~ Forward ~

~ Forward ~

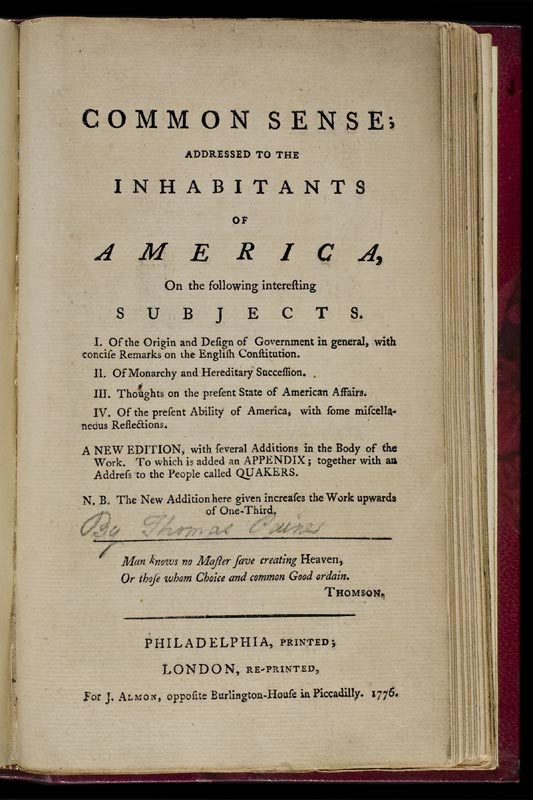

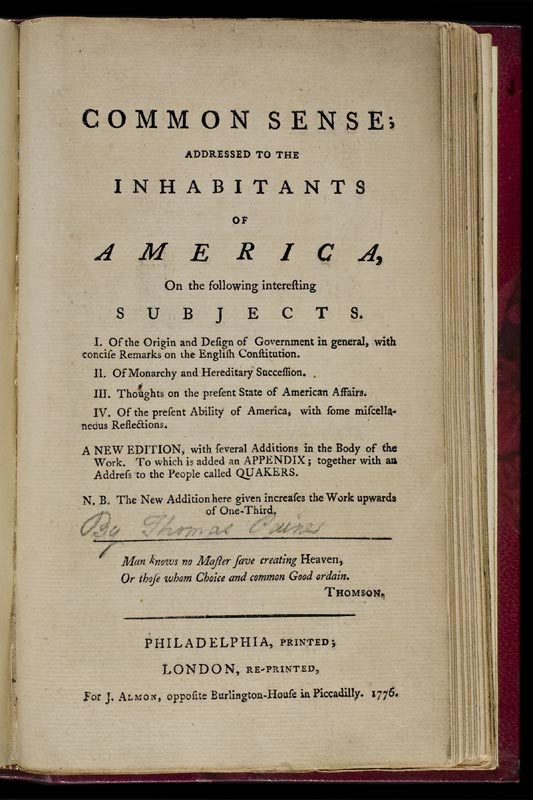

Published anonymously by Thomas Paine in January of 1776, Common Sense was an instant best-seller, both in the colonies and in Europe. It went through several editions in Philadelphia, and was republished in all parts of United America. Because of it, Paine became internationally famous.

“A Covenanted People” called Common Sense “by far the most influential tract of the American Revolution….it remains one of the most brilliant pamphlets ever written in the English language.”

Paine’s political pamphlet brought the rising revolutionary sentiment into sharp focus by placing blame for the suffering of the colonies directly on the reigning British monarch, George III.

First and foremost, Common Sense advocated an immediate declaration of independence, postulating a special moral obligation of America to the rest of the world. Not long after publication, the spirit of Paine’s argument found resonance in the American Declaration of Independence.

Written at the outset of the Revolution, Common Sense became the leaven for the ferment of the times. It stirred the colonists to strengthen their resolve, resulting in the first successful antic-olonial action in modern history.

