This famous depiction of the Boston Massacre was engraved by Paul Revere (copied from an engraving by Henry Pelham), colored by Christian Remick, and printed by Benjamin Edes. The Old State House is depicted in the background. / Library of Congress

Different Conceptions of Colonists’ Relationship to Britain

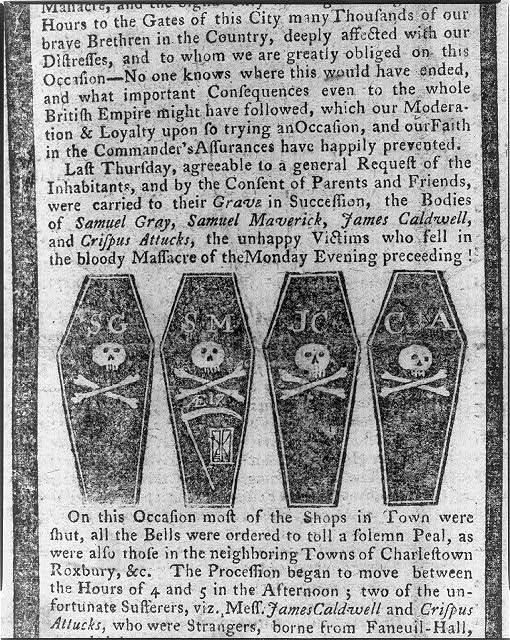

Article by Samuel Adams in the Boston Gazette about the Boston Massacre

Following the the Boston Massacre in 1770, there were different ways in which both onlookers in the British government and the colonists ended up wondering, each one, if the other one was somehow engaged in a plot. Right? And I mentioned that the British were perhaps wondering if this had all been a plot to rob the customs house; the colonists were wondering about the possibility of this being some kind of ongoing plot to subdue and repress the American colonists. So clearly at the end of the lecture from last week you can really begin to sense a growing sense of mounting hostility, even among some people a sense of growing alienation.

And you can hear this on both sides coming from the accounts of the Boston Massacre by both Gage and Adams. And I did mention in class when I read from them that they were of course writing with a purpose in mind so they were interested in being particularly bold and dramatic in what they were saying. Gage really had to excuse what happened and Adams was trying to promote people to get upset about what had happened, but even so you can hear even just in the way that they framed their accounts some of what I’m talking about here with growing hostility, growing alienation.

Report from General Thomas Gage to Thomas Hutchinson about the Boston Massacre

So for example, Gage at the very start of the letter that I read from in the last lecture tells the person he’s writing to that he’s writing this letter to inform the King’s ministry, quote, “of the critical situation of the troops and the hatred of the people towards them.” That’s how he starts his letter, which is really interesting. So to Gage, clearly, what he’s stating in this letter to his people back home within the King’s Ministry is that it doesn’t really even feel safe for British soldiers on the streets of Boston; the people here hate us.

And Adams also emphasizes this kind of growing alienation and animosity, and in his case he does it in a particularly strong way in a series of newspaper articles for the Boston Gazette that he wrote a few months after the massacre. So Adams writes: “I appeal to the common sense of mankind. To what a state of misery and infamy must a people be reduced! To have a governor by the sole appointment of the crown; under the absolute control of a weak and arbitrary minister, to whose dictates he is to yield an unlimited obedience, or forfeit his political career [correction: existence]: while he is to be supported at the expense of the people, by virtue of an authority claimed by strangers.” And that’s really an interesting statement. Strangers — He’s referring to Parliament. Right? It’s these strangers who are telling these officials what to do. That’s again a striking word and a striking statement.

Now of course, here Adams says that really striking thing — and then he’s careful to add right after it that [correction: in another article shortly thereafter], quote, “For opposing a threatened tyranny we have been not only called, but in effect adjudged rebels and traitors to the best of kings.” OK — He’s making a really important distinction there. He’s saying, ‘Yes, maybe we’re upset at what Parliament is doing, maybe Parliament is behaving like a group of strangers, but we are still good British subjects and we are loyal to our King, to the best of kings.’ And it’s an important point, that even in the midst of all of this animosity and all of these misunderstandings, troops are in Boston streets and the colonists obviously still feel like British subjects who are loyal to their King and who are objecting because their rights as British subjects are being violated. That’s the logic that we’re working on here.

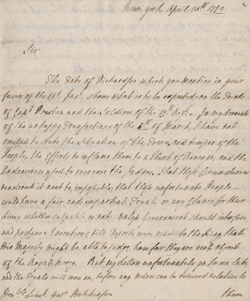

In this c. 1772 portrait of Samuel Adams by John Singleton Copley, Adams points at the Massachusetts Charter, which he viewed as a constitution that protected the peoples’ rights. / Library of Congress

And you can see this in Samuel Adams’ actions. At the same time that he’s writing all these sort of propaganda newspaper accounts and trying to stir up animosity, he also was writing letters to people in England trying to persuade them and hopefully inspire them to persuade others that the people of Boston were rightfully defending their liberties and deserved to be defended by people in Parliament, not condemned and punished. Equally important, the colonists were not saying that they wanted nothing to do with Parliament, or even that Parliament had no authority over the colonies — even though the occasional bold statement sort of runs out on an edge and says ‘we hate Parliament.’

