Look back on our struggle for freedom,

Trace our present day’s strength to its source;

And you’ll find that our pathway to glory

Is strewn with the bones of a horse. ~ AUTHOR UNKNOWN

NOTE: THIS POST MAY BE DIFFICULT TO READ FOR SOME

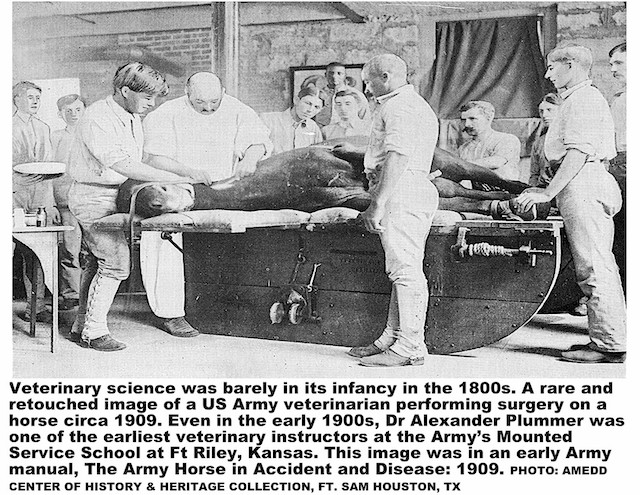

The Union Cavalry numbers during the first two years of the Civil War did not exceed 60,000 men. But yet 284,000 horses perished in the service of the Cavalry, few of them in battle. In the winter of 1863-1864 alone in the Union forces in Tennessee, 30,000 horses were lost. Why? Inadequate veterinary care. It wasn’t just “inadequate.” It was breathtakingly, completely absent.

The Union Cavalry numbers during the first two years of the Civil War did not exceed 60,000 men. But yet 284,000 horses perished in the service of the Cavalry, few of them in battle. In the winter of 1863-1864 alone in the Union forces in Tennessee, 30,000 horses were lost. Why? Inadequate veterinary care. It wasn’t just “inadequate.” It was breathtakingly, completely absent.

When the war started, there was not one single veterinarian in service anywhere in the Army. The quartermaster had the responsibilities of procurement, distribution, and supplying feed and care. And, each company usually had a farrier, but his responsibility ended after a horse was shod.

In fact, it was the humanity of President Abraham Lincoln, who was horrified by the appalling mistreatment of horses and mules that instigated the first official order to hire veterinarians for cavalry regiments. When he was asked to sign an authorization for a Sixth Cavalry Regiment in May 1861, Lincoln agreed under one condition: he added a presidential paragraph requiring that each of the six regiments would have a staff veterinary sergeant that would be paid the princely sum of $17 per month!

In 1863, in answer to the need for veterinarians for the war effort, the American Veterinary Medical Association was formed. And a second major Presidential order was signed that year: every cavalry regiment would have a veterinarian surgeon with the rank of sergeant-major and the pay of a first lieutenant of $75 a month.

