PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania, April 1861 – The following is a narrative represented as the 1859 reminisces of one, ninety-nine year old Anthony Sherman, an alleged witness to General George Washington at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777, at which time Washington had purportedly told an officer of the Continental Army of an angel’s prophetic revelations of America’s future.

PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania, April 1861 – The following is a narrative represented as the 1859 reminisces of one, ninety-nine year old Anthony Sherman, an alleged witness to General George Washington at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777, at which time Washington had purportedly told an officer of the Continental Army of an angel’s prophetic revelations of America’s future.

Originally published by Charles W. Alexander (using the name of Wesley Bradshaw, Esq.), copied from a reprint in the National Tribune. Vol. 4, No. 12, December, 1880.

As time has gone on, many believe this story to be true, yet it is apparent that the story penned by Mr. Alexander for The Soldier’s Casket, a publication for Civil War veterans at the outbreak of the War Between the States, was written more for political reasons long after Washington’s death. And yet it remains a fitting addition to this volume, for it was said, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Continue reading

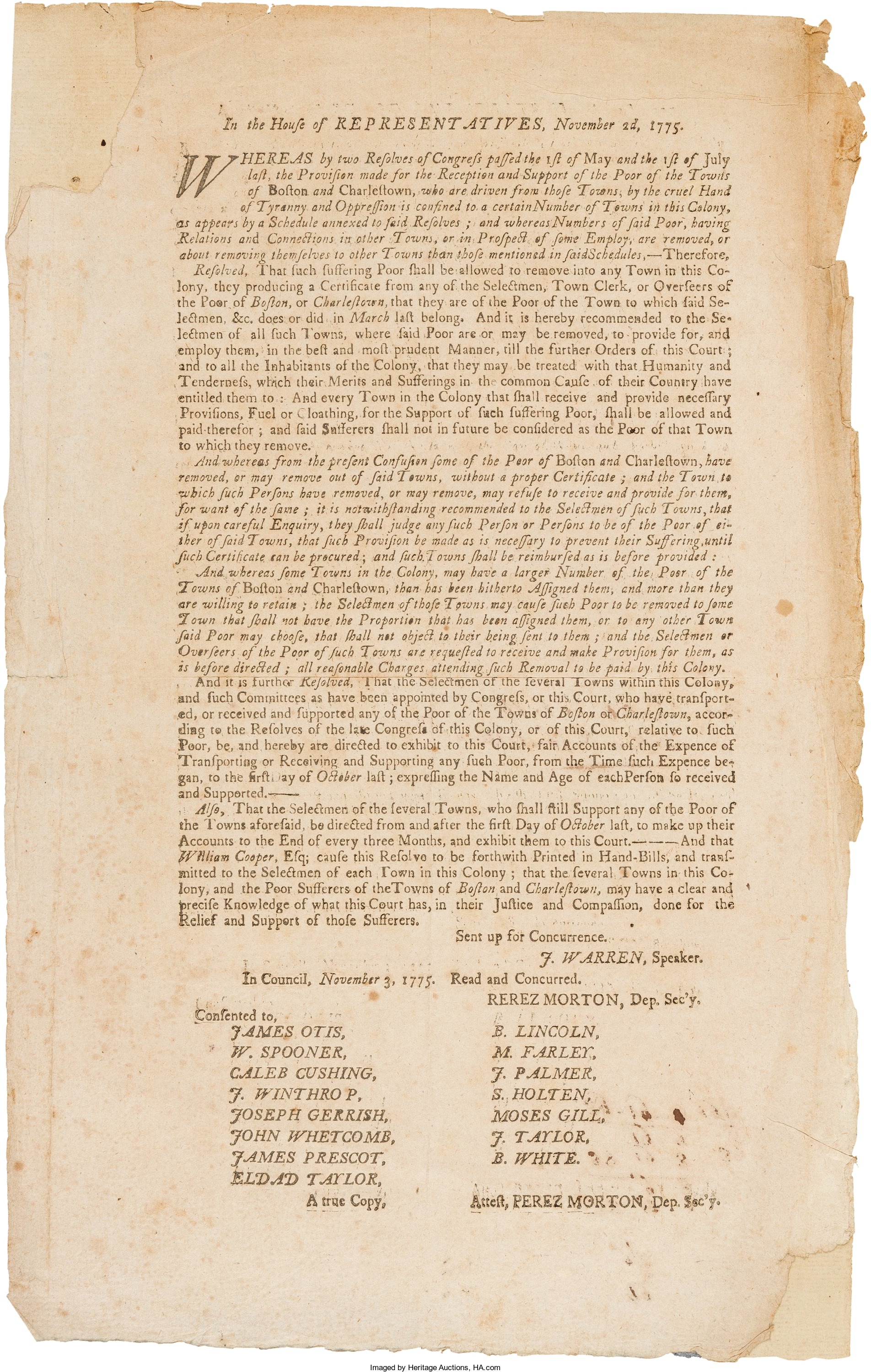

November 15, 1777 – The Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, the first constitution of the United States, on this date. However, ratification of the Articles of Confederation by all thirteen states did not occur until March 1, 1781. The Articles created a loose confederation of sovereign states and a weak central government, leaving most of the power with the state governments. The need for a stronger Federal government soon became apparent and eventually led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

November 15, 1777 – The Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, the first constitution of the United States, on this date. However, ratification of the Articles of Confederation by all thirteen states did not occur until March 1, 1781. The Articles created a loose confederation of sovereign states and a weak central government, leaving most of the power with the state governments. The need for a stronger Federal government soon became apparent and eventually led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