Most colonists thought that the colonists — the colonies were subordinate to Parliament in some way. The problem, Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson later remarked, is that subordination, quote, “was a word without any precise meaning to it.” Okay? That’s a really insightful comment. Yeah, okay, colonies are subordinate but what does that mean? And obviously what we’re looking at now is a sort of non-debate debate in which it’s clear people have different understandings of exactly what the imperial system is supposed to look like and how it functions.

So all in all it’s important to remember here that even with all of this friction that we’re seeing between colonists and the British, the colonists are still loyal British subjects who want the imperial system to function happily again. And this is a really great example of why it’s always important — and I think it’s particularly important when studying anything in the founding era, but I think history generally — but when studying the Revolution or the founding era — but when studying the Revolution, it’s important not to jump on to the independence bandwagon too quickly and assume that a separation is inevitable, because the people that we’re studying did not assume that. It’s so easy for us to assume that, right? Because we know it’s coming — but remember Freeman’s Top Tips for Studying the Revolution, right? Contingency.

Our historical subjects didn’t know what was going to happen — and anything could have happened. So from our perspective, we’re looking at the events here — we almost can’t help it, I think on all of our parts, even on my part. It all looks like a ticking clock, like there’s an inevitable pulling away from the British, and everything I talk about here represents one step closer to independence, another step closer to independence. And part of what I’m trying to say here is: clearly that’s not how the colonists or the British at this point are thinking. That’s not how they understand their actions. That’s not how they understand what’s happening. The colonists at this point are not trying to rebel and they’re not trying to retreat away from the British empire. They’re trying to fix things. They’re trying to figure out how to fix things.

So in a sense, the best way to understand the events of the first half of the 1770s is to look at the whole revolutionary era without thinking about the Revolution, and by that I mean the war. Just forget that there’s going to be a war. The war doesn’t exist. I — Always as a historian I do this to myself when I’m sitting down to write something, like if I’m writing a project — as I’m working on a book now that takes me up to the Civil War, so I have to constantly say, ‘Civil War? I don’t know if they had a Civil War. What Civil War?’ Because my subjects aren’t assuming until a very late point that there might be one. And I’m sort of saying the same thing here, that it’s useful to just sort of put the assumption that there’s going to be a war over here and watch the logic of events as they unfold. It’s a good reminder I think for the study of history generally, because part of what you’re trying to do as historians is understand what your historical subjects are thinking and why they’re thinking that way, and you make that much harder when you stick the outcome right in front of them and compare what they’re doing with what you assume to be an inevitable outcome. Okay.

The Growth of Non-importation Associations in the Colonies

Now, I mentioned last time that one way in which the colonists responded to the Townshend Acts was to propose boycotting British goods again, as they had before — in their minds successfully — with the Stamp Act. So now, feeling even more threatened, the colonists didn’t simply urge a boycott in an informal way. Now they actually organize. So remember there’s a pattern I pointed out in an earlier lecture when I was talking about previous attempts at colonial union, and I mentioned in that lecture that one of the main things that really drives the colonies to join together in an effort is some kind of a threat — so basically self-defense is a really good motivator.

A non-importation agreement responding to Townsend Acts, October 28, 1767. Signed by 650 Bostonian colonists, including Paul Revere. This is the first of several pages. / Houghton Library at Harvard University

And so typically in the past something would threaten the colonies, inter-colonial unity suddenly seemed important, there’d be some kind of a movement to do something together for the moment, and then when the crisis passed the unity passed as well. So we’re sort of seeing some of that go into operation here. Way down the road for Americans, one of the big lessons of the Revolution would ultimately be how powerful it is when you combine and organize and associate — when you form associations or organizations — and as we’ll begin to see soon, when people organize into small coordinated groups, they can have an enormous impact — and that’s essentially what happens here in the course of the American Revolution.

So between 1768 and 1770, as they begin to contemplate boycotting British goods yet again, people begin to form non-importation associations, okay? Non-importation associations. Now these associations — these organizations in a sense — were extra-constitutional, so they’re springing up from outside of the formal political system, but in a variety of different ways they actually had some real power. In the North, merchants were at the core of this movement, this non-importation association movement, although it was grounded on popular support, but merchants were really at the center of it because one key to the success of this whole endeavor was for merchants to join together in promising not to import British goods. And sometimes merchants actually signed written agreements that they would not import British goods, so unity among the merchants could be a powerful thing and in the North that operated pretty effectively.

