‘Take me out to the Ballgame…’ ~ when it was still a ‘sport.’

An irrepressible son of New York City, Ford joined the pantheon of baseball legends who dominated the 1950s and ’60s.

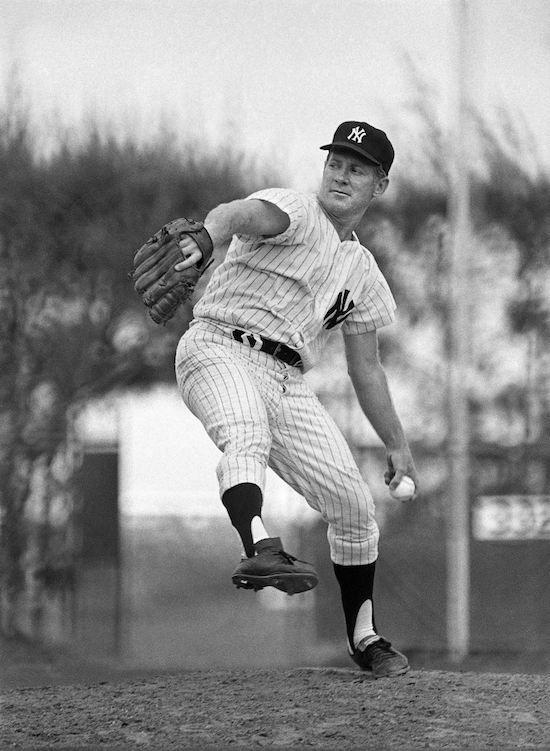

Whitey Ford pitching batting practice at the Yankees’ spring training camp in 1971, four years after retiring. A Yankee for his entire career, he won 236 games, the most of any Yankee, and had a career winning percentage of .690. Ernie Sisto/The New York Times

Whitey Ford, the Yankees’ Hall of Fame left-hander who was celebrated as the Chairman of the Board for his stylish pitching and big-game brilliance on the ball clubs that dominated baseball in the 1950s and early ’60s, died on Thursday night at his home in Lake Success, N.Y., on Long Island. He was 91. The Yankees announced his death.

Pitching for 11 pennant-winners and six World Series champions, Ford won 236 games, the most of any Yankee, and had a career winning percentage of .690, the best among pitchers with 200 or more victories in the 20th century.

At his death, Ford was the second-oldest surviving Hall of Famer, behind the former Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda, who is 93. His death came six days after that of his fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson of the St. Louis Cardinals.

He was a scrappy, rambunctious, fair-haired son of New York City — hence the nickname — and through the decades a beloved one, as loyal to Yankee pinstripes as his most die-hard fans. “I’ve been a Yankee fan since I was 5 years old,” Ford said at his Hall of Fame induction at Cooperstown, N.Y., in 1974.

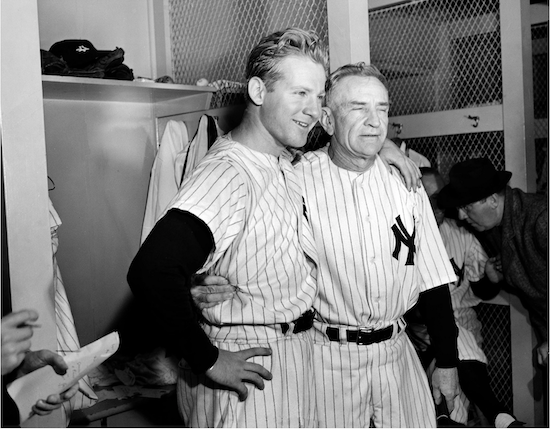

Ford and the Yankees’ manager, Casey Stengel, in 1950, after the Yankees won a fourth straight game against the Phillies to take the World Series. Associated Press

He was among the biggest names on Yankee teams featuring Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Roger Maris and his 1950s pitching mates Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi and Eddie Lopat. He survived all of them. And he joined Lou Gehrig, DiMaggio, Mantle and Rizzuto among the revered figures who spent their entire playing careers with the Yankees. The team retired his No. 16 and mounted his plaque beside theirs in Monument Park at Yankee Stadium.

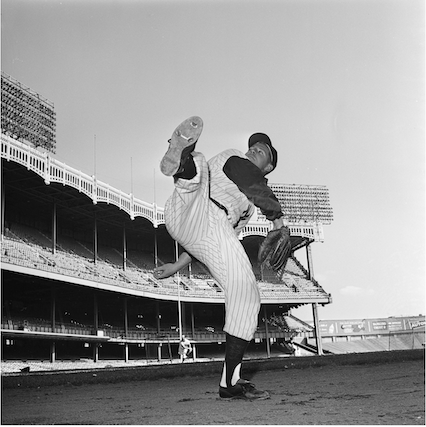

Ford had the competitive advantage of pitching for dauntingly good teams. But his prowess was never seriously questioned as he compiled an impressive 2.75 earned run average in 3,170 innings.

