Prestigious study shows average American schoolchild slipped SIX MONTHS behind with math – with students in poorest areas now two-and-a-half years behind

The average American child fell behind in math by six months due to COVID school closures, with students in the nation’s poorest areas behind two-and-a-half years.

The average American child fell behind in math by six months due to COVID school closures, with students in the nation’s poorest areas behind two-and-a-half years.

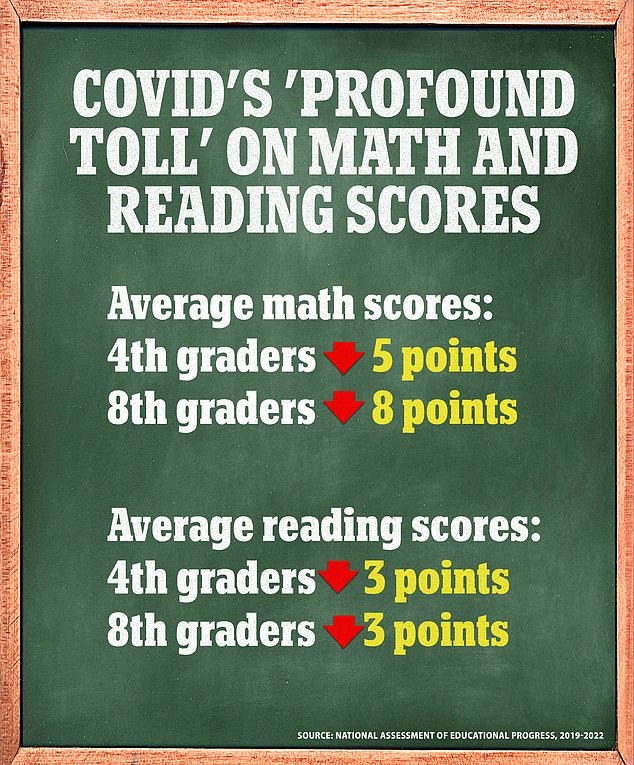

According to the Education Recovery Scorecard, which gathered a district-by-district analysis of test scores, the average student lost more than half a school year of learning in math and nearly a quarter of a school year in reading.

The report said the pandemic devastated children’s well-being, not just by closing their schools, but also by taking away their parents’ jobs, sickening their families and teachers, and adding chaos and fear to their daily lives.

‘When you have a massive crisis, the worst effects end up being felt by the people with the least resources,’ said Stanford education professor Sean Reardon, who compiled and analyzed the data along with Harvard economist Thomas Kane.

According to their research, students in Hopewell, Virginia, which is predominantly low-income, lost about 2.29 years in math, while in Rochester, New Hampshire, where about half the student body lives in poverty, kids are behind two years in reading.

Meanwhile, in Memphis, where 80 percent of students live in poverty, students are nearly behind a year in both math and reading, with researchers noting that black children were faring worse.

The data provides the most comprehensive look yet at how much schoolchildren have fallen behind academically, with the federal government’s own report card indicating that math and reading scores have reached record lows.

Online learning played a major role, but students lost significant ground even where they returned quickly to schoolhouses, especially in math scores in low-income communities.

Reading and math scores are one of the only aspects of children’s development reliably measured nationwide.

‘Test scores aren’t the only thing, or the most important thing,’ Reardon said. ‘But they serve as an indicator for how kids are doing.’

And kids aren’t doing well, especially those who were at highest risk before the pandemic. The data show many children need significant intervention, and advocates and researchers say the US isn’t doing enough.

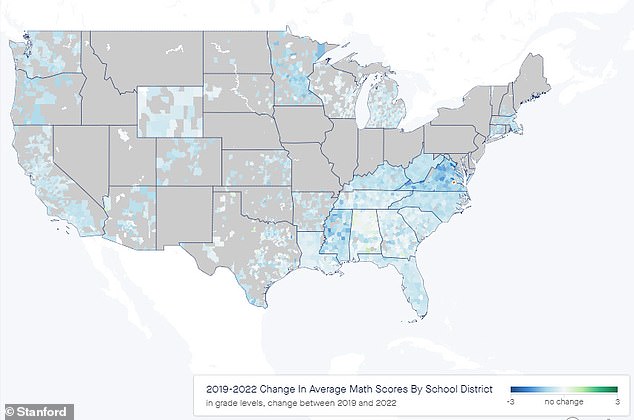

Together, Reardon and Kane created a map showing how many years of learning the average student in each district has lost since 2019.

In some districts, students lost more than two years of math learning, according to Reardon and Kane’s data. Hopewell, Virginia, a school system of 4,000 students who are mostly low-income and 60 percent Black, showed an average loss of 2.29 years of school.

‘This is not anywhere near what we wanted to see,’ Deputy Superintendent Jay McClain said.