So for example, when — And I swear I’m really not inserting Rhode Island into every moment in which a random bad thing happens. Today we have two — at least two — several Rhode Island moments, and every time I come across one I think, is it just because I’m aware of Rhode Island? Is it because I’m thinking about Rhode Island that Rhode Island appears to be there so much? But it makes me think of — I got my undergraduate degree at Pomona College in California, and Pomona has a thing about the number forty-seven, which they think appears everywhere, right? Everything is forty-seven, so when you go to Pomona, it’s like the magic of forty-seven constantly being talked about. You add letters up to various things, and it always equals — ooh! — forty-seven, and then people graduate from Pomona and go on to become film writers and then you’ll see all these forty-sevens. Everyone’s like: there’s another one in Star Wars; it’s a forty-seven! So forty-seven was the Pomona thing and after a while you begin to think well, if I’m looking for forty-sevens I’m always going to find forty-sevens. So today I actually — when I was writing this, I thought, maybe I’m doing that to Rhode Island. I hope not, but here is a Rhode Island moment, okay? And it’s an actual Rhode Island moment.

White Horse Tavern in Rhode Island, built 1652 / Wikimedia Commons

Some Rhode Island merchants threatened to pull out of the non-importation agreement because it’s proving to be troublesome in a variety of ways, so when these Rhode Island merchants threatened this, merchants in Boston and New York and Philadelphia actually imposed a boycott on Newport and Providence, Rhode Island. Right? Okay. There’s the power of association. ‘Oh, you’re going to — think you’re going to import British goods? Okay. We boycott you, Rhode Island.’ [laughs] ‘You’re now going to be boycotted.’ That’s pretty powerful. So merchants were key here, as was the public.

So for example, in various places in the North, colonial legislatures sometimes passed resolutions commending these non-importation associations to the people. Right? The people are vital too. So you have colonial legislatures passing resolutions to the public saying, this whole association effort here is good and you should really listen to it, basically lending legitimacy to what were essentially really ad hoc organizations, ad hoc committees.

Now in the South, the non-importation associations were more centered on the populace, not quite as centered on merchants, so southern non-importation associations were often very careful to have members sign on from throughout the community, so not just merchants but artisans and planters. And because in the South they were more popularly based, they were more centered on non-consumption than on non-importation — but of course if you’re looking at the North, it’s all about seaports and importing goods. It makes sense that in the South, maybe there’d be more of a focus on not consuming imported British goods, as opposed to not importing British goods.

Now as suggested in the comments that I just made about northern legislatures supporting northern non-importation associations, it’s important to note that these are not rebellious groups acting against the structure of colonial government. They’re not competing with colonial assemblies. They’re actually in some ways acting in harmony with them, and as a matter of fact some people who were in these non-importation associations probably were in the colonial legislatures too. So we’re not talking about opposing efforts. We’re talking about sort of parallel efforts that sometimes intersect.

Okay. So as organizations linking the will of the people with politicized action, these associations are pretty significant because — I’m sure you can see now just based on my description of them — they’re really promoting broad, popular, organized, coordinated politicized action. And this model is going to become more and more significant as the Revolution continues on. And broadly based as they were, these associations really did help to spread a sense of popular involvement in resistance to British policy.

Boycotting British goods was a political act and everyone from all levels of society including women could be involved in this in some way, spreading a real sense of popular involvement in acts of resistance to these seemingly unfair acts of Parliament. So average people — we’re not just talking legislators and political radicals like Samuel Adams — but average people had a sense of involvement in a larger cause. And newspaper articles and broadsides helped spread this sense of involvement, urging the colonists to avoid luxuries like imported silks or English rum, and instead people should be virtuous and they should wear homespun clothing made of cloth that could be made in the colonies, and they should drink whiskey and beer and cider that could be made in the colonies.

Whiskey bottles from 1770 / The Chipstone Foundation

Now you’ll notice things to drink include whiskey, beer and cider, but you’ll notice water isn’t included in that list — and actually it wasn’t considered a normal beverage at this point in time, which I always thought was an interesting fact. And when I was in grad school I read this really interesting British novel written in 1796. It has a very strange title. The title is Hermsprong; Or Man As He is Not. There were a lot of novels at the time called Man as He is, Man as He is Not — but what Hermsprong is about, among other things, is: the central character is this American in England, and he’s this sort of exotic, strange, independent-minded creature. And two things that he does that are sort of shockingly bizarre to all of the British onlookers in this novel is: he walks places instead of riding in a carriage. ‘Oh, my gosh. He got up this morning from the tavern and went walking.’ And then the second even more horrifying thing is: he drinks water. [laughter] He drank water. He had a normal dinner. He drank water. And there’s a weird scene in it in which someone says, ‘I can’t even describe to you what water tastes like. Why do you drink it? Water has no taste.’ ‘Water tastes like,’ Hermsprong says, ‘water.’ [laughs] Water tastes like water. That was kind of radical. So, being very patriotic here, drink whiskey, beer and cider, period. [laughs] Don’t worry about that boring water stuff. It’s fascinating that that’s considered a weird thing at that time.