“He could throw any pitch, any time, for a strike,” Brooks Robinson, the Baltimore Orioles’ Hall of Famer, was quoted as saying by Fay Vincent, the former baseball commissioner, in the oral history “We Would Have Played for Nothing” (2008). “He had great players behind him, but Whitey Ford was the master.”

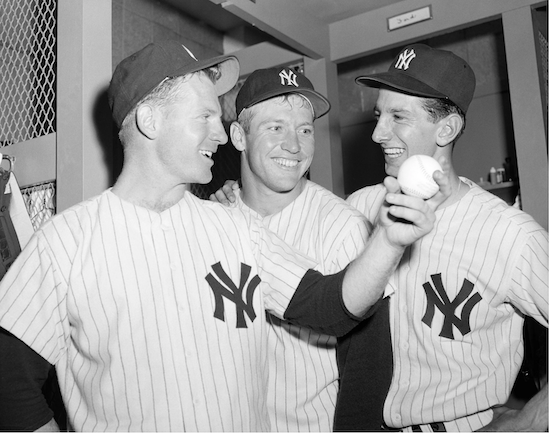

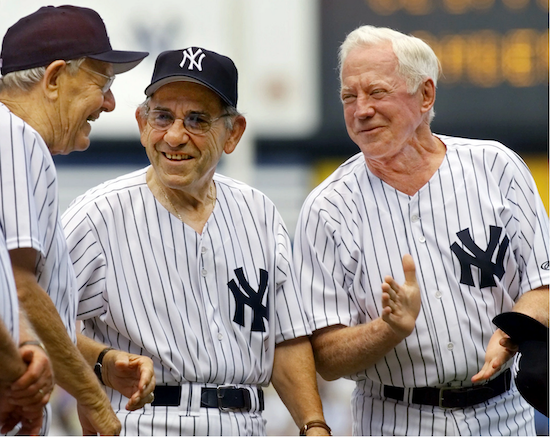

The Three Musketeers

At 5 feet 10 inches and 180 pounds, Ford seldom overpowered batters. But in his 16 seasons he mastered them with an assortment of pitches thrown with varying speeds and arm motions and delivered just where he wanted them. “If it takes 27 outs to win, who’s going to get them out more ways than Mr. Ford?” the longtime Yankee manager Casey Stengel once said.

Methodical on the mound, Ford was irrepressible off it. He joined with Mantle and Billy Martin for late nights on the town, inspiring Stengel to call them the Three Musketeers. Mantle, too, entered the Hall of Fame in 1974, and at the induction ceremony he was asked about the chemistry behind the friendship between him, the country boy from Oklahoma, and Ford, who grew up on the streets of Queens. “We both liked Scotch,” he said.

“In those early years it was three of us — me, Whitey and Billy Martin,” Mantle said, adding, “They were both brash, outspoken guys, and I could stay in the background.”

With the passing of DiMaggio and Mantle, Old-Timers’ Day at Yankee Stadium became very much the Whitey and Yogi show. Ford and Berra, his catcher and baseball’s philosopher, were the celebrity elders of the hour. (Berra died in 2015 at 90.)

Ford, left, and his teammates Mickey Mantle, center, and Billy Martin were known for their late nights on the town, which earned them the nickname the Three Musketeers. Bettmann, via Corbis

It was in retirement, too, that Ford acknowledged what had been widely suspected: He sometimes doctored the baseball. He said he created “mud” balls by mixing saliva and dirt; used a concoction of baby oil, turpentine and resin to make his fingers sticky; and had a ring made with a specially attached rasp to cut baseballs, all to make a pitch break unexpectedly and produce strikeouts or ground balls — and to help win championships.

Ford held a number of still-standing World Series records, among them 33⅔ consecutive innings of scoreless pitching. He was savvy from the start, a puzzle that batters struggled to solve.

Walt Dropo, the slugging Boston Red Sox first baseman who beat Ford out for Rookie of the Year honors, remembered facing Ford that first season. “Right away, I could see this guy was going to be trouble,” Dropo recalled in “Bombers” (2002), edited by Richard Lally. “He was like a master chess player who used his brain to take the bat right out of my hands. You’d start thinking along with him, and then Whitey had you because he never started you off with the same pitch in any one sequence.

“He could start you with a fastball inside, a curveball outside, then reverse that, or even start you with a changeup. He played games with everybody, every hitter I ever talked to. He made them hit his pitch, and it was usually something they didn’t like.”

A Hometown Boy

Edward Charles Ford was born on Oct. 21, 1928, on the East Side of Manhattan, the only child of Jim and Edna Ford. His father worked for Con Edison and played on its semipro baseball team, and his mother was a bookkeeper at an A&P grocery.