Poughkeepsie, New York, 1787 – The youngest of the vital young men who hammered into form the Federal Constitution derided the fears of conservative New Yorkers that establishment of the national government would mean the extinction of State sovereignty – a fear so strong among the older New York hierarchy that it still threatened older New York ratification of the Constitution.

Poughkeepsie, New York, 1787 – The youngest of the vital young men who hammered into form the Federal Constitution derided the fears of conservative New Yorkers that establishment of the national government would mean the extinction of State sovereignty – a fear so strong among the older New York hierarchy that it still threatened older New York ratification of the Constitution. September 17, 1796 – George Washington’s Farewell Address announced that he would not seek a third term as president. In his farewell Presidential address, while devoting much of the address to domestic issues of the time, advised American citizens to view themselves as a cohesive unit and avoid political parties and sectionalism as a threat to national unity, also warning to be wary of attachments and entanglements with other nations.

September 17, 1796 – George Washington’s Farewell Address announced that he would not seek a third term as president. In his farewell Presidential address, while devoting much of the address to domestic issues of the time, advised American citizens to view themselves as a cohesive unit and avoid political parties and sectionalism as a threat to national unity, also warning to be wary of attachments and entanglements with other nations.

September 17, 1787 – The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because the delegations from only two states were at first present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing Articles, the Convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected – directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.

September 17, 1787 – The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because the delegations from only two states were at first present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing Articles, the Convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected – directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.

and time? The terms, “snivelers” or “whiners” would translate into the “snowflakes” of today. ~

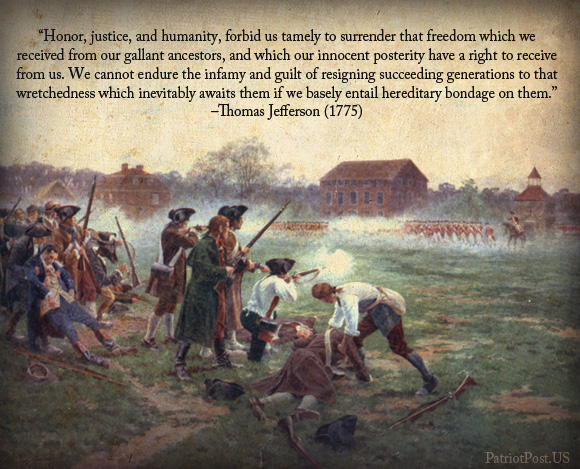

and time? The terms, “snivelers” or “whiners” would translate into the “snowflakes” of today. ~  In his original draft of the Declaration, Jefferson denounced the slave trade as an “execrable commerce …this assemblage of horrors,” a “cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberties.” If there had been inclusion of his words of the issue, slavery and the slave trade in the United States, would have been abolished.