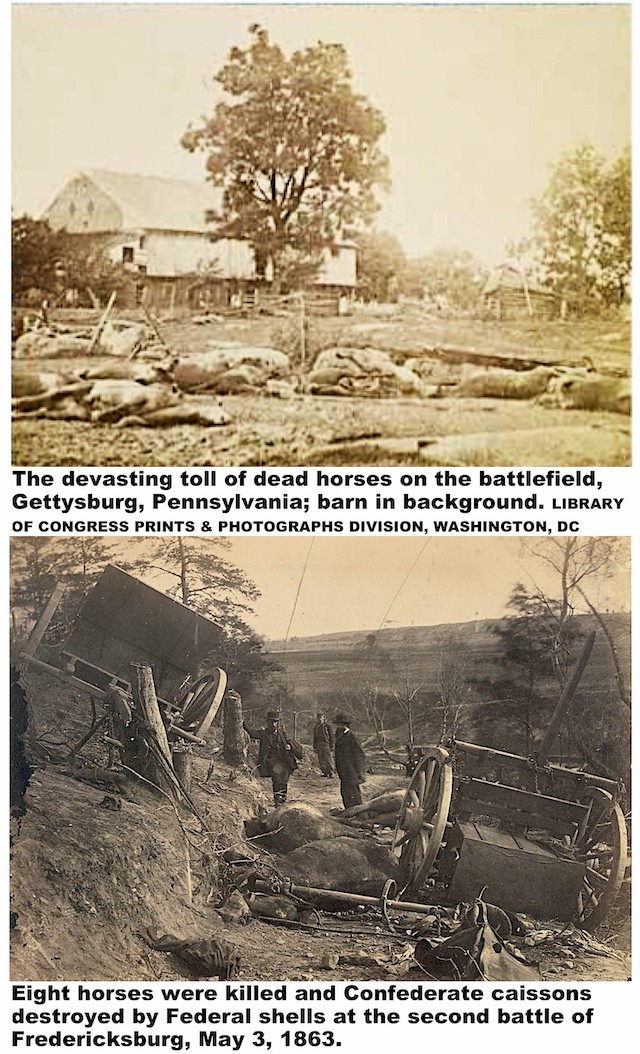

But Abraham Lincoln and the Army veterinarians could not protect Civil War mounts from the many perils that faced them that included not only warfare, but disease, overwork, abuse, and neglect. By some estimates, 1.2-1.5 million horses died during the Civil War. Like their human counterparts in war, many more died from disease, neglect and poor care than from battle wounds, although battle was extremely dangerous for horses and mules. They were larger and much easier targets and opposing forces often shot a horse out from under a rider first before taking aim at human targets.

The process of procuring horses and mules was one huge problem for both Armies, for large numbers of purchased animals were housed in crowded corrals, hock-deep in mud and excrement, inadequately fed and watered in common troughs that spread disease. The dreaded equine disease, glanders was a lung disease that spread into the bloodstream and killed many horses, was also communicable to humans and reached epidemic stages in man and horse during the war.

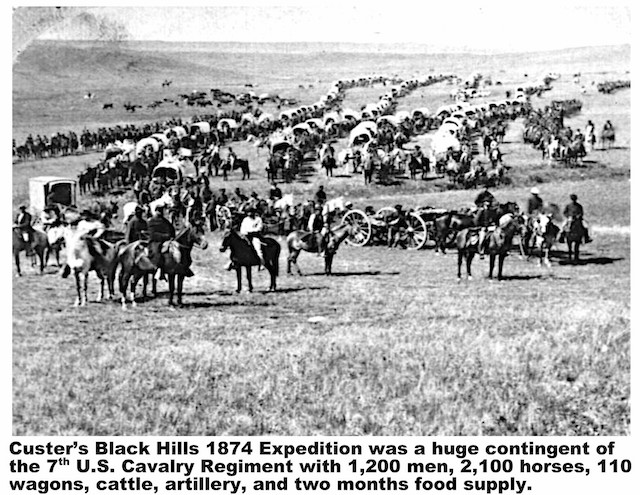

When the war was over, General George A. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry was the first of four new postwar regiments to be activated before the end of 1866. The regiment immediately saw hard service in the West, from the Platte to the Washita. On July 2, 1874, Custer was given the charge of setting out from Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory to investigate the uncharted Black Hills and to confirm if rumors of gold in the area were true. His 7th Cavalry had with it an immense contingent of about 1,200 men, 2,100 horses and mules, 110 wagons, and a two-month supply of food and forage for the horses.

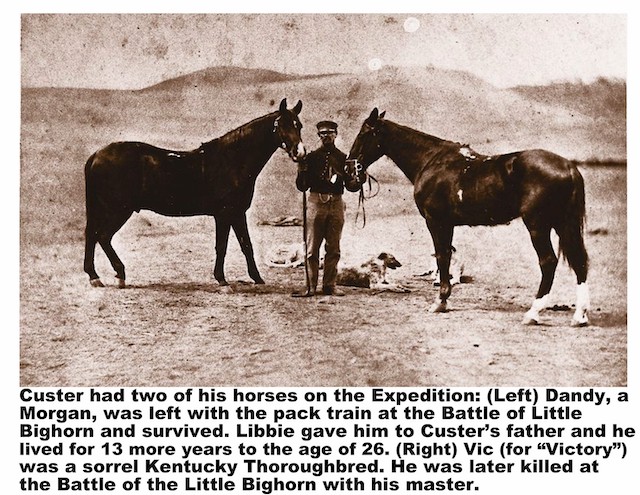

Custer was infamously hard on his own personal horses. (He had reputedly had 11 horses shot out from under him during the Civil War.) He also required often grueling forced marches of his men and their horses. Custer brought his two favorite horses with him, a bay Morgan named Dandy, and a sorrel Kentucky Thoroughbred named Vic, short for “Victory.”

