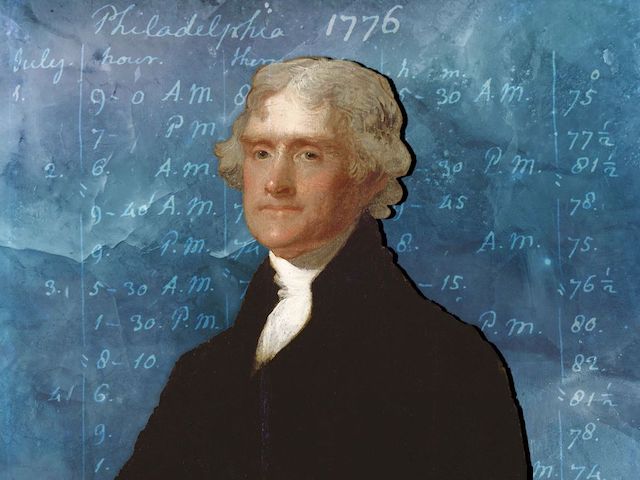

Between July 1776 and June 1826, Jefferson recorded weather conditions in 19,000 observations across nearly 100 locations. Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Wikimedia Commons under public domain and the Jefferson Weather and Climate Records

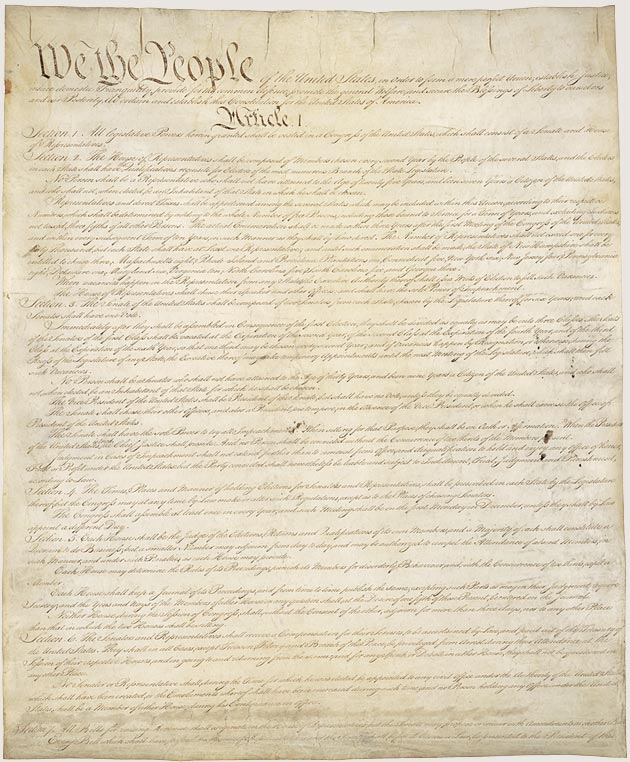

The Declaration of Independence was off to the press, so Thomas Jefferson spent July 4, 1776, in search of a decent thermometer. By lunchtime, a breeze ruffled the red brick of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Rain clouds tumbled in. A southwest wind swung through the streets, setting tavern signs to wheel and squeak, but the skies held. The city’s brutal summer melted into mild. Jefferson, a citizen scientist who tracked the weather wherever he went, grew eager to get a reliable read.

On Second Street, Jefferson nipped into John Sparhawk’s busy London Book-Store. Crowned with a unicorn and mortar logo, the emporium boasted new medicines, literature and “an assortment of curious hardware.” Continue reading

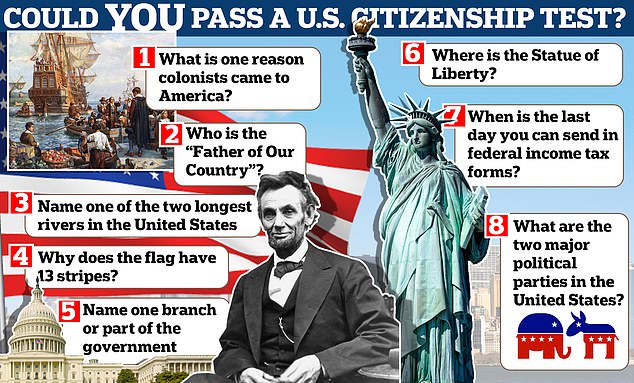

Government officials celebrated Independence Day by welcoming approximately 11,000 new citizens to the US during the July 4th holiday week.

