Writers from the 1920s to Prime You for the 2020s

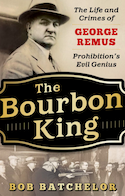

Prohibition-era criminal mastermind George Remus—unlike other 1920s gangland kingpins like Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, or Charles “Lucky” Luciano—has been largely forgotten. The “King of the Bootleggers,” who led a raucous life highlighted by forming a bourbon empire that accumulated billions of dollars in today’s money, later murdered his wife Imogene in cold blood in Cincinnati’s Eden Park, which led to a sensational Jazz Age trial and an overhaul of criminal insanity laws.

Prohibition-era criminal mastermind George Remus—unlike other 1920s gangland kingpins like Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, or Charles “Lucky” Luciano—has been largely forgotten. The “King of the Bootleggers,” who led a raucous life highlighted by forming a bourbon empire that accumulated billions of dollars in today’s money, later murdered his wife Imogene in cold blood in Cincinnati’s Eden Park, which led to a sensational Jazz Age trial and an overhaul of criminal insanity laws.

In researching Remus for my new book, The Bourbon King, I found the connection to other things “lost” from history became more pronounced. So much wonderful literature was published in the 1920s, but has since been basically consigned to the dustbin. We all know the novels and works that are read and re-read, listed on high school and college syllabi, but the literary landscape is littered with lost bestsellers and forgotten monographs. Many books from the 1920s can provide deep insight on current pressing issues, from extensive presidential corruption to clashes over alcohol and marijuana policies. Race, our most pervasive and harrowing challenge, (then and now) was a principal concern.

In researching Remus for my new book, The Bourbon King, I found the connection to other things “lost” from history became more pronounced. So much wonderful literature was published in the 1920s, but has since been basically consigned to the dustbin. We all know the novels and works that are read and re-read, listed on high school and college syllabi, but the literary landscape is littered with lost bestsellers and forgotten monographs. Many books from the 1920s can provide deep insight on current pressing issues, from extensive presidential corruption to clashes over alcohol and marijuana policies. Race, our most pervasive and harrowing challenge, (then and now) was a principal concern.

Reading about forgotten books and authors nearly 100 years later is a haunting exercise. We know that the Great Depression is just on the horizon and that many of the writers of that age will struggle and suffer. We also feel the angst, awe, and crushing pull of the America they experienced. The nation has advanced in so many areas, yet the basic human condition seems all too familiar—similar social issues force us to confront our decay. In this spirit, here are ten books from the 1920s that are worth reading now.

Ole Edvart Rölvaag, Giants in the Earth (1927)

Ole Edvart Rölvaag, Giants in the Earth (1927)

Traveling into the American heartland, Rölvaag’s Giants in the Earth focuses on a Norwegian family’s struggles as they attempt to set up a homestead in the Dakota Territory. Rölvaag’s hero, Per Hansa, is based on some of his own experiences as a Norwegian immigrant. Hansa retains an optimistic outlook, despite the severity of his life. His wife Beret is a sterner personality, highly religious and less optimistic. Dealing with the challenges of assimilation, arriving in a strange land, language issues, and the loneliness of immigrant life, Giants in the Earth is a haunting portrayal of prairie life.

Edna Ferber, So Big (1924)

Edna Ferber, So Big (1924)

Winner of the 1925 Pulitzer Prize, Edna Ferber’s So Big tackles important topics, like immigration, the role of art and culture in society, and how one lives her best life. So Big is a bit Gatsby-like without the New York City backdrop and the upper reaches of moneyed society. Instead, the novel follows the life of Selina Peake, a young woman with many skills, whose life is turned upside down by the loss of her father and young husband, leaving her alone to raise her young son Dirk on the dirt farm that her husband left behind. The young man becomes a successful bond salesman, rich and famous. Dirk later laments that he didn’t stay with architecture, his boyhood dream (shared by his mother), an artistic career path that would have led to happiness.

