“A government is like everything else: to preserve it, we must love it.”

Today’s schools teach only the ugliest parts of US history, turning students off from civic engagement. Shutterstock

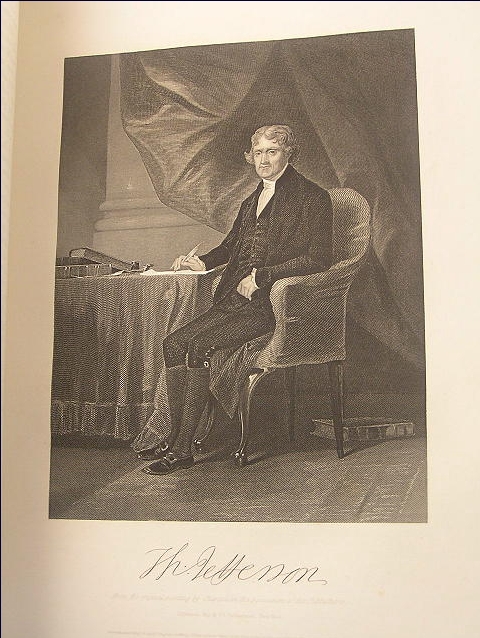

When he was young, Thomas Jefferson carefully copied those words — a quote from the great political philosopher Montesquieu — into his “commonplace book,” the private journal he kept as a student for future inspiration.

“Everything, therefore, depends on establishing this love in a republic,” the passage continued. “And to inspire it ought to be the principal business of education.”

Thomas Jefferson thought teaching children American History, at an early age, should be a central focus.

Thomas Jefferson thought teaching children American History, at an early age, should be the mission of public schools.

In other words, as Jefferson might put it today to our public schools: You had one job — and you failed.

“Today we talk as if it’s all about college and career readiness,” education scholar Michael J. Petrilli told The Post. “But going back to the 1780s, the argument in favor of having public education at all has been first and foremost to develop democratic citizens.”

In “How to Educate an American: The Conservative Vision for Tomorrow’s Schools” (Templeton Press), Petrilli collects essays from 20 prominent conservative thinkers who survey the current state of America’s schools. The result is a passionate case for a return to Jefferson’s values after decades spent chasing higher graduation rates, glittering college-enrollment numbers and top standardized-test scores.

Those obsessions peaked with the Common Core curriculum, which the Obama administration pushed onto the states — sparking furious backlash from many parents and teachers, who found that technocratic education reforms led to a vacuous mania for the mechanics of math and reading.

“We just don’t teach our young kids anything,” Petrilli said. “Teaching ‘reading comprehension’ with no content is as boring as it sounds, and as ineffective as it sounds.”

Common Core was the culmination of a long-term trend that enshrined math and reading instruction as the top priority of early elementary education, leaving history and civics as an afterthought to be squeezed in once test prep was complete — if at all.

Instead, teachers should take a page out of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s book, whose “Hamilton” tells a full story — slavery as well as heroism.

Petrilli argues that teachers should take a page out of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s book, whose “Hamilton” tells a full story — slavery as well as heroism.AP

A few years after Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and helped win the nation’s freedom, he made a commitment to the words he had once inscribed in his notebook.

Back in his home state of Virginia, he launched a campaign to establish a free public education system, a pillar of his plan to secure the long-term health of America’s young democracy.

For children aged 6 to 8, he wrote, the study of American history should be a central focus of the school day. A strong early grounding in history would ensure that these future citizens would cherish and sustain the republic the Founders had won for them, Jefferson believed.

“History, by apprising them of the past, will enable them to judge of the future,” he wrote.

Then again, students in Jefferson’s day didn’t have to grapple with The 1619 Project.

That controversial effort, launched by the New York Times last year, is a wholesale reinterpretation of America’s founding that damns the ideals laid out in Jefferson’s Declaration as “false when they were written.”

Instead, its authors declared, our national history is racist to the core, rooted in slavery and white supremacy. They fleshed out the concept in a 100-page magazine supplement that has already been added to the history curriculum in 3,500 US high schools.

Developed by The New York Times Magazine, the 1619 Project re-examines the legacy of slavery in the United States and has been added to the history curriculum in 3,500 US high schools.NY Post photo composite

“1619 is a perfect example of what has gone so wrong in American schools when it comes to history,” Petrilli said. “It isn’t teaching history, warts and all; it’s only just the warts.”

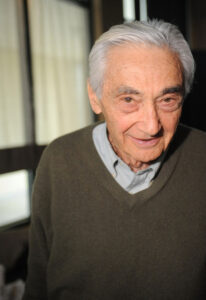

It’s the latest in a long line of critical revisions of the American story, going back to Howard Zinn’s influential “A People’s History of the United States.” Zinn’s book, published in 1980, aimed to tell “US history from the ground up” — that is, stripped of its traditional heroes.

And while the critical approach has a valid role in the classroom, Petrilli contends, it does harm when it comprises our students’ only exposure to American history.

“In many schools, you are more likely to encounter the 1619 or Zinn version of history than anything positive,” he said. “We’re telling our young people that America is racist and oppressive and has only failed over the years to do right by the most vulnerable, rather than that we were founded with incredible ideals that we have sometimes failed to live up to.”

Given the pervasive influence of Zinn and his successors, the education of most Americans under the age of 40 has been clouded by that cynical perspective on our heritage.

Perhaps the decay of old civic norms and the acceleration of political strife in recent years is no coincidence.

Howard Zinn’s book, “A People’s History of the United States,” aimed to tell US history stripped of its traditional heroes. WireImage

In many US states, a single high-school history class is the only civics instruction that future voters ever receive. Eight states don’t even make the study of American history a graduation requirement.