Okay. So people are encouraged to drink and wear only colonial-made goods, and this was true all over the place. So as a symbolic gesture, Harvard students gave up drinking tea. Students at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton, wore homespun clothing. And students at Yale [laughs] — I wonder what this says about Yale — renounced imported wines. [laughter] Huh? [laughs] I actually went and double-checked that. I was like: really? [laughter] Yeah, really. [laughs] Yale. Okay. South Carolina assemblymen renounced the wearing of wigs and stockings — which must have looked very odd — with the result one observer noted, that a foreign visitor arriving in Charleston, quote, “would probably from their dress take them for so many unhappy persons ready for execution who had come to petition for a pardon.” [laughter] Some of these people with no wigs and no — kind of dressed really badly and hanging out in the legislature. Okay.

So clearly, based on those examples, even Yale students, non-import — although maybe I don’t know about the — [laughs] not having imported wine. Non-importation does represent one way in which many people, and as I said before including women, became directly involved in colonial protest efforts. But women were often the primary purchasers of goods, so their actions were central on this front. They had to be appealed to, they had to be included, so non-importation politicized the daily activities of women as well as men, spreading feelings of community-level patriotism with people joined in a joint political effort to defend their rights. So you have people who are sort of joined in this effort of patriotic austerity; they’re all sort of joining in a willingness to sacrifice luxuries for a worthy cause. Now of course not every American and not every colonist is doing this, so when I say “joined, everyone’s joined,” maybe not everyone, but there were a lot of people who were paying attention to this idea of non-importation.

Taxing as Display of British Supremacy: Parliament’s Reactions

Portrait of Frederick North by Nathaniel Dance-Holland / National Portrait Gallery, London

But of course, now that I’ve made non-importation sound so impressive, I will add that it ultimately was not a roaring success because, as I just hinted a minute ago, not everyone really found it very easy to surrender English luxuries, and as always there was a lot of smuggling. So it wasn’t an amazing roaring success but that said, there was some impact on British manufacturers and there was some recognition that considering the relatively small amount of revenue being raised by the Townshend Acts, maybe the effort wasn’t worth all of the trouble.

So some onlookers in Britain began to regret the Townshend Acts. And it’s important to note even Members of Parliament who were sympathetic to the colonies and who wanted the Townshend Acts repealed — even these sympathetic Members didn’t question the right of Parliament to tax the colonies. They may have felt that Parliament was behaving too aggressively or unwisely, maybe it’s an unwise policy, but even people who were — considered themselves sort of supporters, real dire supporters of the American colonists, even they were not questioning the constitutional supremacy of Parliament to tax the British colonies. That’s almost like a line in the sand.

So along these lines, despite the fact that you have some people in Parliament who are sympathetic towards the colonies, Parliament could not just back down and take all of the Townshend Acts back, and there are two main reasons for that. There’s such power when you say that: ‘there are two reasons’ — and a hundred people go “gonk.” Satisfaction. Note-taking. But there are two main reasons. First and most obvious, Parliament just didn’t want to lose face. Right? They felt that they truly were upholding the supremacy and sovereignty of the British Parliament. Second, related to that and perhaps more important as far as our understanding of different — two evolving mindsets is concerned, the sovereignty of Parliament over the colonies by this point had become inextricably bound up with the right of taxing Americans. And I’ll repeat that again. By this point, the sovereignty of Parliament over the colonies had become inextricably bound up with the right of taxing American colonists.

So at this point, Parliament couldn’t back down on a tax without seeming to give up their sovereignty over the colonies. By 1770, the right of taxation was not just a means of producing revenue for the British, but it actually had become an assertion of British sovereignty over its own colonies.

Okay. So now we’re in 1770 and surprise, surprise, by this time we have a new Prime Minister. Lord North is now Prime Minister. Townshend is gone, although we’re sort of in a period of revolving doors of Prime Ministers, but in this case Townshend died. Townshend actually died back in 1767 and so Lord North is the next person who comes along. Townshend’s Acts live on without him for a little while, but now Lord North is the Prime Minister so he assumes this position and with familiar logic he decides that the only way to withdraw the Townshend Acts is going to be to leave behind a token tax in the colonies to prove that England reigned supreme over its colonial properties. As Lord North himself put it,

“If I thought I could appease that factious and disobedient temper which prevails [in the colonies], I should be glad to do it. And yet, to these people, who ought to be our subjects, we are to make concessions, because they have the hardihood to set us at defiance! . . . Upon my word, if we are to run after America in search of reconciliation, in this way, I do not know a single act of Parliament that will remain.”

But despite having said all that, North concluded this speech by saying he wanted to be, quote, “thought, what I really am, to the best of my conviction — a friend to trade, a friend to America.” Okay. There’s a lot of stuff bound up in that statement — but you can really see him processing through what’s happening versus what he assumes about the workings of the imperial system. It’s a complicated situation to North and the British as well as to the colonies.