Little did Paine realize that his writings would set fire to a movement that had seldom if ever been worked out in the Old World: sovereignty of the people and written constitutions, together with effective checks and balances in government.

Common Sense challenged the authority of the British government and the royal monarchy. The plain language that Paine used spoke to the common people of America and was the first work to openly ask for independence from Great Britain.

Paine has been described as a professional radical and a revolutionary propagandist without peer. Born in England, he was dismissed as an excise officer while lobbying for higher wages. Impressed by Paine, Benjamin Franklin sponsored Paine’s emigration to America in 1774.

In Philadelphia Paine became a journalist and essayist, contributing articles on all subjects to The Pennsylvania Magazine. After the publication of Common Sense, Paine continued to inspire and encourage the patriots during the Revolutionary War with a series of pamphlets entitled The American Crisis. Eventually, Paine went on to write The Rights of Man and The Age of Reason.

But, it all started with Common Sense, the writing that sparked an American Revolution.

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA, February 14, 1776

Introduction to the Third Edition

Introduction to the Third Edition

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not YET sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing WRONG, gives it a superficial appearance of being RIGHT, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason. As a long and violent abuse of power, is generally the Means of calling the right of it in question (and in Matters too which might never have been thought of, had not the Sufferers been aggravated into the inquiry) and as the King of England hath undertaken in his OWN RIGHT, to support the Parliament in what he calls THEIRS, and as the good people of this country are grievously oppressed by the combination, they have an undoubted privilege to inquire into the pretensions of both, and equally to reject the usurpation of either. In the following sheets, the author hath studiously avoided every thing which is personal among ourselves. Compliments as well as censure to individuals make no part thereof. Continue reading →

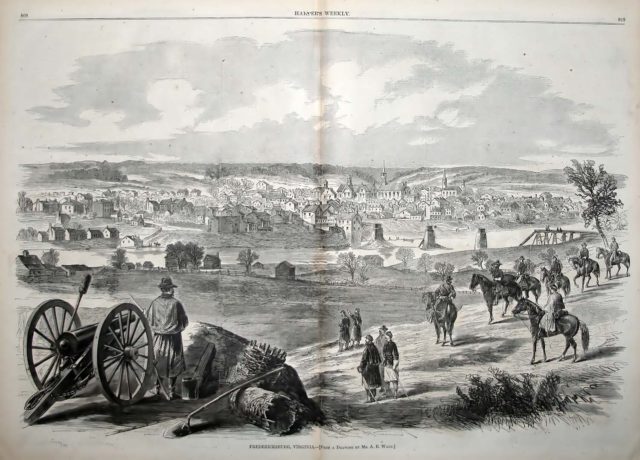

Although Jackson killed the central bank, fractional reserve banking remained in use by the numerous state chartered banks. This fueled economic instability in the years before the civil war. Still, the central bankers were out, and as a result American thrived as it expanded westward. The central bankers struggled to regain power of the bank, but to no avail. Finally, they reverted to the old central banker’s formula of war to create debt and dependency. If they couldn’t get their bank any other way, America could be brought to its knees by plunging it into a civil war, just as they had done in 1812, after, The First Bank of the U.S. was not rechartered.

Although Jackson killed the central bank, fractional reserve banking remained in use by the numerous state chartered banks. This fueled economic instability in the years before the civil war. Still, the central bankers were out, and as a result American thrived as it expanded westward. The central bankers struggled to regain power of the bank, but to no avail. Finally, they reverted to the old central banker’s formula of war to create debt and dependency. If they couldn’t get their bank any other way, America could be brought to its knees by plunging it into a civil war, just as they had done in 1812, after, The First Bank of the U.S. was not rechartered.

