A classroom on a ferry in New York City, circa 1915. Credit…Bureau of Charities, via Library of Congress

In the early years of the 20th century, tuberculosis ravaged American cities, taking a particular and often fatal toll on the poor and the young. In 1907, two Rhode Island doctors, Mary Packard and Ellen Stone, had an idea for mitigating transmission among children. Following education trends in Germany, they proposed the creation of an open-air schoolroom. Within a matter of months, the floor of an empty brick building in Providence was converted into a space with ceiling-height windows on every side, kept open at nearly all times.

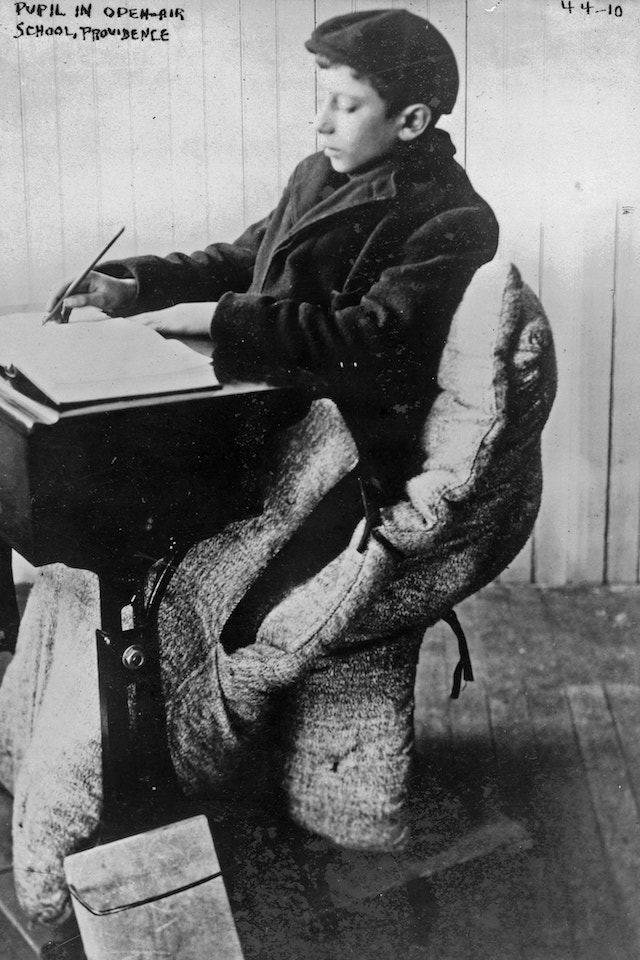

The subsequent New England winter was especially unforgiving, but children stayed warm in wearable blankets known as “Eskimo sitting bags” and with heated soapstones placed at their feet. The experiment was a success by nearly every measure — none of the children got sick. Within two years there were 65 open-air schools around the country either set up along the lines of the Providence model or simply held outside. In New York, the private school Horace Mann conducted classes on the roof; another school in the city took shape on an abandoned ferry.

Keeping warm in an open-air classroom, 1912. Credit…via Library of Congress

Distressingly, little of this sort of ingenuity has greeted the effort to reopen schools amid the current public-health crisis. The Trump administration has insisted that schools fully open this fall, with Education Secretary Betsy DeVos proposing no plan for how to do that safely.

In New York, the nation’s largest school system, students will attend live classes only a few days a week, a policy that has angered both exhausted parents, who feel that it is not nearly enough, and many teachers, who fear it as way too much.

At the same time, one of the few things we know about the coronavirus with any degree of certainty is that the risk of contracting it diminishes outside — a review of 7,000 cases in China recorded only one instance of fresh-air transmission. While this ought to have activated a war-room focus toward the goal of moving as much teaching as possible outdoors, nothing like that has happened.

“What I’m hearing instead is that people are looking at plastic shields going up around desks,’’ Sarah Milligan-Toffler, the executive director of an organization called the Children & Nature Network, told me. “That’s our creative solution?”

Public School 51 in Manhattan, 1911. Credit…via Library of Congress

Bureaucracy, it hardly needs to be said, is not inherently creative. And despite its self-image as an engine of innovation, the education-reform movement backed by Wall Street tends to recoil at anything that reeks of bohemianism. No hedge-funder, obsessed with metrics, achievement gaps and free Apple products has ever sat down and asked himself, “Hey, I wonder how they do it in Norway?”

Outdoor learning, though, is not a wood nymph fantasy; the body of evidence suggesting the ways it benefits students, younger ones in particular, is ever growing.

A 2018 study conducted over an academic year looked at the emotional, cognitive and behavioral challenges facing 161 fifth graders. It found that those participating in an outdoor science class showed increased attention over those in a control group who continued to learn conventionally. At John M. Patterson, an elementary school in Philadelphia, suspensions went from 50 a year to zero after a playground was built in which students maintain a rain-garden and take gym and some science classes, the principal, Kenneth Jessup, told me.