Tea Tax illustration in the Boston Gazette / Wikimedia Commons

So in the end, thinking about all of this and thinking well, I need to leave some kind of tax in place to prove Parliamentary supremacy, he decides to leave the tea tax in effect, and the logic behind that is, of all the taxed items this was the most profitable to England, and it couldn’t be manufactured in the colonies, so it would have to be imported — plus it was kind of central to socializing. Everybody drank tea. That was the thing to do — was to drink tea with great ceremony — among some people to have tea cups and tea spoons — so North just assumed on a whole bunch of levels: can’t be easily boycotted; they really like tea in those colonies, just like us here; makes us a reasonable amount of money; that’s the thing that’ll stay.

Now when I was writing this lecture, I was thinking about that. I was thinking about tea and tea ceremonies and the drinking of tea, and I suppose we all have in our mind a sense of that being the case in England, but it was no less the case in the colonies. And when I was — I guess when I was researching my first book I came across a story. I’m going to mention it now only because it relates to the tea ceremony and this is my opportunity to tell this story. There will be random moments when I just have to tell a story ’cause you guys are like hostages. [laughter] It means I get to say whatever I want and I get to tell random stories — but this actually does demonstrate the sort of ritual of tea drinking everywhere.

So the whole tea ceremony was important in the colonies. I came across this account from a foreign observer, actually from France. And he shows up in the colonies, and he says in a letter to a friend that he’d never quite seen anything like the colonial obsession with serving tea. And he describes this visit that he paid to a woman, and he said that he would take a sip and then she would immediately refill the cup, so he couldn’t figure out how to empty the cup. Basically, he doesn’t want any more tea [laughs] and he can’t figure out how to make it stop coming. ‘I’ll drink a little more fast. Maybe she’ll’ — And he kept basically trying out one thing after another and she kept refilling the cup — and then he felt compelled to drink, because it was the proper thing to do — was to eat or drink what he was served. He didn’t know that the code in the tea ceremony to stop tea from being poured was to place your tea spoon across the top of your cup. Right? He didn’t think about that, so at one point he’s desperate, because he just can’t deal with any more tea. So she pours more tea in his cup and when she turned away he actually swallowed everything in the cup in a gulp and then put the cup in his pocket. [laughter] Like she’s not going to notice. [laughs] Right? Oh, you ate the cup. [laughter] And he doesn’t say what happened. He just describes putting it in his pocket like: There. Now I’ve settled that. Great thinking. [laughter] They were serious about tea ceremonies. Okay.

The Impact of the Tea Tax and the Development of Committees of Correspondence

1777 map of Boston by Thomas Hyde Page / Library of Congress

So with full knowledge of the cultural importance of tea in the colonies, North left the tea tax in effect, hoping that a slight concession on the part of England maybe would chip away at colonial unity. Right? Maybe some colonists would be convinced to stop resisting, maybe non-importation would thus collapse — and eventually non-importation does collapse. It kind of dribbles to a close — 1770, 1771. And as with the Stamp Act, both the colonies and the British administration assumed that they had emerged from this victorious. Right? The colonies think ha, we got most of those offensive acts repealed. Parliament thinks well, we are still maintaining our sovereignty so our point stands firm. And of course this did nothing to resolve the conflict about the precise nature of sovereignty, the precise nature of the imperial system, and the precise power of Parliament over the colonies.

At about this time, however, Lord North once again, thinking about the colonies, attempting reform, he’s struggling clearly. I just feel bad for a Prime Minister at this moment of massive confusion in the colonies. He’s trying to figure out some way to get colonial affairs in control, so at this point he figures maybe one way to sort of calm things down is to focus on Massachusetts. Right? Massachusetts is the pesky colony, bad things happen in Massachusetts, so he says maybe one way to resolve things is to make a few little tweaks in their political system. So he decides that henceforth Superior Court judges will be paid by tax revenue collected by the Crown from the colonies, which means in effect Superior Court judges are not going to be paid by colonial legislatures; they’re going to be paid by the Crown. Okay.

So certainly to some people in Massachusetts this seemed like it’s a way to make judges accountable to British authorities and not to colonists, and in a sense that was part of what North was trying to do here. But unfortunately about the same time, in June of 1772, there was a crisis in Rhode Island. [laughter] A British ship, the Gaspee, which was used in Rhode Island to prevent smuggling, ran aground in Rhode Island and that night colonists swarmed aboard it, forced the crew off and burned it to the ground. That’s kind of a strong anti-British “we hate that you’re stopping smuggling” act. So the Crown responded by creating a commission of inquiry to investigate the matter, and ultimately this committee decides it’s going to let this slide, which is a major concession because [laughs] burning one of His Majesty’s ships is a serious matter. Right? It’s not a minor crime.

