THE WHITE HOUSE,

WASHINGTON, D.C.

January 16, 1907

To the HON. Hilary A. Herbert, Chairman,

Chief Justice Seth Shepherd, General Marcus J. Wright,

Judge Charles B. Howry, Mr. William A. Gordon,

Mr. Thomas Nelson Page, President Edwin Alderman,

Mr. Joseph Wilmer, and others of the Committee of Arrangement for the Celebration of the Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of General Robert E. Lee.

Gentlemen:

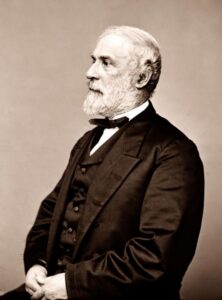

I regret that it is not in my power to be with you at your celebration. I join with you in honoring the life and career of that great soldier and high-minded citizen whose fame is now a matter of pride to all our countrymen. Terrible though the destruction of the Civil War was, awful though it was that such a conflict should occur between brothers, it is yet a matter for gratitude on the part of all Americans that this, alone among contests of like magnitude, should have left to both sides as a priceless heritage the memory of the mighty men and the glorious deeds that the iron days brought forth. The courage and steadfast endurance, the lofty fealty to the right as it was given to each man to see the right, whether he wore the gray or whether he wore the blue, now make the memories of the valiant feats, alike of those who served under Grant and of those who served under Lee, precious to all good Americans. General Lee has left us the memory, not merely of his extraordinary skill as a general, his dauntless courage and high leadership in campaign and battle, but also of that serene greatness of soul characteristic of those who most readily recognize the obligations of civic duty.

I regret that it is not in my power to be with you at your celebration. I join with you in honoring the life and career of that great soldier and high-minded citizen whose fame is now a matter of pride to all our countrymen. Terrible though the destruction of the Civil War was, awful though it was that such a conflict should occur between brothers, it is yet a matter for gratitude on the part of all Americans that this, alone among contests of like magnitude, should have left to both sides as a priceless heritage the memory of the mighty men and the glorious deeds that the iron days brought forth. The courage and steadfast endurance, the lofty fealty to the right as it was given to each man to see the right, whether he wore the gray or whether he wore the blue, now make the memories of the valiant feats, alike of those who served under Grant and of those who served under Lee, precious to all good Americans. General Lee has left us the memory, not merely of his extraordinary skill as a general, his dauntless courage and high leadership in campaign and battle, but also of that serene greatness of soul characteristic of those who most readily recognize the obligations of civic duty.

Once the war was over he instantly under took the task of healing and binding up the wounds of his countrymen, in the true spirit of those who feel malice toward none and charity toward all; in that spirit which from the throes of the Civil War brought forth the real and indissoluble Union of to-day. It was eminently fitting that this great man, this war-worn veteran of a mighty struggle, who, at its close, simply and quietly undertook his duty as a plain, every-day citizen, bent only upon helping his people in the paths of peace and tranquillity, should turn his attention toward educational work; toward bringing up in fit fashion the younger generation, the sons of those who had proved their faith by their endeavor in the heroic days.

There is no need to dwell on General Lee s record as a soldier. The son of Light Horse Harry Lee of the Revolution, he came naturally by his aptitude for arms and command. His campaigns put him in the foremost rank of the great captains of all time. But his signal valor and address in war are no more remarkable than the spirit in which he turned to the work of peace once the war was over. The circumstances were such that most men, even of high character, felt bitter and vindictive or depressed and spiritless, but General Lee s heroic temper was not warped nor his great soul cast down. He stood that hardest of all strains, the strain of bearing himself well through the gray evening of failure; and therefore out of what seemed failure he helped to build the wonderful and mighty triumph of our national life, in which all his countrymen, North and South, share. Immediately after the close of hostilities he announced, with a clear sightedness which at that time few indeed of any section possessed, that the interests of the Southern States were the same as those of the United States ; that the prosperity of the South would rise or fall with the welfare of the whole country; and that the duty of its citizens appeared too plain to admit of doubt. He urged that all should unite in honest effort to obliterate the effects of war and restore the blessings of peace; that they should remain in the country, strive for harmony and good feeling, and devote their abilities to the interests of their people and the healing of dissensions. To every one who applied to him this was the advice he gave.

Although absolutely without means, he refused all offers of pecuniary aid, and all positions of emolument, although many such, at a high salary, were offered him. He declined to go abroad, saying that he sought only “a place to earn honest bread while engaged in some useful work.” This statement brought him the offer of the presidency of Washington College, a little institution in Lexington, Va., which had grown out of a modest foundation known as Liberty Hall Academy. Washington had endowed this academy with one hundred shares of stock that had been given to him by the State of Virginia, which he had accepted only on condition that he might with them endow some educational institution.

To the institution which Washington helped to found in such a spirit, Lee, in the same fine spirit, gave his services. He accepted the position of president at a salary of $1,500 a year, in order, as he stated, that he might do some good to the youth of the South. He applied himself to his new work with the same singleness of mind which he had shown in leading the Army of Northern Virginia. All the time by word and deed he was striving for the restoration of real peace, of real harmony, never uttering a word of bitterness nor allowing a word of bitterness uttered in his presence to go unchecked. From the close of the war to the time of his death all his great powers were devoted to two objects: to the reconciliation of all his countrymen with one another, and to fitting the youth of the South for the duties of a lofty and broad-minded citizenship.

To the institution which Washington helped to found in such a spirit, Lee, in the same fine spirit, gave his services. He accepted the position of president at a salary of $1,500 a year, in order, as he stated, that he might do some good to the youth of the South. He applied himself to his new work with the same singleness of mind which he had shown in leading the Army of Northern Virginia. All the time by word and deed he was striving for the restoration of real peace, of real harmony, never uttering a word of bitterness nor allowing a word of bitterness uttered in his presence to go unchecked. From the close of the war to the time of his death all his great powers were devoted to two objects: to the reconciliation of all his countrymen with one another, and to fitting the youth of the South for the duties of a lofty and broad-minded citizenship.

Such is the career that you gather to honor; and I hope that you will take advantage of the one hundredth anniversary of General Lee’s birth by appealing to all our people, in every section of this country, to commemorate his life and deeds by the establishment, at some great representative educational institution of the South, of a permanent memorial, that will serve the youth of the coming years, as he, in the closing years of his life, served those who so sorely needed what he so freely gave.

Sincerely yours,