Frederic Bastiat’s “The Law,” written near the end of his life in 1850 France, is a symphony of ideas.

Frederic Bastiat’s “The Law,” written near the end of his life in 1850 France, is a symphony of ideas.

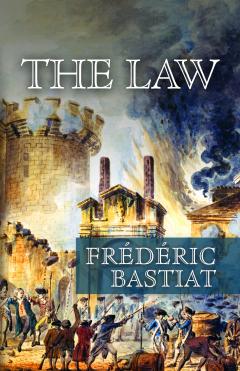

My high school economic students are reading their first book of the year, one that is close to the hearts of liberty lovers: Frederic Bastiat’s The Law, written near the end of his life in 1850 France. This is my third year teaching it to freshmen, and I find it more and more excellent every time I read it. The words and arguments come off the pages like notes and melodies, and it feels like a symphony of ideas.

Natural Law

Its first movement is powerful and audacious, beginning with a blasting fanfare of our natural, God-given rights. From nature we are granted life—physical, intellectual, and moral. Life alone cannot sustain itself, so we must apply the talents and faculties given to us by nature to develop, preserve, and perfect our lives.

The efforts and work we do must be ours; not all can work in the same way at the same capacity for the same purpose. So, we must have the liberty to choose our desired and proper labor. From our labor, this free application of our faculties, we create that which supports and develops our existence. Whether it be food, shelter, tools, music, art… the fruits of our labor, our property, are ours to keep in order to sustain our lives. We hold this triumvirate of rights from our Creator; that is, they exist before and above any man-made institution.

This trumpeting of human dignity is nevertheless accompanied by the strong, ominously beating rhythm of fallen human nature. Our reason is what makes us human, and it is the natural law that clarifies truth and tells us we ought not violate the rights of others. But free will also comprises our human nature and gives us the ability to ignore our reason, to ignore natural law.

We must then protect our rights, but since we must also labor and enjoy our property, it becomes increasingly difficult to do it all. So, we form communities to more easily defend ourselves and voluntarily exchange with one another to provide for ourselves. Over time, these communities become too large for people to just agree on how things should be, and they require written rules to outline what we can and cannot do. Thus, the law is born.

The law, Bastiat says, is force that prevents us from hurting one another. It is collective force because its power (that of self-defense) comes from our own individual right of self-defense. The law is, then, the collective force of self-defense with the purpose of protecting our rights.

The implications of this thesis have the sound of a bow drawn over a somber chord of strings. The law in its true meaning is not a force to compel us to do certain things. It is meant only to arrest our baser nature from acting upon others. Our liberty, the freedom to act upon ourselves or our property as we deem fit, is not license or freedom to act upon others and their property. The law is meant to ensure that our liberty is preserved and our desire to rule over others is prevented. The law does not compel your involvement with others but repels your invasion of others. With the deep clarity of a solo cellist, Bastiat affirms that justice, in terms of man dealing with man in society and government, cannot have its own existence. If it did, then we must actively do something to be just, and if we do not, then the law would be empowered to force our action, to strip us of liberty. The law would, in effect, defeat itself. Justice is the absence of injustice, and the law must create the absence of injustice. It must prevent crimes, not enforce virtue.

It is the perversion of the law, the use of collective force for plunderous ends, that destabilizes society. The stupid greed of cronies and the false philanthropy of coerced fraternity bring about a law that takes what is ours without our consent. Whether it be the methods of protectionism that shield certain people or businesses from the difficulties of life at the expense of others or the idea of using force to enact “charity” among man, our pleas and petitions for justice are ignored. Who are the proponents of a system that advocates for such abuse?

Exploiters of the Law

We then come to the second movement of The Law, filled with unnerving individuals Bastiat calls socialists and ignorant legislators. He takes a considerable amount of time lambasting specific individuals, contemporary and past, whom he identifies as enemies of the law—the people who pervert the law for their own purposes.

The socialist view of man, Bastiat says, is that of an unmolded, inert, passive lump of life that must be formed and organized. Man is devoid of free will and reason, and only through the infallible wisdom of the Übermensch legislator can society hope to achieve greatness. Bastiat brings our attention to the dangers of these men with quiet but tense sounds of tyranny. The socialists desire to establish a dictatorship for themselves, like that of ancient Rome. But instead of the goal of repelling a known and visible foreign invader, they seek to remove human vice and instill virtue as defined by them—a goal, Bastiat reminds us, that is impossible to obtain because of our free will. More than mere Caesars, socialists desire to be gods.

The socialist view of man, Bastiat says, is that of an unmolded, inert, passive lump of life that must be formed and organized. Man is devoid of free will and reason, and only through the infallible wisdom of the Übermensch legislator can society hope to achieve greatness. Bastiat brings our attention to the dangers of these men with quiet but tense sounds of tyranny. The socialists desire to establish a dictatorship for themselves, like that of ancient Rome. But instead of the goal of repelling a known and visible foreign invader, they seek to remove human vice and instill virtue as defined by them—a goal, Bastiat reminds us, that is impossible to obtain because of our free will. More than mere Caesars, socialists desire to be gods.

Our conductor relieves our sense of doom and arrives at the finale, which begins with the soft but firm notion that man, though fallen, is not without hope. Man is capable of great evil, yes, but also of supreme good. It is not by the edicts of dynasties that societies become great but the time and experience of a people that fail, make mistakes, learn, and grow. When people are free, the people are prosperous—in wealth but also in virtue.

Law is justice. Over and over, time again, like the cannons in Tchaikovsky’s overture, Bastiat rings our ears with the sound of “Law is Justice.” Let people have the power to choose poorly so they may then choose wisely! People can be good, and a law that protects the rights of man to be good and free from tyranny creates peace. Let us, he concludes, try liberty.

Written by Stanton Skerjanec for The Generalist ~ September 22, 2018

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE:

Pingback: Mornin’ Coffee: June 14, 2019 | The Federal Observer

Mr Stanton Skerjanec composed this lil’ sonnet of Freddy Bastiat’s ‘The Law’ so beautifully. The first ‘jewel’ he’s presented was “… (OUR) liberty… OUR labor… the fruits of our labor, OUR property… We hold this triumvirate of rights from our Creator;…” (MY emphasis.)

A “triumvirate of rights”.

My, that phrase has a sweet, clear ‘ring’ to it, like Mark Twain’s ‘silver bell sounding Truth’. Just imagine what we could DO with such powerful, versatile ‘tools’ as “a triumvirate of rights”. And to think, that our “certain Rights”, like this triumvirate, endowed upon us by our Creator, are infinate; our Natural Rights ARE, literally… without number.

I see NO reason not to go and DO something, something to begin to try and recipricate, since The Creator has equipped me so well.

(An’ Massa Jeffrey, don’ you go echoin’ ’bout how well endowed YOUSE bees, too, boss!)