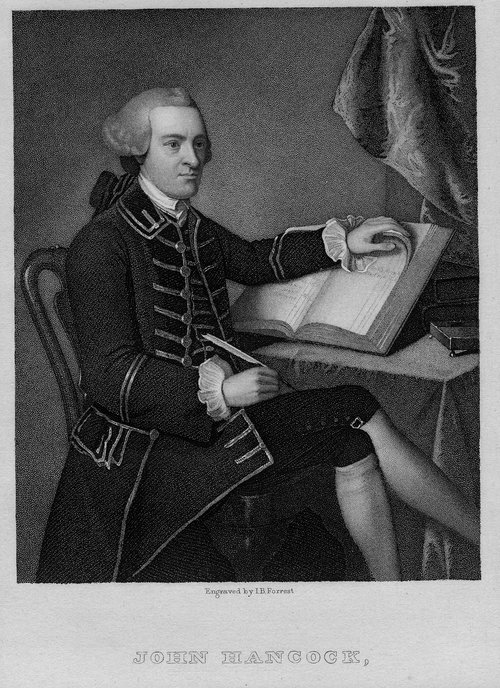

BOSTON, Massachussettes, March 5, 1774 – John Hancock, as fearless in his patriotism as he is eloquent in arguing the fine points of law, today told a cheering crowd on the Commons here that Americans stand as ready to die for liberty today as were the gallant victims of the Massacre of 1770.

BOSTON, Massachussettes, March 5, 1774 – John Hancock, as fearless in his patriotism as he is eloquent in arguing the fine points of law, today told a cheering crowd on the Commons here that Americans stand as ready to die for liberty today as were the gallant victims of the Massacre of 1770. The Boston Massacre was a street fight that occurred on March 5, 1770, between a “patriot” mob, throwing snowballs, stones, and sticks, and a squad of British soldiers. Several colonists were killed and this led to a campaign by speech-writers to rouse the ire of the citizenry.

The Boston Massacre was a street fight that occurred on March 5, 1770, between a “patriot” mob, throwing snowballs, stones, and sticks, and a squad of British soldiers. Several colonists were killed and this led to a campaign by speech-writers to rouse the ire of the citizenry. When Charles Adams published his book

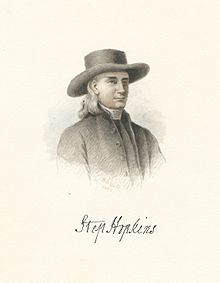

When Charles Adams published his book  Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785) Born in Scituate, R.I., Hopkins was a self-educated merchant shipper, surveyor, and colonial Governor. After joining the Revolutionary cause, he signed the Declaration of Independence. Hopkins entered into politics while in his twenties, serving in the General Assembly, and in 1739 – about when Saint Jago was born into slavery – he became Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. In 1742, he moved permanently to Providence and set up business as a merchant and ship builder. He continued to serve in politics and was a delegate from Rhode Island to the 1754 Albany convention that planned a military and political union of the colonies to help fight the impending French and Indian War (1754-1763). Although accepted by the convention, the plan was rejected by individual colonies and Great Britain.

Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785) Born in Scituate, R.I., Hopkins was a self-educated merchant shipper, surveyor, and colonial Governor. After joining the Revolutionary cause, he signed the Declaration of Independence. Hopkins entered into politics while in his twenties, serving in the General Assembly, and in 1739 – about when Saint Jago was born into slavery – he became Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. In 1742, he moved permanently to Providence and set up business as a merchant and ship builder. He continued to serve in politics and was a delegate from Rhode Island to the 1754 Albany convention that planned a military and political union of the colonies to help fight the impending French and Indian War (1754-1763). Although accepted by the convention, the plan was rejected by individual colonies and Great Britain.

~ Forward ~

~ Forward ~ Introduction to the Third Edition

Introduction to the Third Edition CAPE COD, 1620 ~ A group of fundamentalist religious immigrants from Europe joined together today on a tiny ship called the Mayflower harbored in Cape Cod. Their purpose was to sign an agreement before establishing a religious settlement in the area to be called Massachusetts. According to inside sources, the manifesto declares their intentions to use the settlement as a base for increasing their religious sect in the New World.

