Why is it that so many students in the modern American education system say that school is “boring”? Aren’t they learning about the most fascinating aspects of our world? Isn’t part of human nature, as Aristotle teaches, to desire to know?

Why is it that so many students in the modern American education system say that school is “boring”? Aren’t they learning about the most fascinating aspects of our world? Isn’t part of human nature, as Aristotle teaches, to desire to know?

In his brilliant essay “The Loss of the Creature,” the novelist and philosopher Walker Percy offers one answer to this question (and there are many). He describes a peculiarly modern disease: our inability to see.

For example, our experience of a travel destination is so mediated through expectations (largely formed by how the place has been marketed to us, what others have said or thought) that we are not really “present” in the place. We are comparing it to what we expect it to be, to what we think it ought to be. We are going through the motions. We cease to be capable of wonder.

Percy uses the example of the Grand Canyon. He says it’s possible for a tourist to go there, to take the tour, to look at it according to the set rules and customs for looking at it, and to return home without actually having seen it in the same way that, for example, its initial discoverer, Garcia Lopez de Cárdenas, truly saw it – with surprise, wonder, admiration.

Percy asks, “Why is it almost impossible to gaze directly at the Grand Canyon under these circumstances and see it for what it is – as one picks up a strange object from one’s back yard and gazes directly at it?”

And his answer: “It is almost impossible because the Grand Canyon, the thing as it is, has been appropriated by the symbolic complex which has already been formed in the sightseer’s mind.”

The tourist can’t help comparing the canyon with the photos and videos he’s seen of it, all the while suffering anxiety that it won’t “live up” to those artificial standards, that he won’t “get out of it” what the other millions of tourists claim to have gotten out of it. The experience of the canyon lacks reality and authenticity.

Percy suggests that, to really see the canyon, the tourist would need to discard the “packaging,” go off the beaten track, approach the canyon through the wilderness, or, alternatively, to have some other reason for being in the area, making the canyon merely a dramatic background, which, as such, would be capable of surprising and enchanting the viewer by its unexpected presence.

Percy then applies these ideas to education. He suggests that the educational apparatus, rather than transmitting the experience of true education, may obscure it:

“The new textbook, the type, the smell of the page, the classroom, the aluminum windows and the winter sky, the personality of Miss Hawkins – these media which are supposed to transmit the sonnet [in English class] may only succeed in transmitting themselves.”

Thus is education defeated, for the real purpose of true education is to lead the student into the wonder of the real. Percy explains the difference between experiences mitigated by “packaging” and experiences that are raw and direct:

“A young Falkland Islander walking along a beach and spying a dead dogfish and going to work on it with his jackknife has, in a fashion wholly unprovided in modern educational theory, a great advantage over the Scarsdale high-school pupil who finds the dogfish on his laboratory desk. Similarly, the citizen of Huxley’s Brave New World who stumbles across a volume of Shakespeare in some vine-grown ruins and squats on a potsherd to read it is in a fairer way of getting at a sonnet than the Harvard sophomore taking English Poetry II.”

The Falklander or the man in the ruins has simply stumbled upon something real, in its natural environment. When a reality is placed into an artificial context, by contrast, the thing studied may become invisible, overcome and erased by the scientific, compartmentalized manner in which it is presented.

Percy’s example of the dogfish demonstrates this: In the lab, the fish ceases to be a marvel of creation and becomes, instead, that dry, dead, sterile, stultified, scientific thing: a specimen. “The phrase specimen of expresses in the most succinct way imaginable the radical character of the loss of being which has occurred,” Percy argues. The fish is no longer a mystery. It is merely matter to be methodically mangled and explained away by theory.

Percy’s example of the dogfish demonstrates this: In the lab, the fish ceases to be a marvel of creation and becomes, instead, that dry, dead, sterile, stultified, scientific thing: a specimen. “The phrase specimen of expresses in the most succinct way imaginable the radical character of the loss of being which has occurred,” Percy argues. The fish is no longer a mystery. It is merely matter to be methodically mangled and explained away by theory.

Here’s another view of the problem: In Hard Times by Charles Dickens, a harsh schoolmaster demands that a girl in his class, Sissy Jupe, explain to him what a horse is. Sissy has lots of experience with real horses, but she doesn’t know the scientific definition that the master is looking for. The master calls on another student, Bitzer, who automatically responds:

“Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.”

Of course, it is Sissy who has a real knowledge of horses, who has actually seen them and loved them, not Bitzer. She knows the essence of the horse. Bitzer is just as ignorant of a horse after learning the above definition as he was before – perhaps more so. He has seen it only as a specimen, not a concrete, living being. He is probably bored by horses.

No wonder students are bored if they have lost the ability to truly see the thing they are studying. Like the tourists, they are just going through the motions, doing the things students are supposed to do. They are not awake to the beauty and surprise of the being that they are encountering.

Percy’s recommendation for educators, then, is represented by this scenario: Once in a while, the biology student should walk into class and find a Shakespearean sonnet on the dissecting table, and, once in a while, the English student should walk into class and find a dogfish on the table. The startled students would, perhaps, see the thing for the first time and be truly able to learn about it.

Percy is not arguing that teachers must become ever-better performers and entertainers, like late night talk show hosts, resorting to a circus of novelties, cute tricks, sleight-of-hand, and gimmicky visuals. Trying to compete with video games, TV, and social media at mere overstimulation of the senses is neither possible nor desirable.

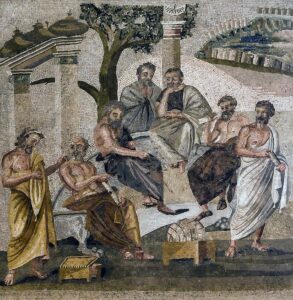

But perhaps Percy would say that we should return to a purer, less industrialized, less formulaic kind of learning. One thinks of Plato’s Academy. The word academy did not then carry the connotations and baggage it does now – rather, it was named after the grove of trees, Akadēmeia (which was in turn named for a Greek hero), where Plato would speak to his students about things that matter. These students were not thinking about grades, about the footnotes in their textbooks (there were no textbooks), about when the next bell would ring. They were simply a group of friends listening to a wise older man and wondering about the universe.

But perhaps Percy would say that we should return to a purer, less industrialized, less formulaic kind of learning. One thinks of Plato’s Academy. The word academy did not then carry the connotations and baggage it does now – rather, it was named after the grove of trees, Akadēmeia (which was in turn named for a Greek hero), where Plato would speak to his students about things that matter. These students were not thinking about grades, about the footnotes in their textbooks (there were no textbooks), about when the next bell would ring. They were simply a group of friends listening to a wise older man and wondering about the universe.

What exactly this would look like in a modern context is a question I continue to struggle with as a teacher and may be the subject of future reflections. For now, I wish only to highlight the wisdom and accuracy of Percy’s diagnosis. We must learn how to see again, or there’s no hope for education.

Written by Walker Larson for Intellectual Takeout ~ April 15, 2024