The dashingly-mustachioed general thoroughly enjoyed exploring and when his expedition came upon Mount Harney, a mountain named after a white man but never scaled by one, Custer resolved to do so. He and his principal officers rode up the grueling 7,500-foot mountainside but, for the last several hundred feet, all but Custer tethered their horses and climbed on foot, so rocky was the terrain. But Custer forced his sorrel Thoroughbred to the very top and then down again, Vic’s legs bloodied and cut and his ribs heaving with such extreme exertion.

Later, during the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Dandy had luckily been left behind with the pack train and lived for another 13 years after his master was killed. Libbie Custer gave him to Custer’s father, where the horse lived to the ripe old age of 29. Vic was not so lucky and was killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Some historians believe Vic was shot by Custer when he ordered his men to shoot their horses to create a bulwark for cover against their assailants.

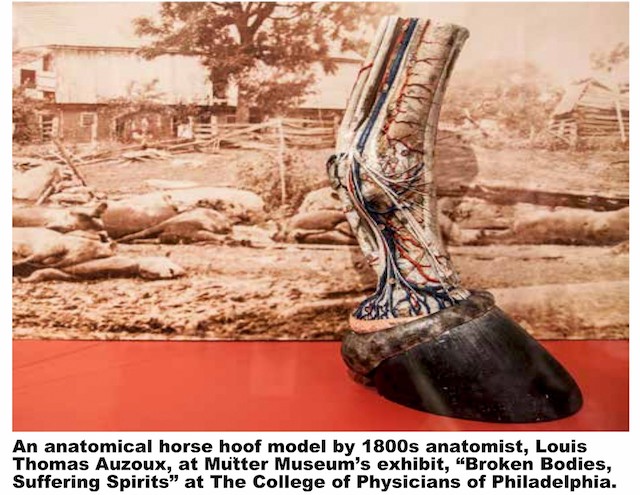

The two greatest perils for cavalry horses, besides being wounded by bullets or arrows, was exhaustion and lameness. Forced marches over very rough terrain were grueling and long marches did not allow for recuperation time.

Another problem was over-exertion and underfeeding of mounts. Average daily forage for one horse is about 14 pounds of hay or 12 pounds of grain per day, more if the mount is ridden strenuously. Providing adequate forage for moving columns presented towering challenges. Local contractors could sometimes be hired, but more often rations had to be carried on pack animals. It was not until after the Civil War that General George Crook perfected the military pack train to carry forage and other supplies. Because mules are legendary for being able to survive on far less and far poorer forage than horses, they can often outmarch a cavalry. But many officers failed to adopt Crook’s system and subsequently failed to keep their cavalry horses fed adequately. Shortchanging a horse of its feed limits mobility and speed of a cavalry and also renders horses more prone to exhaustion and disease.

On the misty morning of May 17, 1876, the Dakota column paraded out of Fort Abraham Lincoln to launch a summer campaign against the Sioux. Dr. Charles Stein, a German immigrant with a large family in New Orleans, had accepted his fateful appointment as veterinarian for Custer’s Sioux campaign. His first duty was to inspect the cavalry horses for preparation of the campaign. At the beginning of April, he reported that, of 722 cavalry horses, 39 were unserviceable. By the end of that month, however, he had reduced the number of serviceable saddle horses to 644. That was a problem since there were 718 enlisted troops that required mounts.

So, when the column marched out from the fort that morning, prophetically, 64 disgruntled recruits scuffled on foot at the rear, without horses. One of them, Pvt. Jacob Horner, wrote an account of the hardship of tramping 318 miles to the mouth of the Powder River in new boots that gave him blisters, eating the dust of his more privileged comrades. But, in the end, not having a horse saved his life, for he wasn’t able to ride into battle at the Little Bighorn.

At the Powder River, about 150 more men were detached due to a growing shortage of horses. On June 10, Captain Reno took a wing of the Seventh with a pack train of full rations for his troops but only two pounds (one-sixth of a full ration) of grain daily for his horses. He followed the trail of “the hostiles” for 240 miles in 10 days and returned with many lame, emaciated mounts.