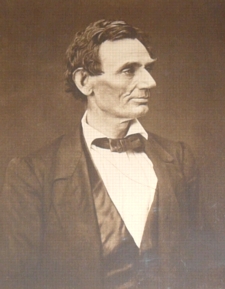

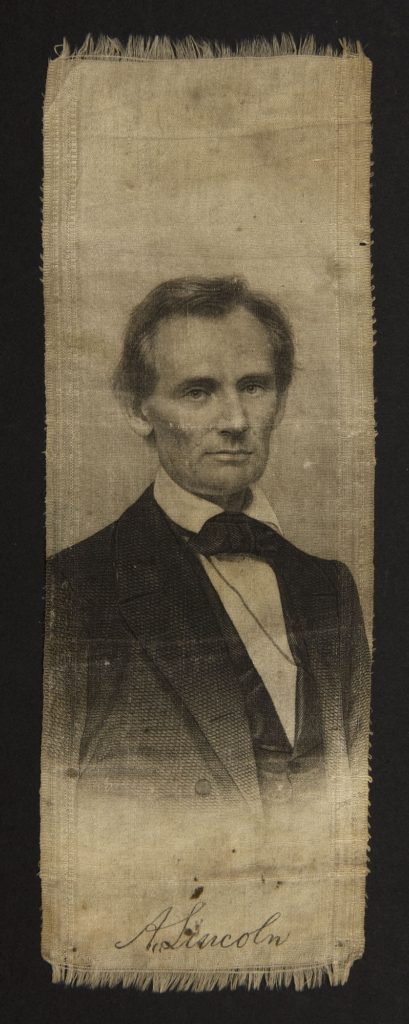

CAPE COD, 1620 ~ A group of fundamentalist religious immigrants from Europe joined together today on a tiny ship called the Mayflower harbored in Cape Cod. Their purpose was to sign an agreement before establishing a religious settlement in the area to be called Massachusetts. According to inside sources, the manifesto declares their intentions to use the settlement as a base for increasing their religious sect in the New World. Springfield, Ill., June 16, 1858 ~ More than 1,000 delegates met in the Springfield, Illinois, statehouse for the Republican State Convention. At 5:00 p.m. they chose Abraham Lincoln as their candidate for the U.S. Senate, running against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas. At 8:00 p.m. Lincoln delivered the following address to his Republican colleagues in the Hall of Representatives. The title reflects part of the speech’s introduction, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” a concept familiar to Lincoln’s audience as a statement by Jesus recorded in all three synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke).

Springfield, Ill., June 16, 1858 ~ More than 1,000 delegates met in the Springfield, Illinois, statehouse for the Republican State Convention. At 5:00 p.m. they chose Abraham Lincoln as their candidate for the U.S. Senate, running against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas. At 8:00 p.m. Lincoln delivered the following address to his Republican colleagues in the Hall of Representatives. The title reflects part of the speech’s introduction, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” a concept familiar to Lincoln’s audience as a statement by Jesus recorded in all three synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke).

~ Introduction ~

~ Introduction ~ As I know you will be rejoiced at the glorious success that our Lord has given me in my voyage, I write this to tell you how in thirty-three days I sailed to the Indies with the fleet that the illustrious King and Queen, our Sovereigns, gave me, where I discovered a great many islands, inhabited by numberless people; and of all I have taken possession for their Highnesses by proclamation and display of the Royal Standard without opposition. To the first island I discovered I gave the name of San Salvador, in commemoration of His Divine Majesty, who has wonderfully granted all this. The Indians call it Guanaham. The second I named the Island of Santa Maria de Concepcion; the third, Fernandina; the fourth, Isabella; the fifth, Juana; and thus to each one I gave a new name. When I came to Juana, I followed the coast of that isle toward the west, and found it so extensive that I thought it might be the mainland, the province of Cathay; and as I found no towns nor villages on the sea-coast, except a few small settlements, where it was impossible to speak to the people, because they fled at once, I continued the said route, thinking I could not fail to see some great cities or towns; and finding at the end of many leagues that nothing new appeared, and that the coast led northward, contrary to my wish, because the winter had already set in, I decided to make for the south, and as the wind also was against my proceeding, I determined not to wait there longer, and turned back to a certain harbor whence I sent two men to find out whether there was any king or large city. They explored for three days, and found countless small communities and people, without number, but with no kind of government, so they returned.