Recently, an examination of three groups of students in Bangladesh found that those who studied math and science in a transformed schoolyard did better academically than those who were contained inside. Beyond that, hundreds of studies over the years have demonstrated a positive correlation between engagement with nature and academics; some researchers have found that outdoor learning can improve both standardized test scores and graduation rates.

Art class on a New York City roof, 1912. Credit…Philipp Kester/ullstein bild via Getty Images

It is hard to imagine students similarly motivated by learning about the Civil Rights movement in an empty WeWork. While some have talked about using now vacant office or retail space for school, that would involve expensive leasing and little opportunity for fresh air.

So what could outdoor education look like in New York City? It would not mean sending the system’s 1.1 million children to Central Park every day (though Central Park, which accommodated hospital tents during the height of the pandemic, could easily hold some number of classroom tents with many other parks doing so too, as Adrian Benepe, the city’s former parks commissioner, recommended).

It is also possible that all kindergarten, first- and second-grade classes could be held outside, with the natural environment deployed as a resource for math and science education, as one public-school teacher proposed to me. Those grades account for nearly a quarter of all students in the system. Alternatively, schools could use as much accessible outdoor space as possible to reduce the number of students in a building at any given time, thus allowing for proper social distancing. Instead of rotating between live school and remote learning, children could rotate between indoor and outdoor work during the course of the day. As Ms. Milligan-Toffler, of the Children & Nature Network, has argued, reading, reflective writing and gym all lend themselves to being experienced outside.

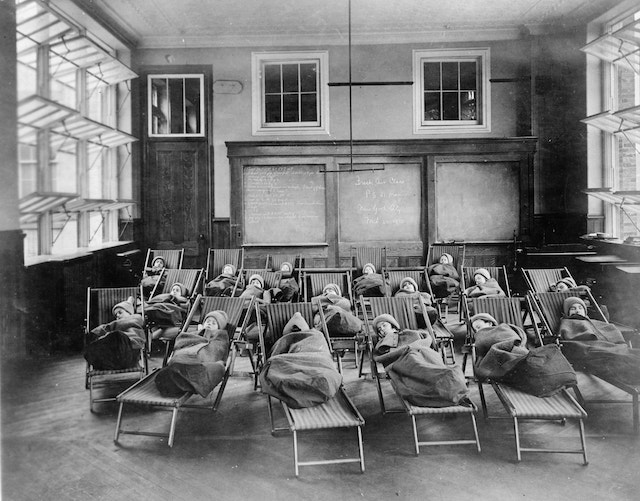

The earliest fresh air schools in New York were a success by nearly every measure. Within two years there were 65 open-air schools around the country.Credit…Bain News Service, via Library of Congress

While inequity has meant that schools in more affluent neighborhoods are situated closer to parks than those in poorer parts of the city, infrastructure for outdoor learning is already in place, even in many low-income neighborhoods. Between 2007 and 2013, in conjunction with the Trust for Public Land, the city converted more than 250 schoolyards to green space for student and community use. The New York City Housing Authority has 1,000 playgrounds that could be commandeered. And the Parks Department, as Mr. Benepe, who is now with the Trust, pointed out, has 35 recreation centers, already outfitted with gyms and bathrooms that could accommodate a few thousand children.

But as we head into late July, there is no indication that the de Blasio administration is pursuing any of this with a sense of urgency. In response to questions about plans for some movement outside, Jane Meyer, the mayor’s deputy press secretary, replied by email to say: “We are looking at all spaces possible, including outdoors, to see if learning can occur there.”

Wide-open windows keep the fresh air flowing in a cafeteria at Public School 51. Credit…via Library of Congress

Michael Mulgrew, the president of the local teachers’ union, who maintains there is still a good chance that school will not open in September, nonetheless seemed far more enthusiastic about that idea. When I caught up with him by phone he was reading air-exchange reports. Teacher safety is paramount to him, and he worried about windowless schools near heavily trafficked roads, which had been built to seal off pollution. “The best thing you can do is open a window,’’ he said. The idea of teaching in outdoor spaces with covering for protection from the rain is an extremely promising one in his mind.

Obviously, transitioning to this approach comes with challenges in terms of liability, curriculum flexibility and so on. But the reality of losing a generation of students to the deficiencies of Zoom seems much more troubling. On Thursday, Mr. de Blasio announced that the city was working on a plan to provide child care to 100,000 students in libraries, community centers and other locations on the days they are learning remotely, something that would seem less necessary if more attention were paid to learning outdoors.

Teachers, who are the ones in greatest jeopardy of getting sick when schools reopen, seem to be the most vocal proponents. “I do think it’s doable,’’ Liat Olenick, a schoolteacher in Brooklyn who has been advocating for outdoor learning during the pandemic, told me.

“Do I think it will be easy? No. But given that all our other choices are terrible it is worth considering.”

Written by inia Bellafante for The New York Times ~ July 17, 2020