On June 22, Custer led his reunited regiment down the valley of the Rosebud, averaging about 26 miles a day for three days. Then they began a grueling eight-mile ascent up the Divide. By then, the Seventh Cavalry mounts must have been exhausted. But the worst was yet to come.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25 took a terrible toll of men but even an even greater toll of horses: 268 men of the Seventh rode to their death, but 334 horses perished. In the aftermath, veterinarian Dr. Elwood Nye wrote that Custer had driven the Cavalry horses so hard that their failing condition contributed significantly to the disaster, not only in impairing their performance, but in limiting quite severely the number of mounted soldiers available for the conflict. His conclusion, in a nutshell: “For want of a horse, the battle was lost….” Although many other experts rejected that conclusion, it sparked closer examination of how inadequate horse care impacted the effectiveness of a fighting force.

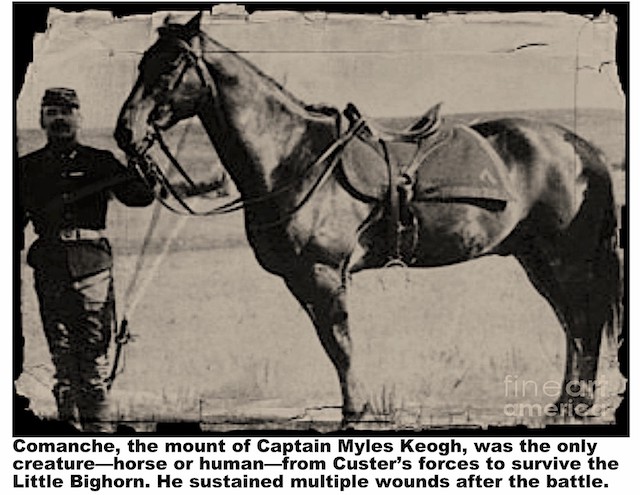

Of course, there was reputedly one survivor of the Little Bighorn Battle, the famous Comanche. Evan S. Connell, in his seminal work, Son of the Morning Star, wrote of how Comanche was found after the battle:

Cpl. Henry Brinker saw Comanche in a club of trees and was ordered to shoot him but had not the heart to carry out this order when the horse whinnied to him. Capt. McDougall found him “sitting on his haunches, braced back on his forefeet,” pocked with arrows and bullets, in very poor shape…. Seven grievous wounds he suffered “each of which would have killed an ordinary horse,” according to one newspaper tribute.

The St. Paul’s Pioneer Press reported that “Captain Keogh’s horse was alive, notwithstanding he had twenty bullets in him. Dr. Stein [the regimental veterinary surgeon] immediately went to work to extract the bullets and succeeded in cutting out thirteen of them.”

A reporter for the Bismarck Tribune went to Fort Abraham Lincoln to interview Comanche. He “asked the usual questions which his subject acknowledged with a toss of his head, a stamp of his foot and a flourish of his beautiful tail.” Comanche’s official keeper, Army farrier John Rivers of Company I, Keogh’s old troop, assisted Comanche in answering the reporter’s questions more fully. The article stated:

Comanche was a veteran, 21 years old, and had been with the 7th Cavalry since its Organization in ’66…He was found by Sergeant [Milton J.] DeLacey [Co. I] in a ravine where he had crawled there to die and feed the Crows. He was raised up and tenderly cared for. His wounds were serious, but not necessarily fatal if properly looked after ….He carries seven scars from as many bullet wounds. There are four back of the fore shoulder, one through a hoof, and one on either hind leg. At Fort A. Lincoln, three of the balls were extracted from his body and the last one was not taken out until April ’77…Comanche was given his name by his owner after he was hit in the hindquarters with a Comanche arrow in 1868 in Kansas but continued to carry his rider to safety.

The surviving horse that had sustained so many wounds was finally retired. As an honor, Comanche was made “Second Commanding Officer” at Fort Riley, Kansas, and spent much of his time being fawned over by loving cavalry members and being fed mugs of beer, which he had taken a liking to. He died at age 29 and was one of only three horses in U.S. history to be given a military funeral. When he died, he was stuffed and stands at eternal attention behind glass at the University of Kansas. His hide bears numerous scars from bullets and arrows suffered while in service with the Seventh Cavalry. The many healed scars are a testament to Army veterinarians and their crude fledgling science, as well as Comanche’s own legendary toughness.

Written by Deborah Hufford for Notes From the Frontier