The district began offering in-person learning in March 2021, but three-quarters of students remained home. ‘There was so much fear of the effects of COVID,’ he said. ‘Families here were just hunkered down.’

When schools resumed in the fall, the virus swept through Hopewell, and half of all students stayed home either sick or in quarantine, McClain said. A full 40 percent of students were chronically absent, meaning they missed 18 days or more.

Some educators have objected to the very idea of measuring learning loss after a crisis that has killed more than 1 million Americans.

The latest report adds to federal data revealing students are severely behind on their education due to the pandemic. Pictured: Students working in a classroom at Beecher Hills Elementary School in Atlanta in August

The pandemic brought other challenges unrelated to remote learning.

In Rochester, New Hampshire, students lost nearly two years in reading even though schools offered in-person learning most of the 2020-2021 school year. It was the largest literacy decline among all the districts in the analysis.

The 4,000-student district, where most are white and nearly half live in poverty, had to close schools in November 2020 when too few teachers could report for work, Superintendent Kyle Repucci said.

Students studied online until March 2021, and when schools reopened, many chose to stay with remote learning, Repucci said.

Charles Lampkin (above), a pastor and father in Memphis, said he’s seen the effects on his own sons’ who were struggling with their reading lessons tailored to their 5th grade level. He is now tutoring children in the city, where 80 percent of the students are considered lower-income, in order to help overcome the pandemic’s effects

‘Students here were exposed to things they should never have been exposed to until much later,’ Repucci said. ‘Death. Severe illness. Working to feed their families.’

In Memphis, Tennessee, where nearly 80 percent of students are poor, students lost the equivalent of 70 percent of a school year in reading and more than a year in math, according to the analysis.

The district’s black students lost a year-and-one-third in math and two-thirds of a year in reading.

For church pastor Charles Lampkin, who is black, it was the effects on his sons’ reading that grabbed his attention.

He was studying the Bible with them one night this fall when he noticed his sixth and seventh graders were struggling with their ‘junior’ Bible editions written for a fifth grade reading level. ‘They couldn’t get through it,’ Lampkin said.

Lampkin blames the year and a half his sons were away from school buildings from March 2020 until the fall of 2021.

‘They weren’t engaged at all. It was all tomfoolery,’ he said.

The local school district this year set aside an hour every day for intervention, when struggling students can receive small-group tutoring, said Memphis-Shelby County Public Schools spokesperson Cathryn Stout.

Students also receive tutoring help before and after school, and some campuses have started offering Saturday classes to help students catch up.

Lampkin said his sons have not been offered the extra help.

The amount of learning that students lost – or gained, in rare cases – over the last three years varied widely.

Poverty and time spent in remote learning affected learning loss, and learning losses were greater in districts that remained online longer, according to Kane and Reardon’s analysis. But neither was a perfect predictor of declines in reading and math.

In Los Angeles, school leaders shuttered classrooms for the entire 2020-2021 academic year, yet students held their ground in reading.

It´s hard to tell what explains the vastly different outcomes in some states. In California, where students on average stayed steady or only marginally declined, it could suggest that educators there were better at teaching over Zoom or the state made effective investments in technology, Reardon said.

But the differences could also be explained by what happened outside of school.

‘I think a lot more of the variation has to do with things that were outside of a school´s control,’ Reardon said.

Reardon and Kane’s project, the Education Recovery Scorecard, compared results from a test known as the ‘nation’s report card’ with local standardized test scores from 29 states and Washington, D.C.

Now, the onus is on America’s adults to work toward kids’ recovery.

For the federal government and individual states, advocates hope the recent releases of test data could inspire more urgency to direct funding to the students who suffered the largest setbacks, whether it’s academic or other support.

For the federal government and individual states, advocates hope the recent releases of test data could inspire more urgency to direct funding to the students who suffered the largest setbacks, whether it’s academic or other support.

School systems are still spending the nearly $190 billion in federal relief money allocated for recovery, a sum experts have said fails to address the extent of learning loss in schools.

Nearly 70 percent of students live in districts where federal relief money is likely inadequate to address the magnitude of their learning loss, according to Kane and Reardon´s analysis.

The implications for kids’ futures are alarming: Lower test scores are predictors of lower wages, plus higher rates of incarceration and teen pregnancy, Kane said.

It doesn’t take Harvard research to convince parents whose children are struggling to read or learn algebra that something needs to be done.

At his church in Memphis, Lampkin started his own tutoring program three nights a week.

Adults from his congregation, some of them teachers, help around 50 students with their homework, reinforcing skills and teaching new ones.

‘We shouldn’t have had to do this,’ Lampkin said. ‘But sometimes you have to lead by example.’

Written by Ronny Reyes for The Daily Mail ~ October 29, 2022

Keep them at home…