He grew up in the Astoria section of Queens, idolizing Joe DiMaggio. He played first base for Manhattan High School of Aviation Trades, which he attended because his neighborhood high school, William Cullen Bryant, did not have a baseball team.

In April 1946, his senior year, he attended a tryout at Yankee Stadium. The Yankee scout Paul Krichell felt that Ford couldn’t hit well enough to be a first baseman, but noticed that he had a strong arm. After pitching a few innings near the end of his high school season, Ford turned in an outstanding summer as a pitcher for the 34th Avenue Boys, a Queens sandlot team sponsored by a beer garden, and in October 1946 the Yankees gave him a $7,000 bonus as a pitching prospect.

After three and a half years in the minors, Ford made his Yankee debut on July 1, 1950. Slim and blond, he was Eddie Ford back then. Lefty Gomez, the former Yankee pitcher who managed in the team’s farm system, had called him Whitey, but the name hadn’t stuck yet.

Tutored by Jim Turner, the pitching coach, and by Lopat, Ford won nine straight games before he was beaten on a home run by the Philadelphia Athletics’ Sam Chapman.

Ford with Yogi Berra outside Yankee Stadium in 1956. Ernie Sisto/The New York Times

After the Yankees won the first three games of the 1950 World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies’ Whiz Kids, Stengel gave Ford a start at Yankee Stadium. He was within one out of a shutout when Gene Woodling, the Yankee left fielder, dropped a fly ball, allowing two runs to score. Stengel eventually took Ford out of the game, to the displeasure of Yankee fans, and Reynolds finished off a 5-2 Yankee victory and a World Series sweep.

Ford missed the 1951 and 1952 seasons while in the Army, but returned with an 18-6 season in 1953. As he remembered it, Yankee catcher Elston Howard gave him the nickname Chairman of the Board around the mid-’50s.

Ford kept rolling along, winning 53 games from 1954 to 1956.

Then came an infamous night in Yankee lore. In May 1957, Ford and Mantle joined with a few teammates to celebrate Martin’s 29th birthday at the Copacabana nightclub. A patron wound up on the floor with a broken nose and accused Hank Bauer, the Yankees’ strapping right fielder, of decking him. Bauer denied it, and no charges were filed, but the Yankees fined all the players who were there for the embarrassing headline-making episode. It was never clear who clobbered the customer, and Berra famously explained, “Nobody did nuthin’ to nobody.” But Martin was soon banished to the lowly Kansas City Athletics.

In April 1958, to mark the start of another baseball season, Ford did a star turn with Berra, Mantle and first baseman Bill Skowron on Ed Sullivan’s popular CBS variety show with a rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” They were accompanied by Jack Norworth, who wrote the lyrics in 1908.

The Yankees concluded the season by defeating the Milwaukee Braves in the World Series.

A World Series Maven

The winning ways continued for Ford into the early 1960s.

He was at his best in the World Series, his records including most victories (10) and most strikeouts (94) along with his 33⅔ straight scoreless innings.

He threw two shutouts against the Pirates in the 1960 World Series, though his pitching was overshadowed by Bill Mazeroski’s Series-winning home run for Pittsburgh in Game 7. He pitched another shutout in Game 1 of the 1961 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds and pitched five scoreless innings in Game 4 before a reliever came in. The Yankees won that Series in five games, with Ford’s total of 32 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play eclipsing the record of 29⅔ innings set by Babe Ruth for the Boston Red Sox in 1916 and 1918.

Ralph Houk, who replaced Stengel as the Yankees’ manager in 1961, used Ford more frequently than Stengel had, and Johnny Sain, who became the pitching coach that year, added to Ford’s repertoire by teaching him to throw a slider. Ford won 14 consecutive games, posted a 25-4 record and captured the Cy Young Award as baseball’s best pitcher.

In the 1961 All-Star Game at the San Francisco Giants’ Candlestick Park, Ford delivered what might have been his most confounding single pitch.

Ford “could start you with a fastball inside, a curveball outside, then reverse that, or even start you with a changeup,” said Walt Dropo, the slugging Boston Red Sox first baseman.

Ford “could start you with a fastball inside, a curveball outside, then reverse that, or even start you with a changeup,” said Walt Dropo, the slugging Boston Red Sox first baseman.Credit…Ernie Sisto/The New York Times

Ford “could start you with a fastball inside, a curveball outside, then reverse that, or even start you with a changeup,” said Walt Dropo, the slugging Boston Red Sox first baseman. Ernie Sisto/The New York Times

Horace Stoneham, the Giants’ owner, bet Ford that he couldn’t get Willie Mays out, as Ford told it in “Whitey and Mickey” (1977), a joint Ford-Mantle memoir written with Joseph Durso of The New York Times. A few hundred dollars were at stake.