Even so, colonists just took offense at the existence of the commission which seemed to interfere with the internal affairs of a colony, and even worse — this gets back to something that people have been upset about in the colonies before — the commission would have sent the people who were going to be tried to England for their trials, right? So — and this also feels like a threat to self-rule. So you have these sorts of things going on. They’re individual acts. They’re not connected, but they’re — in the eyes of many colonists not good things.

Statue of Samuel Adams in front of Faneuil Hall, which was the home of the Boston Town Meeting / Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Adams, brilliant propagandist that he is, decides there has to be an immediate response to these new encroachments on colonial rights and it needs to not just be in Boston. There needs to be a widespread inter-state protest to what’s happening and to the implications of what’s happening. So in November of 1772, building on the whole model of the non-importation associations, he suggests in the Boston town meeting that a committee of correspondence be formed in Boston to communicate the current state of affairs in Boston to the rest of the colony and, quote, “to the world” — right? He’s ambitious, Samuel Adams — and to solicit responses. So a committee of correspondence of roughly twenty-one men is created with the purpose — as stated in the Boston town meeting — of stating, quote, “the rights of the Colonists and of this Province in particular, as men and Christians, and as subjects” — which is an interesting trio — as men, as Christians and as subjects, and “to communicate and publish the same to the several towns and to the world as the sense of this town, with the infringements and violations thereof that have been, or from time to time may be, made.” Right? Infringements that have been made or may be made, right? So he’s even — Something else is going to happen, and if it is, we’ve got a committee of correspondence in place.

So by the end of November of 1772, the committee had produced an open letter to all of the towns in Massachusetts urging them, quote, not “to doze or sit supinely indifferent on the brink of destruction” — that Samuel Adams; he’s really a master at the strong words — and to create their own committees of correspondence. And more than half of the towns in Massachusetts responded, encouraging more widespread participation in the controversy than before, more widespread willingness to act alongside the normal political system to protest what people saw as an unconstitutional act — and there were more than eighty of these local committees of correspondence created within just a few months.

One observer called these committees, quote, “the foulest, subtlest and most venomous serpent ever issued from the egg of sedition.” And you can kind of see this person’s fears. Right? This is a person who sees what he perceives to be as organized resistance to the British government sort of bubbling up in Massachusetts. And this sort of bubbling committees, these committees of correspondence are going to be spreading sedition, according to this person, throughout the colonies and possibly to the world. And this person had a right to be suspicious, because organized resistance is partly what these committees are all about.

So this unfolding of events in Massachusetts led radicals elsewhere to do what Massachusetts had done, and create their own committees of correspondence for communication within colonies and between the colonies. So within roughly a year, by very, very early in 1774, there were committees of correspondence in almost every colony. And these committees did a number of things. They strengthened ties between radical colonies like Massachusetts and less active or less-radical colonies, and they created a way for radical-minded people in different colonies to interact with each other. So clearly these committees of correspondence — just like the non-importation associations — are an important stepping-stone in the growing sense of colonial unity.

Colonial Interpretation of and Reactions to the Tea Act: The Boston Tea Party

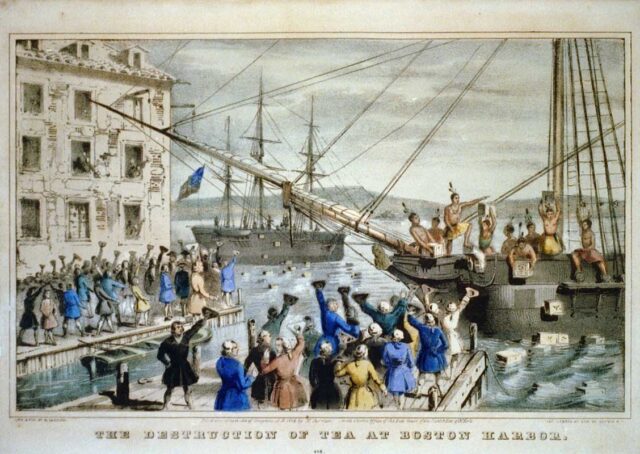

1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier was entitled “The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor”; the phrase “Boston Tea Party” had not yet become standard. Contrary to Currier’s depiction, few of the men dumping the tea were actually disguised as Native Americans. / Boston Public Library

Now it was at this moment that Lord North passed the Tea Act. It actually had less to do with the colonies than it had to do with a miserably timed necessity. North was trying to save the East India Tea Company from collapse. The Tea Act of 1773 removed import duties on East India tea, which basically made British tea cheaper than Dutch tea, in the hope that this would inspire colonists to purchase British tea. Okay. So you would think and certainly you can understand why Lord North would think that this would make the colonists happy because he is lowering duties on tea. The East India Company hopefully, as he’s thinking, would be solvent, maybe the Townshend Act, my little tea tax left in place there, is going to matter less because I’ve just lowered duties on some tea, so maybe now the colonists will pay the tea tax, Parliament will obviously have the right to tax the colonies in their eyes, and maybe this will actually quiet things a little.