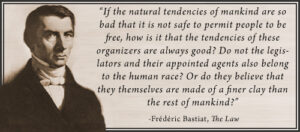

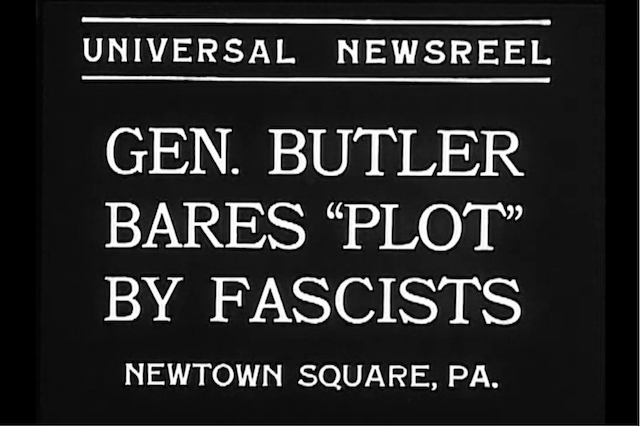

Government officials celebrated Independence Day by welcoming approximately 11,000 new citizens to the US during the July 4th holiday week. On May 29, 1935, in the midst of a Great Depression that would not end, the Supreme Court struck down a central piece of legislation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the National Industrial Recovery Act. In Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Court ruled that the entire scheme violated the U.S. Constitution.

On May 29, 1935, in the midst of a Great Depression that would not end, the Supreme Court struck down a central piece of legislation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the National Industrial Recovery Act. In Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Court ruled that the entire scheme violated the U.S. Constitution.

The

The  Is the above just a stupid question? Did our founders, the ones who hammered out the Constitution of the United States, several of whom became presidents, fail to understand the Constitution of the United States of America? Why would anyone even ask a question like that?

Is the above just a stupid question? Did our founders, the ones who hammered out the Constitution of the United States, several of whom became presidents, fail to understand the Constitution of the United States of America? Why would anyone even ask a question like that? Statesman John Calhoun, often vilified by modern sophisticates for the Confederacy’s embrace of his political philosophy, was in fact one of the greatest and most articulate champions of states’ rights, limited government, and strict federalism subsequent to the Founding Fathers.

Statesman John Calhoun, often vilified by modern sophisticates for the Confederacy’s embrace of his political philosophy, was in fact one of the greatest and most articulate champions of states’ rights, limited government, and strict federalism subsequent to the Founding Fathers.

~ PREFACE ~

~ PREFACE ~ ~ The Translation ~

~ The Translation ~

Charleston, South Carolina, is a city steeped in the rich history of the American Revolutionary War, offering a unique blend of historical sites and stories that bring the era of American independence to life. This article delves into several key locations and events that highlight Charleston’s significant role in the Revolutionary War.

Charleston, South Carolina, is a city steeped in the rich history of the American Revolutionary War, offering a unique blend of historical sites and stories that bring the era of American independence to life. This article delves into several key locations and events that highlight Charleston’s significant role in the Revolutionary War.  This amendment was introduced by James Madison to ensure that the Bill of Rights was not seen as an exhaustive list of the rights of the people. It acknowledges that there are other fundamental rights that exist even though they are not specifically mentioned in the Constitution. The Ninth Amendment serves as a constitutional safety net intended to make clear that individuals have other fundamental rights, in addition to those enumerated in the Constitution.

This amendment was introduced by James Madison to ensure that the Bill of Rights was not seen as an exhaustive list of the rights of the people. It acknowledges that there are other fundamental rights that exist even though they are not specifically mentioned in the Constitution. The Ninth Amendment serves as a constitutional safety net intended to make clear that individuals have other fundamental rights, in addition to those enumerated in the Constitution.

Banished for debasing the currency from his home city in what is now north-central Turkey,

Banished for debasing the currency from his home city in what is now north-central Turkey,