In his original draft of the Declaration, Jefferson denounced the slave trade as an “execrable commerce …this assemblage of horrors,” a “cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberties.” If there had been inclusion of his words of the issue, slavery and the slave trade in the United States, would have been abolished. Richmond, Virginia; June 5, 1788, in the Virginia Convention, called to ratify the Constitution of the United States.

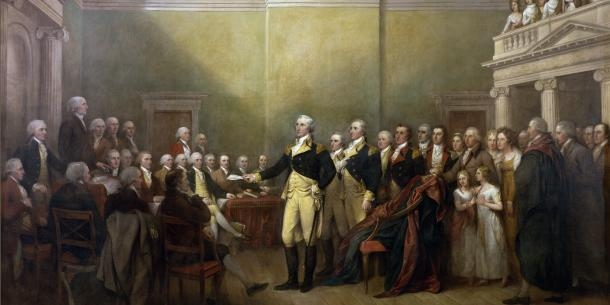

Richmond, Virginia; June 5, 1788, in the Virginia Convention, called to ratify the Constitution of the United States. NEW YORK CITY, New York, 1789 – On April 30, George Washington the Nation’s first chief executive took his oath of office in the City of New York on the balcony of the Senate Chamber at Federal Hall on Wall Street. The first Electoral College had unanimously elected General Washington President, and John Adams was elected Vice President because he received the second greatest number of votes. Under the rules, each elector cast two votes. The Chancellor of New York and fellow Freemason, Robert R. Livingston administered the oath of office. The Bible on which the oath was sworn belonged to New York’s St. John’s Masonic Lodge. The new President gave his inaugural address before a joint session of the two Houses of Congress assembled inside the Senate Chamber.

NEW YORK CITY, New York, 1789 – On April 30, George Washington the Nation’s first chief executive took his oath of office in the City of New York on the balcony of the Senate Chamber at Federal Hall on Wall Street. The first Electoral College had unanimously elected General Washington President, and John Adams was elected Vice President because he received the second greatest number of votes. Under the rules, each elector cast two votes. The Chancellor of New York and fellow Freemason, Robert R. Livingston administered the oath of office. The Bible on which the oath was sworn belonged to New York’s St. John’s Masonic Lodge. The new President gave his inaugural address before a joint session of the two Houses of Congress assembled inside the Senate Chamber.

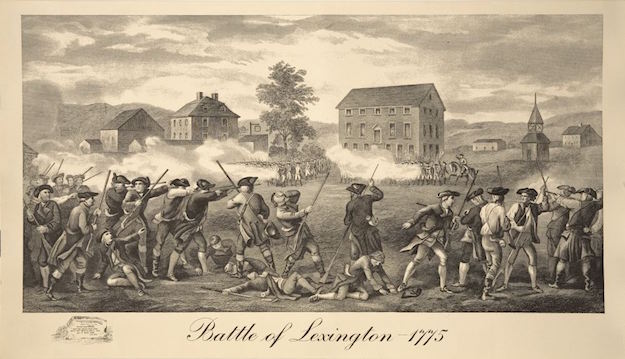

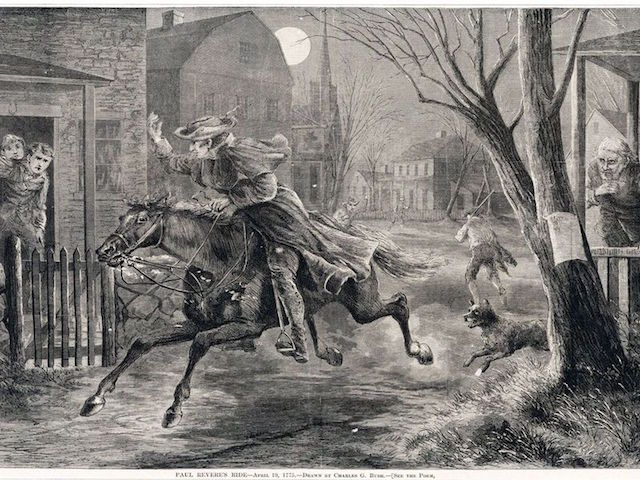

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Listen, my children, and you shall hear