But once again the British government misjudged the colonial reaction — again showing how you have different evolving mindsets here and they’re not necessarily, either one, understanding what’s happening in the other case. So the colonists not surprisingly had their own interpretation of the act. They actually felt that the act was granting a monopoly to the East India Tea Company, enforcing the control of the British government over what they felt like was supposed to be free trade, so maybe in the future the British would begin to control the importation of other goods as well.

Okay, so somewhat paradoxically by reducing the duty on English tea, North helped fuel colonial fears that there was a plot in England against colonial rights — which inspired the colonists to imagine the worst immediately when a suspicious act was passed. So: ‘oh, this must be part of that plot, this Tea Act. Yes, he may seem to be lowering the duty on tea. There must be another motive. Ah, they must be trying to control our trade.’ You can sort of see on both sides how the logic makes sense. You can also see how this is a problem.

As with the Stamp Act, colonists responded by pinpointing the people who would be distributing the tea, right? So first, you didn’t want to be a stamp agent; now you don’t want to be a person selling tea. So they pinpointed the merchants who were selling tea and they pressured them not to sell it. And broadsides were posted in public places to inform and involve the populace, saying things like: “Friends! — Brethren! — Countrymen — that worst of plagues, the detested TEA, shipped for this port by the East-India Company, is now arrived in this Harbour; the Hour of Destruction, or manly opposition to the Machinations of Tyranny, stares you in the face.” It’s a big drama. These are not people who do things halfway: destruction — staring you in the face — tyranny — manly opposition.

Portrait of Thomas Hutchinson, Massachusetts Colonial Royal Governor, by Edward Truman, 1741 / Massachusetts Historical Society

So when ships loaded with tea began arriving in major colonial ports, obviously things become more heated. In some cities the tea was just unloaded and then locked up in a warehouse and left there, not sold. In Philadelphia and New York they actually kept these ships with tea on them out away from the harbor, so that they just never came in close to shore. However, in Boston Governor Hutchinson decided to force the issue, in his mind as a means of protecting British sovereignty in the colonies. So Hutchinson ordered the tea ships to be unloaded.

Okay. So we have an eyewitness account of someone who heard the response to that announcement, who heard what happened when it — people heard that Hutchinson was going to ask for the tea to be unloaded and it was at a Boston town meeting: December 16, 1773. Basically, people knew that there was this tea-bearing ship in the harbor, and they knew that on December 16, in the evening, the captain of that ship was going to go to the town meeting and tell the town meeting — Samuel Adams who was chairing the meeting — what was going to happen with the tea. People knew that, and thus there was an enormous crowd gathered outside of the Old South Church where the meeting was being held to see what would happen. Right? So everyone knows this is the stare-down. Okay. What’s going to happen? Is the tea coming off the boats? And if the tea’s coming off the boats, what happens next? Big crowd, and here’s what this eyewitness heard as the crowd learned that Hutchinson was insisting on the unloading of the tea.

So this eyewitness, he’s at home drinking tea when he said, I heard “such prodigious shouts. . . that induced me, while drinking tea at home, to go out and know the cause of it. The [meeting] house was so crowded I could get no farther than the porch …You’d [have] thought that the inhabitants of the infernal regions had broke loose. For my part, I went contentedly home and finished my tea.” [laughter] What’s going on? I got to go finish my tea. [laughs] “But was soon informed what was going forward.” Right? Is soon told they’re going to unload the tea, “but still not crediting it without ocular demonstration” [laughs] okay, eighteenth century: I wanted to see it for myself, right? But not crediting it without “ocular demonstration,” I went to watch.

Okay. So our eyewitness goes off to get ocular demonstrations of the unloading of the tea, but what he ends up watching is an assemblage of somewhere between thirty and sixty men disguised as Indians aboard three ships on Griffin’s Wharf, and these men basically worked on those ships for several hours and threw 342 chests of tea over the side. A huge number of people watched from the docks and, as I mentioned before when I was talking about the Stamp Act, riots and popular demonstrations were kind of a regular part of the system in the colonies. Riots were not normally chaotic moments of violence and disorder unless you were shingle-by-shingle taking apart [laughs] the house of the stamp agent for example, but usually they were almost ritualized demonstrations of protest.

So what we have here is not a wild riot on these ships. Protestors were so careful not to do anything other than make their point, not to do anything other than destroy tea, that allegedly they brought a locksmith with them to open locks or repair locks that were broken. These are people who understand property rights. Right? ‘We value property. We don’t want to break your locks.’ They’re not actually out to get the ship owners; they just want the tea. So they actually were very orderly about the way in which they went to destroy the tea.

So to give us a sense of what happened, I’m going to use an account by another man. His name is George Hughes. He actually helped destroy the tea, so he’s one of the people throwing chests of tea over the side. And in his account, Hughes says that back at the Old South Church, the announcement that Hutchinson was going to order the unloading of the tea led to, quote, “a general huzzah for Griffin’s Wharf.” A huzzah is an eighteenth-century hooray: ‘hooray, off to Griffin’s Wharf.’ So these guys were like: You’re going to unload the tea? We’re there [laughs] and something bad is going to happen.

So Hughes, a participant in what would come to be known — but not until well into the nineteenth century — as the Boston Tea Party, continues his account. He says, “It was now evening, and I immediately dressed myself in the costume of an Indian equipped with a small hatchet. . . with which and a club, after having painted my face and hands with coal dust in the shop of a blacksmith, I repaired to Griffin’s Wharf where the ships lay that contained the tea,” and Hughes is ordered to go to the captain and “demand of him the keys to the hatches” because they don’t want to damage the ship, “and a dozen candles” so that they can see what they’re doing. [laughs] Right? Just being very sort of polite here. “The captain promptly replied and delivered the articles but requested me at the same time to do no damage to the ship or rigging.” So these Indians cut and split the tea chests with their tomahawks and threw them overboard. There were some people who tried to climb on board the ship to scoop up tea to take back home with them. This was not a wise thing to do because they were caught and their hats and wigs were dumped in the water with the tea and they were kicked away, literally. The crowd sort of just kicked them away from the ships on the wharf.

So Hughes concludes his account by saying, “We then quietly retired to our several places of residence, without having any conversation with each other or taking any measures to discover who were our associates,” right? Because they’re all disguised.”

“Nor do I recollect of our having had the knowledge of the name of a single individual concerned in the affair. . . . There appeared to be an understanding that each individual should volunteer his services, keep his own secret, and risk the consequences for himself. No disorder took place during that transaction, and it was observed at that time that the stillest night ensued that Boston had enjoyed for many months.”

So, not wild abandon. It’s a pretty controlled riot.

British Dismantling of Colonial Governance and Conclusion

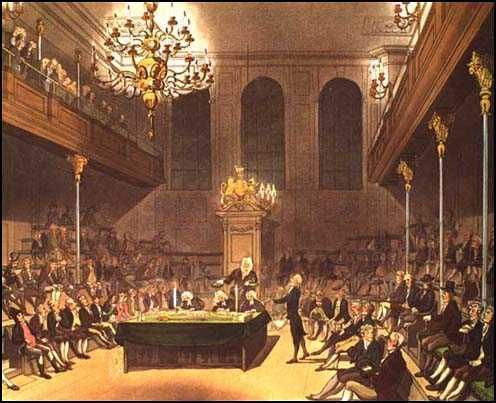

Illustration of British Parliament in 1764 / British Library

However, Lord North was dumbfounded because he really thought he had given the colonies what he called a “relief” instead of an oppression, and he assumed that only what he called, quote, “New England fanatics” would have rebelled against his measure. So this event, this tea event in Boston, is proof to him that the issue no longer is one of taxation but now this appears to him to be more about whether Britain had any authority over, quote, “the haughty American republicans at all.”

And this is an actual transcription of part of the parliamentary debate over what to do after this was discovered. North said,

“The Americans have tarred and feathered your subjects, plundered your merchants, burnt your ships, denied all obedience to your laws and authority; yet so clement and so long forbearing has our conduct been, that is — it is incumbent on us now to take a different course. Whatever may be the consequence, we must risk something. If we do not all is over.”

And another Member of Parliament said he thought, quote, “The town of Boston ought to be knocked about their ears and destroyed.” [laughter] Okay. “I am of opinion you will never meet with that proper obedience to the laws of this country until you have destroyed that nest of locusts.” Okay. Boston is not popular in Parliament. Another member said — we’re moving back in to arrogant British quotation territory —

Lord North could not do “a better thing than to put an end to their town meetings. I would not have a man of a mercantile cast every day collecting him — themselves together, and debating about political matters. I would have them follow their occupations as merchants, and not consider themselves as ministers of that country. . . . You have, Sir, no government, no governor, the whole are the proceedings of a tumultuous and riotous rabble, who ought, if they had the least prudence, to follow their mercantile employment, and not trouble themselves with politics and government, which they do not understand.”

Dr. Joanne Freeman

Okay. Go back to your regular jobs, guys. Don’t mess in government. What are they doing? Why are they doing this? They’re merchants. They’re not politicians, and look what they’re doing. They’re messing up the imperial system.

The result of that kind of sentiment would be the passage of four acts that Americans termed the Intolerable Acts, passed in Parliament in the spring of 1774. And I’m so on the cusp of running out of time. I think what I will do is pause there since we’re just about out of time for class. We will continue. We will add the details of the Intolerable Acts and then move in to the logic of resistance, which is going to look at how this is adding up to an ongoing logic in the colonial mindset.

Written by Dr. Joanne Freeman, Professor of History and American Studies, Yale University for Brewminate ~ January 28, 2017, transcribed from a lecture which she originally gave February 2, 2010.