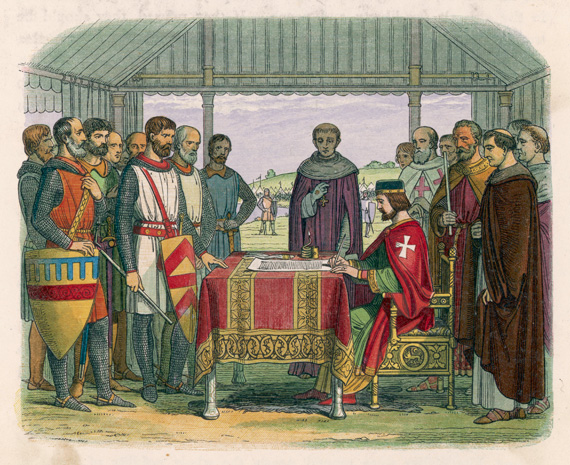

As I know you will be rejoiced at the glorious success that our Lord has given me in my voyage, I write this to tell you how in thirty-three days I sailed to the Indies with the fleet that the illustrious King and Queen, our Sovereigns, gave me, where I discovered a great many islands, inhabited by numberless people; and of all I have taken possession for their Highnesses by proclamation and display of the Royal Standard without opposition. To the first island I discovered I gave the name of San Salvador, in commemoration of His Divine Majesty, who has wonderfully granted all this. The Indians call it Guanaham. The second I named the Island of Santa Maria de Concepcion; the third, Fernandina; the fourth, Isabella; the fifth, Juana; and thus to each one I gave a new name. When I came to Juana, I followed the coast of that isle toward the west, and found it so extensive that I thought it might be the mainland, the province of Cathay; and as I found no towns nor villages on the sea-coast, except a few small settlements, where it was impossible to speak to the people, because they fled at once, I continued the said route, thinking I could not fail to see some great cities or towns; and finding at the end of many leagues that nothing new appeared, and that the coast led northward, contrary to my wish, because the winter had already set in, I decided to make for the south, and as the wind also was against my proceeding, I determined not to wait there longer, and turned back to a certain harbor whence I sent two men to find out whether there was any king or large city. They explored for three days, and found countless small communities and people, without number, but with no kind of government, so they returned.  Although Magna Carta failed to resolve the conflict between King John and his barons, it was reissued several times after his death.

Although Magna Carta failed to resolve the conflict between King John and his barons, it was reissued several times after his death.  During the process of compiling and editing the first volume of AMERICA: The Grand Illusion ~ Book I: Orphans of the Storm, I had occasion to work with my twelve year old granddaughter, Taylor (whose name fittingly works its way into this tale) on a history project for school, dealing with the War Between the States (which we have covered extensively on this site, but will eventually move into a category of its own). Needless to say, her teacher has been compromised in her education, and is subsequently passing her ignorance of American history onto the next generation of ill-informed children.

During the process of compiling and editing the first volume of AMERICA: The Grand Illusion ~ Book I: Orphans of the Storm, I had occasion to work with my twelve year old granddaughter, Taylor (whose name fittingly works its way into this tale) on a history project for school, dealing with the War Between the States (which we have covered extensively on this site, but will eventually move into a category of its own). Needless to say, her teacher has been compromised in her education, and is subsequently passing her ignorance of American history onto the next generation of ill-informed children.