“Civic education requires knowledge of history,” writes contributor Eliot Cohen, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and one of the book’s contributors — not only to comprehend our government and its laws, “but also to develop an attachment to them.”

“One has to think that the architects did remarkable work,” he argues, and that they built “a precious edifice like none other.”

Such respect must be nurtured from an early age with “history that inspires,” adds Stanford University professor William Damon in his section of the book — what he calls “patriotic history.”

Genuine, active citizenship is driven by a sense of civic purpose, Damon writes. “The key motivational component is a positive attachment to one’s society,” a feeling that the ancient Greeks called patriotism.

Genuine, active citizenship is driven by a sense of civic purpose, Damon writes. “The key motivational component is a positive attachment to one’s society,” a feeling that the ancient Greeks called patriotism.

Even though “patriotism is one of the most politically incorrect words in education today,” Damon says, this sense of attachment and identification is the only thing that makes democratic participation meaningful. “To acquire civic purpose, students need to care about their country,” he writes. “Schools should begin with the positive” to cultivate that motivating spirit.

To do so, teachers need to hold up our country’s heroes and heroines as worthy models — rather than focus myopically on their failings and foibles.

“In our popular culture, there’s a real hunger for this material,” Petrilli said, citing the Broadway show “Hamilton” as an example.

“Lin-Manuel Miranda didn’t sugarcoat anything: Slavery was part of the story, and as he showed, it was hotly debated back then,” he explained. “But he also demonstrated the ideals and the seriousness of the founders, and explained how these ideals were revolutionary back then.”

Those storylines appeal to kids just as much as they do to adults, he said — giving teachers, as well as parents, plenty of opportunities to build up historical literacy.

Author Michael Petrilli is arguing for more history and civics lessons in public schools — to encourage a love of America.

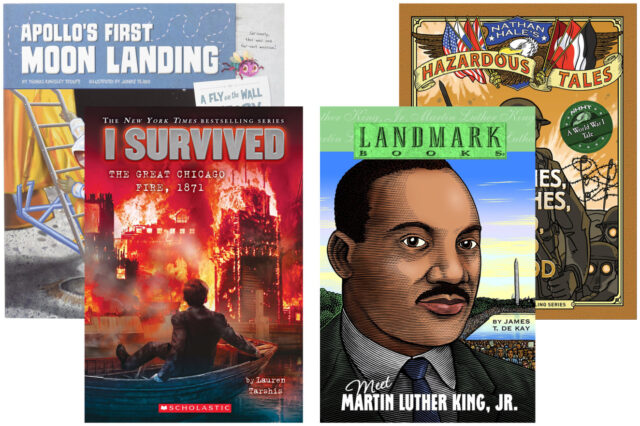

“Because Common Core called for a greater focus on nonfiction reading material in the early grades, publishers have put out more books for children on history themes,” Petrilli said — everything from straightforward biographies of important Americans to rollicking graphic novels like “Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales,” which retell stories like the Donner Party disaster, the battle of the Alamo, and more.

There’s a place for historical fiction, too, he noted. “Look at the American Girl dolls, which have been popular for 20 years,” he said. Each historical character comes with her own series of chapter books, widely read by preteen girls.

Not so long ago, public schools were expected to serve as a source of solidarity among Americans, a major force in the formation of a national spirit and culture.

“Growing up in a multiracial, multiethnic environment, American students already share fewer commonalities than those from more homogenous nations,” the Manhattan Institute’s Kay Hymowitz points out in another essay in the book. A cohesive sense of national unity in such a culture requires active effort to maintain.

“Educators have all but abandoned the mission of creating an e pluribus unum, of instilling a sense of common history and culture,” Hymowitz writes — in favor of a devotion to diversity that seems to be pulling us farther apart than before.

“Educators have all but abandoned the mission of creating an e pluribus unum, of instilling a sense of common history and culture,” Hymowitz writes — in favor of a devotion to diversity that seems to be pulling us farther apart than before.

“Schools can’t duck this responsibility,” Petrilli argued. “It’s the number one reason we have public schools in the first place.”

The idea isn’t to shield students from the painful parts of American history, he said, “but to tell the story in all its richness. Rather than this very cynical view that it was all a fraud, we can take a position of gratitude for the people who came before us who worked to make a more perfect union.

“It’s also a more constructive story: This is your inheritance, and you can be a part of living up to those ideals. I think that’s something young people can get behind.”

Give kids a rich history

Children’s publishers have rediscovered history — and kids are diving in. These series are just a sampling of the increasingly popular genre.

Children’s publishers have rediscovered history — and kids are diving in. These series are just a sampling of the increasingly popular genre.

Fly on the Wall History (grades 1-3): A pair of cute cartoon insects offer you-are-there comments on topics like Paul Revere’s ride and the Wright Brothers’ flight.

Landmark (gr. 1-3 and gr. 6-9): Classic biographies and brief histories, repackaged with new illustrations, on Martin Luther King Jr., the Battle of Gettysburg, Thomas Edison, the Salem witch trials and more.

I Survived (gr. 2-5): Stealthy history lessons are tucked into these fictionalized first-person tales of kids battling through the Chicago fire, the San Francisco earthquake, and even the Great Molasses Flood that killed 21 Bostonians in 1919.

Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales (gr. 4-7): Irreverent graphic novels packed with gore, action and the gross-out humor kids adore. The titles alone (“Donner Dinner Party: The Worst Family Road Trip Ever”) will get preteens turning pages.

Written by Mary Kay Linge for The New York Post ~ February 22, 2020