Ford recalled that when he faced Mays in the first inning, “I threw Willie the biggest spitball you ever saw” and “it snapped the hell out of sight, and the umpire shot up his right hand for strike three.”

Ford extended his World Series scoreless string to 33⅔ innings before the Giants’ Jose Pagan put down a bunt single that scored Mays in the second inning of the 1962 World Series opener, at San Francisco. But Ford won that game, his final World Series triumph.

He was 24-7 in 1963, his last outstanding season.

Ford added pitching-coach duties in 1964, when Berra became the manager and Houk was promoted to general manager. But pitching against the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series opener, he developed numbness in his left hand and departed in the sixth inning.

He underwent surgery in November for a blocked artery, but that procedure was a temporary solution, and he continued to experience circulatory problems pitching in cool weather the next season. He lost his pitching-coach job when Johnny Keane, formerly the St. Louis Cardinals’ manager, took over from Berra.

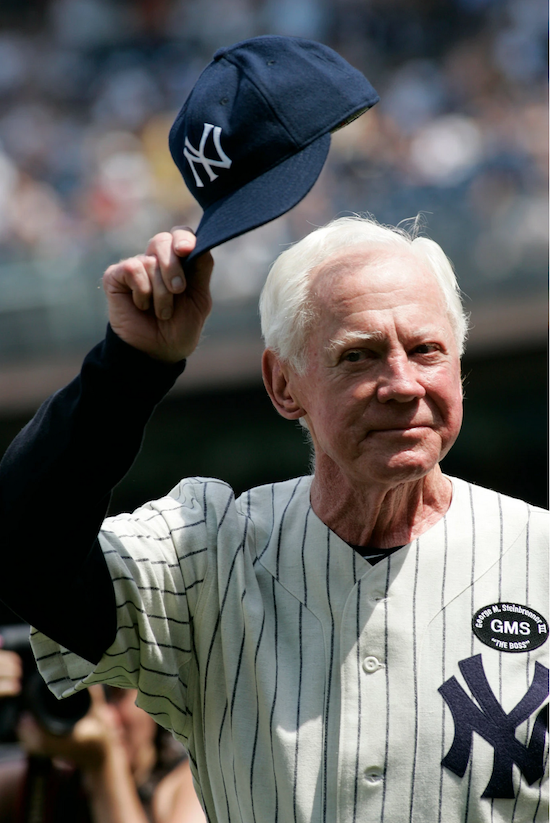

Ralph Houk, left, the former Yankees manager, with Berra and Ford at the 2001 Old-Timers’ Day at Yankee Stadium. With the passing of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle, such days became very much the Whitey and Yogi show. Reuters

Ford had a 16-13 record in 1965, but he was plagued by arm problems in 1966. He had a 2-5 record when he underwent bypass surgery in August to provide a permanent cure for his circulatory problem. But he also had a bad elbow, and he retired in May 1967 after going 2-4.

Ford had an earned run average below 3.00 in 11 separate seasons and pitched 45 shutouts. He was an eight-time All-Star and posted the American League’s lowest earned run average in 1956 and 1958. He led the league in victories three times (1955, 1961 and 1963), and he had the best winning percentage three times (1956, 1961 and 1963).

He had a career record of 236-106 with a 2.75 earned run average.

Ford’s survivors include his wife, Joan (Foran) Ford; their son Eddie; their daughter, Sally Ann Clancy; and grandchildren. Another son, Tommy, died in 1999.

Ford at the 2010 Yankee Old-Timers’ Day. Uli Seit for The New York Times

After his pitching days, Ford served briefly as the Yankees’ first-base coach and again as pitching coach. The Yankees retired his No. 16 in 1974, shortly before he was inducted into the Hall of Fame. He appeared at Yankee spring training camps after that as a pitching instructor.

Ford was on hand in September 2008 when the Yankees played their final game at the old Stadium. He joined with Don Larsen, famous for pitching a perfect game in the World Series, in scooping dirt from the pitchers’ mound in a pre-game ceremony and then joined with Berra to reminisce with the ESPN broadcasters Jon Miller and Joe Morgan. (Larsen died in January at 90.)

Ford and Berra reprised their cameos as the favorite old-time Yankees when they helped Manager Joe Girardi distribute World Series championship rings to Yankee players at the team’s 2010 home opener.

But the biggest day of the retirement years had come on Aug. 20, 2000, when it was Whitey Ford Day at Yankee Stadium. Ford’s No. 16 was imprinted near the first and third-base foul lines, and former teammates paid tribute.

“I’ve been a Yankee for 53 years,” he said then, “and I’ll be a Yankee forever.”

Written by Richard Goldstein for The New York Times ~ October 9, 2020