So Big was the important book that critics hoped Ferber would someday write. At publication, one reviewer claimed it was “not the Great American Novel but it certainly falls in the category of ‘one of the great.’”

Gene Stratton-Porter, The Keeper of the Bees (1925)

Gene Stratton-Porter, The Keeper of the Bees (1925)

The public devoured The Keeper of the Bees by Gene Stratton-Porter, published a year after her untimely death from a late 1924 car accident. The novel is representative of the author’s themes: wide-ranging optimism and pro-conservation, which she strongly advocated in the early 1920s as an antidote to the roughness of the age. Keeper is the story of ailing war hero James Lewis Macfarlane, dismissed after the war, even though he still suffers from poisoning and other wartime consequences. Eventually making his way to a California bee farm, Macfarlane is on a road toward recovery. The salty air of the Pacific Ocean eventually leads him to a kind of robustness and renewed sense of vigor.

Stratton-Porter’s ideas remain significant, still at the center of today’s news, certainly when large swaths of people are dealing more or less daily with “Trump Anxiety Disorder,” controversies around climate, and, more pointedly, PTSD and war wounds. And, of course, today’s crisis with bees, the subject at the heart of Stratton-Porter’s novel.

Nella Larsen, Passing (1929)

Nella Larsen, Passing (1929)

Let’s just make the case that Nella Larsen, a trailblazing librarian and writer who was part of the Harlem Renaissance movement, should be more widely read if the reader hopes to more fully understand the context, history, and evolution of black life in the early 20th century. Passing, critically-acclaimed and set in Harlem, examines the lives of two women who were childhood friends, but then reconnect later in life and compare their experiences. Light-skinned Clare “passed” as white and married a white man, while Irene married a black man. Both women have white ancestry and lead complicated lives based on their decisions regarding how to deal with race and its consequences. By titling the novel Passing, Larsen certainly directs readers to the primary issue she confronts, but the book also demonstrates how race is tied into other complicated topics, particularly social standing, gender, and wealth.

Anzia Yezierska, Bread Givers (1925)

Anzia Yezierska, Bread Givers (1925)

Writer Anzia Yezierska’s life is a biopic waiting to happen—Jewish immigrant living on the Lower East Side, sordid love life, affair with philosopher John Dewey, screenwriter dubbed “the sweatshop Cinderella,” women’s rights activist, and much more.

George Currie, reviewing Yezierska’s novel in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle explained, “The reader is looking at real people, living with them, suffering their little scandals, dreading the arrival of the rent lady, stuffing buttlerless bread to ease the gnawing pains of hunger.” Ultimately, he applauds Bread Givers as “a perfect example of high art in heartthrobs.” The realistic portrait of lives lived in the Jewish ghettoes of early 20th century New York City remain instructive.

Viña Delmar, Bad Girl (1928)

Viña Delmar, Bad Girl (1928)

Although a cautionary tale of lower middle-class life, Viña Delmar’s Bad Girl addressed taboo topics in the late 1920s, including premarital sex and pregnancy. The lurid themes caught people’s attention, but the book then became a runaway bestseller when the city of Boston banned it.

Delmar became so famous from Bad Girl that she took Hollywood by storm. The novel was turned into a film, out in 1931. The movie was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, while Frank Borzage won the Academy Award for Directing.

James Harvey Robinson, The Mind in the Making (1921)

James Harvey Robinson, The Mind in the Making (1921)

Robinson, a historian who co-founded the New School in 1919, wrote about history as a discipline for a popular audience. His idea was straightforward, but revolutionary at the time—a combination of interdisciplinary research and utilizing history to provide context for solving humankind’s most difficult challenges. Robinson believed that critical and creative thinking was the primary answer for addressing problems in what he viewed as a fast-moving interconnected world. H.G. Wells was a fan, exclaiming that The Mind in the Making would serve as “marking a new and characteristic American initiative in the world’s thoughts and methods.”

So soon after the horrors of World War I, readers were searching for answers. What Robinson viewed as the world’s foremost problem seems eerily perceptive today: “We have available knowledge and ingenuity and material resources to make a far fairer world than that in which we find ourselves, but various obstacles prevent our intelligently availing ourselves of them.”

Rudolph Fisher, The Walls of Jericho (1928)

Rudolph Fisher, The Walls of Jericho (1928)

Rudolph Fisher’s The Walls of Jericho emerged from the burgeoning Harlem Renaissance as a comedic social satire of class issues in “high” and “low” Harlem. Fisher deftly blends ideas of class, race, and money into a panoramic portrait of society that simultaneously illuminates these ideas, while also showing how they blur by way of individuals’ understanding of themselves and those around them.

Newspapers in the 1920s debated, detailed, and described how “Harlemese,” the general term for African-American slang, had become commonplace. Fisher created an 11-page glossary about Harlemese “expurgated and abridged” in the novel, featuring 110 slang terms, from the playful “Haul It” (“Haul hiney. Depart in great haste. Catch air.”) to the suggestive “Bump the Bump (“A forward and backward swaying of the hips. Said to be an excellent aphrodisiac.”)

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, The Home-Maker (1924)

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, The Home-Maker (1924)

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, an education advocate and early supporter of the Montessori methodology, was also an accomplished popular novelist. The Home-Maker addresses gender and marriage roles via the plight of Evangeline Knapp, a woman who fears staying at home to raise her children, but whose life changes dramatically when her husband Lester is maimed. They reverse roles—the wife entering the business world, while Lester successfully raises their two children. Like all family issues, The Home-Maker is much deeper than it appears at first glance, deftly exploring society’s labels and their impact on people’s lives.

An authority no less noted than Eleanor Roosevelt once claimed that Canfield Fisher was one of the ten most influential women in the nation, but much of her work across adult and young adult fiction and nonfiction is no longer read.

Sinclair Lewis, Babbitt (1922)

Sinclair Lewis, Babbitt (1922)

Sinclair Lewis proves that a Nobel Prize winner can be forgotten. He may be the most famous (and bestselling) writer of his age that is largely unread today. Even worse, scholars have relegated Lewis to the trash heap. Yet, when I read Babbitt, I am left scratching my head over how far Lewis’s reputation has fallen.

In the midst of Trump’s America, one finds the novel a tutorial on middle America, a blueprint for not only how the reality show huckster came to power, but the secret desires that leave so many people (especially middle class corporate managers) existentially hollow. The gaping hole at the center of the novel (and so many people today) is the futility of the American Dream, not only in the elusive chase, but ever believing that achieving it will ultimately deliver happiness or satisfaction. We all know George Babbitt, his hometown boosterism and civic pride is the stuff of countless mid-sized cities and small towns. Babbitt’s plight provokes the reader and asks that we search for a something more authentic from life.

…and, because we are having so much fun with this list, I am going to add an eleventh, The Adding Machine, a 1923 play by Elmer Rice, because more people should be reading drama, along with novels and nonfiction.

Elmer Rice, The Adding Machine (1923)

Elmer Rice, The Adding Machine (1923)

A striking commentary of the rise of automation and stultifying consequences of business life, The Adding Machine is simply a masterpiece. Rice’s play influenced a generation of writers and can be felt today in the countless nameless, faceless office drones that suddenly realize they are the sausage in the sausage factory.

The Adding Machine’s antihero is Mr. Zero, an accountant who kills his boss when he finds that he will be replaced by a machine. In a Heaven-like place called Elysian Fields after he is hanged for the murder, Mr. Zero realizes that he has lived an unfulfilled life, both despising the machine that replaces him, but also having gone through life in a robotic, lifeless fashion. Looking at issues of individuality, sexual repression, and mechanization, The Adding Machine may cause readers who have withered in corporate settings relive those awful times, but it also opens a window toward fulfillment.

Written by Bob Batchelor for The Literary Hub ~ September 13, 2019