They warned of an exodus to come!

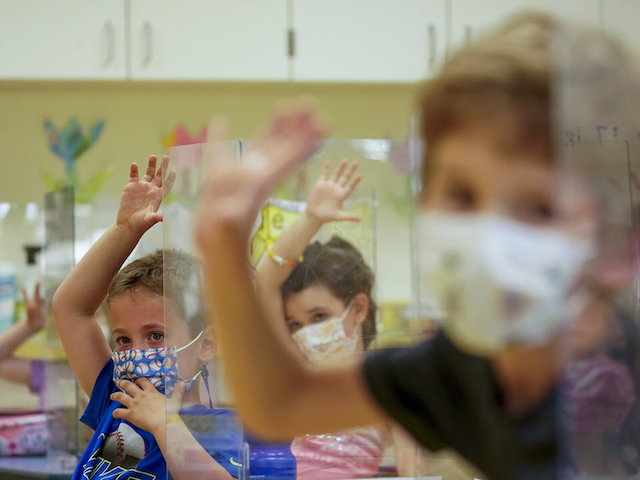

After a rough couple of years, teachers are feeling the pressure. Mary Altaffer/AP

School is out, but teacher stress and burnout is still in session.

Last December, we spoke to teachers about the challenges of educating during a pandemic and their hopes for the coming year.

While many of them had initially thought a return to the classroom after remote learning would make things easier, others realized a new set of challenges had arisen.

“The teachers are just feeling overwhelmed, and they’re breaking down underneath it,” Michael Reinholdt, a teacher coach from Davenport, Iowa, said at the time. “I find people crying in the bathroom.”

Back then, the first omicron COVID wave was sweeping the country and schools were trying their hardest to return to normal after two years of closures, illness and disruption.

Since then, the question of basic safety has also come back into sharp focus after the Uvalde, Texas school shooting last month.

So, how are teachers reflecting on the year that was and the future ahead?

We caught up with Reinholdt; Suzen Polk-Hoffses, a pre-K teacher in Milbridge, Maine; and Tiki Boyea-Logan, a 4th grade teacher in Rowlett, Texas, to hear their thoughts.

Bulletproof backpacks and a pandemic

“Honestly, I feel like we’ve been thrown an inner tube,” Reinholdt said, reflecting on his December assessment that teachers were drowning. “So we’re floating, but we’re only halfway back to the ship. We just have a lot of work to do.”

With the recent shooting in her own state, Boyea-Logan said the return to normalcy seemed increasingly unattainable.

“We’re always kind of paying attention and [thinking], ‘You see something, say something,’ but this current shooting brought it all back,” she said.

The shooting at Robb Elementary School has left many feeling unsafe now that students are back to the classroom

In the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, Boyea-Logan’s husband bought her a bulletproof backpack, which she still brings to school to this day.

“Just thinking about saying that in an elementary school setting is just so ridiculous,” she said. “But I mean, that’s just what we’re dealing with right now.”

Boyea-Logan teaches fourth grade, and has witnessed firsthand how disruptive the pandemic has been to the development of her students.

“I feel like at the beginning of the school year, I basically got second graders, because that’s the point where they were in school full time,” she said.

“Though you’re a fourth grade teacher, you’re teaching kids who are emotionally at the second grade level. And academically, we’re back to working miracles, like, ‘Hey, we need to get these kids caught up, we need to fill these gaps.'”

Beyond academic development, teachers are also reporting serious concerns around mental health.

Polk-Hoffses said that although her pre-K students were coming to her “fresh” at a young age, she had witnessed the concern among her colleagues.

“They’re very worried about the students that they had this year, because they saw a lot of depression. Someone even brought up cutting, they were afraid that a student would begin cutting again,” Polk-Hoffses said.

“Students were learning in isolation, then they came back, and they’re overwhelmed, and they’ve experienced a trauma. And unfortunately, all schools aren’t equipped to deal with the trauma that the students have experienced during the pandemic.”

Teachers could be driven to quit

While Boyea-Logan and Polk-Hoffses remain passionate about their vocation, both expressed concern about the sustainability of their work conditions.

“I just worry about our young educators who haven’t been in the field as long as I have,” Polk-Hoffses said. “I’ve been in the field of teaching for 21 years, I still feel strong and resilient. And I just want to let the young educators know, please find support somewhere within your school, your family, please don’t leave the profession.”

This is one thing Reinholdt, Polk-Hoffses and Boyea-Logan are all warning of: A possible exodus of teachers in the summer.

“My fear is that during the summer, they’ll just say, ‘I just can’t do this anymore, because it was just too hard,'” Polk-Hoffses said.

Teachers are warning of mental health challenges raised by the pandemic.

Brynn Anderson/AP

Boyea-Logan understands that thinking firsthand. For her, the question isn’t whether she wants to go on, but whether she can.

“It’s just way too much has been put on our shoulders,” she said. “I feel like they expect us to juggle 18 different balls and hop on one foot while saying our ABCs backwards. I mean, that’s how it feels. And I feel like it doesn’t seem like there’s any relief in sight.”

Boyea-Logan said she hoped legislators and the upper management of school districts look at the data of teachers leaving.

“And I hope they really look at that and really ask these teachers, and really pay attention to their answers, about why they’re leaving, [asking], ‘What can we do to fix this?'”

“Because if they don’t, they’re just gonna be hemorrhaging really good teachers for the foreseeable future.”

Reinholdt said teachers were naturally “eternal optimists” in order to get the job done, but would reach their limit, while Polk-Hoffses worried of an exodus and asked one thing to anyone reading this:

“Understand how you can help support your local schools. You need to, because these children are our future. We need them educated. Help us educate them, please.”

Written by Manuela López Restrepo & Ailsa Chang for NPR – June 18, 2022

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE: