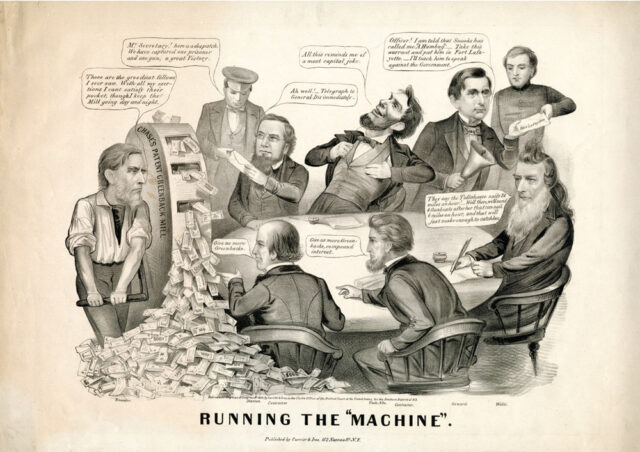

The Union’s financial success depended on military success. As presidential aide John Hay wrote in an anonymous newspaper article in January 1862 when any movement by the Union Army was stalled: “The Secretary of Finance has displayed wonderful zeal and ability in filling a bankrupt treasury and supplying the sinews of war. In this respect, Mr. Chase has accomplished a herculean task, but all his plans and efforts will end in ruin unless followed by wholesome legislative enactments and decided military movements. Already the treasury notes have commenced to depreciate, and a few months of Congressional and military inaction, they will sink to a level with the old Continental Scrip or the assignats of the French Revolution.”

The price of gold was very fluid. Reuben A. Kessel and Armen A. Alchian wrote: “Abandonment of the gold standard, while the major trading countries of the world remained on this standard, made the price of foreign exchange a function of the price of gold, or, to use the language of the times, the premium on gold. Inconvertible fiat money, referred to popularly as ‘greenbacks’ and officially as ‘United States notes,’ were issued as a means of war finance and became the currency of the times (except in California and Oregon). As a result, the price of gold as measure in greenbacks determined the cost of foreign exchanged. The free-exchanged rate eliminated the development of foreign-exchange ‘shortages,’ and the magnitude of the foreign-exchange problem of the North was largely unrecognized both then and now.”

The price of gold during the Civil War reflected the Union’s military success or lack of it. Historian William F. Hixson wrote that “the hoarding of gold began even before Lincoln’s inauguration and before the outbreak of war. The demands by hoarders on banks for the banks’ gold reserves mounted relentlessly thereafter.”

Passage of the Legal Tender Acts in early 1862 increased the speculation in gold. “The gold exchange had been established shortly after the depreciation of legal tenders had set in, and dealing in gold, a necessity for the merchant and importer after the currency no longer commanded its face value in gold, soon attracted speculators,” wrote Henrieta Larson. A decade after the Civil War ended, James K. Medbery described the gold room’s operations: “The gloom or the gladness over success or defeat of the national flag mingled with individual passions. Men leaped upon chairs, waved their hands, or clenched their fists; shrieked, shouted; the bulls whistled ‘Dixie,’ and the bears sung ‘John Brown’; the crowd swayed feverishly from door to door, and, as the fury mounted to white heat, and the tide of gold fluctuated up and down in rapid sequence, brokers seemed animated with the impulses of demons, hand-to-hand combats took place, and bystanders, peering through the smoke and dust, could liken the wild turmoil only to the revels of maniacs.”

Medbery wrote: “When the banks of the Union refused to honor their own bills by payment in coin for the full face value, gold tremulously vibrated in small percentages for months before it began that succession of immense leaps which grew out of the first reverses of the war. On Saturday, April 18,1862, it was at 101; July 1 it was 108; July 21 it stood at 120. The disastrous campaign of the Peninsula had borne fruit! The houses in foreign trade who had bills for one hundred thousand dollars maturing found that it would require twenty thousand more to make their contracts good. It was their first contact face to face with the luxury of rebellion. New York, neither in its commerce nor its speculation, looked kindly upon the appreciation of bullion. At the Stock Exchange the bears were in scores and the bulls in half-dozens. It was the gentlemanly thing to sell gold, and the stock operators chose to be gentlemen. In his Annual Treasury Report at the end of 1862, Secretary Chase wrote:

It is true that gold commands a premium in notes; in other words, that to purchase a given amount of gold a greater amount in notes is required. But it is also true that, on the suspension of specie payments and the substitution for coin of United States notes, convertible into six per cent specie bonds as the legal standard of value, gold became an article of merchandise, subject to the ordinary fluctuations of supply and demand, and to the extraordinary fluctuations or mere speculation. The ignorant fears of foreign investors [sic] in national and State bonds and other American securities, and the timid alarms of numerous nervous individuals in our country, prompted large sacrifices upon evidences of public and corporate indebtedness in our markets, and large purchases of coin for remittance abroad or hoarding at home. Taking advantage of these and other circumstances tending to an advance of gold, speculators employed all the arts of the market to stimulate that tendency and carry it to the highest point. This point was reached on the 15th day of October. Gold sold in the market at a premium of 37 5/8 percent.

Both greed and subversion were at work. Historian Allan Nevins noted that “gold gambling became a favorite occupation of some Peace Democrats and quasi-traitors. Letters of Confederate agent intercepted in 1863 revealed that Southern leaders were nearly as well pleased when their Copperhead friends forced the price of gold up as when their generals threw [William] Rosecrans or [George] Meade back. One Senator who accepted the treasonable character of speculators declared: ‘Gold gamblers as a class are disloyal men in sympathy with the South.’ Most of them were probably only in sympathy with their pocket nerves.” Cooke biographer Henrieta Larson noted that “Jay Cooke regarded the gold speculator as a rebel and used all the force of his publicity to discredit him.” In his memoirs, Cooke observed: “The city of New York, whilst containing, during war times, many noble and patriotic citizens and institutions, was undeniably the centre and very hotbed of Southern sentiment and scheming. Being filled with foreigners and the great place of rendezvous of the secret emissaries of the South and disloyal politicians, it became the centre of speculation in gold and every species of material and produce which could be turned into gold by trans-shipment abroad. This speculation and the rise in the price of specie were so persistent and continuous that even many good citizens thoughtlessly entered the trade and thus contributed to the depreciation of our bonds and currency, and to the increase of the cost of living of our soldiers and their families. The editors I employed were instructed to make constant warfare upon this speculative disposition and to portray the want of patriotism of those engaged in it. Articles were constantly written and published revealing the effect of such speculation, and calling upon all good citizens to refrain from engaging therein. The result of these efforts was of course important and in consequence of the articles many refrained from indulgence in so tempting a field of speculation.” Financial historians William Schultz, and M. R. Caine wrote: “While the Union Treasury was well aware of the dangerous powers exercised by the New York speculators, it hesitated to thwart them openly. Overt action upon its part might be distorted and interpreted as a confession of weakness…On occasions when the two [Chase and Cooke] believed that the hostile speculators had pushed their attack on the dollar too far, Cooke and his associates would raid, reinforced by the release of gold from the Union Treasury.”

Both greed and subversion were at work. Historian Allan Nevins noted that “gold gambling became a favorite occupation of some Peace Democrats and quasi-traitors. Letters of Confederate agent intercepted in 1863 revealed that Southern leaders were nearly as well pleased when their Copperhead friends forced the price of gold up as when their generals threw [William] Rosecrans or [George] Meade back. One Senator who accepted the treasonable character of speculators declared: ‘Gold gamblers as a class are disloyal men in sympathy with the South.’ Most of them were probably only in sympathy with their pocket nerves.” Cooke biographer Henrieta Larson noted that “Jay Cooke regarded the gold speculator as a rebel and used all the force of his publicity to discredit him.” In his memoirs, Cooke observed: “The city of New York, whilst containing, during war times, many noble and patriotic citizens and institutions, was undeniably the centre and very hotbed of Southern sentiment and scheming. Being filled with foreigners and the great place of rendezvous of the secret emissaries of the South and disloyal politicians, it became the centre of speculation in gold and every species of material and produce which could be turned into gold by trans-shipment abroad. This speculation and the rise in the price of specie were so persistent and continuous that even many good citizens thoughtlessly entered the trade and thus contributed to the depreciation of our bonds and currency, and to the increase of the cost of living of our soldiers and their families. The editors I employed were instructed to make constant warfare upon this speculative disposition and to portray the want of patriotism of those engaged in it. Articles were constantly written and published revealing the effect of such speculation, and calling upon all good citizens to refrain from engaging therein. The result of these efforts was of course important and in consequence of the articles many refrained from indulgence in so tempting a field of speculation.” Financial historians William Schultz, and M. R. Caine wrote: “While the Union Treasury was well aware of the dangerous powers exercised by the New York speculators, it hesitated to thwart them openly. Overt action upon its part might be distorted and interpreted as a confession of weakness…On occasions when the two [Chase and Cooke] believed that the hostile speculators had pushed their attack on the dollar too far, Cooke and his associates would raid, reinforced by the release of gold from the Union Treasury.”

The price of gold remained unstable through 1864. Paul Studenski and Herman Edward Krooss explained that “the price of gold was affected by the news from the military front, the ebb and flow of imports payable in gold, and the government’s gold payment of interest on its bonds. Bad news caused gold to be hoarded and its price in terms of paper to rise, while good news caused gold to be thrown on the market and its price to drop.” Wall Street naturally hedged its bets. Greenbacks helped stabilize the banking system and the economy. In the wake of the Legal Tender Act, noted Allan Nevins, “inflation brought about in part by the use of greenbacks was generally applauded by financial interests. The activity which money encourages is the secret of our prosperity,’ observed the American Railroad Journal.” John Steele Gordon wrote: “The creation of a second form of money…set off a wild speculative bubble in Wall Street as the value of the greenback in terms of gold gyrated in response to Union victories and defeats. In July, 1863, just before Gettysburg it took fully 287 greenback dollars to buy 100 gold ones. The speculators were called ‘General Lee’s left wing in Wall Street’ in the newspapers, and Lincoln publicly wished that ‘every one of them had his devilish head shot off.’ But the opprobrium affected their speculations not a bit.”

Congressional efforts to stymie gold speculation were themselves stymied. Historian John Steele Gordon wrote: “While the federal government required that greenbacks trade at par with gold, that simply didn’t comport with economic reality, and the law was ignored. The New York Stock and Exchange Board quickly began trading gold. But because, not surprisingly, the price of gold, as measured in greenbacks, tended to fluctuate inversely with the fortunes of the Union Army, the exchange banned the trading the next year as unpatriotic.” Gordon wrote: “The curb brokers, who traded stocks out on Broad Street, then organized a place called Gilpin’s News Room (although it is not quite clear who Gilpin was) in which to trade gold. Anyone willing to pay an annual $25 fee was welcome to trade there.” Respectable merchants who needed gold for business purposes or to hedge against fluctuations in the price of greenbacks used Gilpin’s, as did the hundreds of pure speculators hoping to make a fortune out of the vicissitudes of a war being fought for their country’s very existence.” Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Gold fluctuations and speculation thereon were irrepressible once the country left a specie basis, and no more censurable in themselves than the fluctuations of the grain and livestock markets. But they aroused indignation when gold gambling became a favorite occupation of some Peace Democrats and quasi-traitors.” Assistant presidential secretary William O. Stoddard, who speculated often and recklessly in gold and stocks, reminisced: “Does the President take any interest in Wall Street gambling operations? Of course he does, for the currency is the life of his policy. He was talking about it at the dinner-table yesterday, when we were there. We must go right over now, and hand him that paper.”

Congressional efforts to stymie gold speculation were themselves stymied. Historian John Steele Gordon wrote: “While the federal government required that greenbacks trade at par with gold, that simply didn’t comport with economic reality, and the law was ignored. The New York Stock and Exchange Board quickly began trading gold. But because, not surprisingly, the price of gold, as measured in greenbacks, tended to fluctuate inversely with the fortunes of the Union Army, the exchange banned the trading the next year as unpatriotic.” Gordon wrote: “The curb brokers, who traded stocks out on Broad Street, then organized a place called Gilpin’s News Room (although it is not quite clear who Gilpin was) in which to trade gold. Anyone willing to pay an annual $25 fee was welcome to trade there.” Respectable merchants who needed gold for business purposes or to hedge against fluctuations in the price of greenbacks used Gilpin’s, as did the hundreds of pure speculators hoping to make a fortune out of the vicissitudes of a war being fought for their country’s very existence.” Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Gold fluctuations and speculation thereon were irrepressible once the country left a specie basis, and no more censurable in themselves than the fluctuations of the grain and livestock markets. But they aroused indignation when gold gambling became a favorite occupation of some Peace Democrats and quasi-traitors.” Assistant presidential secretary William O. Stoddard, who speculated often and recklessly in gold and stocks, reminisced: “Does the President take any interest in Wall Street gambling operations? Of course he does, for the currency is the life of his policy. He was talking about it at the dinner-table yesterday, when we were there. We must go right over now, and hand him that paper.”

There is a peculiarly humorous expression on his face, as he looks up.

“What is the price of gold this morning? Is it going up or down?”

“Up, Mr. Lincoln. The Street is wild.”

“Well, now, they don’t know everything. If I were a bear on Wall Street, and if I were short of gold, I’d keep short. It’s a good time to sell.”

“He never gives any explanations, but he adds something bitter about bulls that may be tossed themselves, and we will go back to work.”

“Is that not one of the most remarkable looking men you ever saw? The tall hawk-eyed man, who cannot stand still, but keeps on walking, walking, up and down the room. He is saying something to himself aloud…”

“I’ll stop, right where I am! If it goes on up, it’ll break me!”

“What’s the matter, Dr. [Thomas] Durant?”

“Short of gold! Sold my head off! And now it’s just booming. Time for me to take in, I guess, and stand my losses just as they are.”

“Now, Dr. Durant, they don’t know everything. If I were a bear on Wall Street, and if I were short of gold, I’d keep short. It’s a good time to sell.”

“Is that so? Can you send a telegram from here, for me? Give me a blank!”

Telegram after telegram is dashed off rapidly by the relieved bear, and a messenger carries them out after him. It is to be hoped that the price of gold will drop heavily, for he needs all his money and credit. He is undertaking to build the Pacific Railroad, and to save the Pacific slope to the Union. As to the President’s unintentional suggestion, no other such instance has occurred or probably ever will. Nothing done in or about the White House has anything to do with the course of things on Wall Street. The results of battles are known in New York even before they are in Washington, only that the reports received there, never tally with those received by the War Office. The President and the Secretary of War would be ruined if they should attempt to play bulls and bears upon the strength of any dispatches sent them by the generals.

Stoddard’s own gold speculations embarrassed the White House. He had an illicit relation with Clinton Rice, a Wall Streeter who benefitted from the advance political information he obtained from Stoddard in order to gauge their possible impact on financial instruments. Stoddard later admitted: “Stock and gold gambling was the mania of the day, and for a time I had it very badly, but I made no concealment of it, for I thought [it] no evil.” Stoddard’s speculative behavior annoyed fellow presidential aide John Hay who noted in October 1864, that Stoddard had sent him “a more than usually asinine letter…pretending he is working for the election” when he was really “in New York stock jobbing.”

“In February, 1863, Congress attempted to put a curb upon the gold gamblers. It was made penal to offer loans on bullion above par. Other fribbling difficulties’ were thrown in the way of traffic in coin; but the quotations were in no wise seriously affected. Gold fell and rose between 172 and 145 until July. The capture of Fort Wagner, and the strong belief that Charleston would fall into the hands of the Union, were the first vital blows to the Washington clique and their New York coadjutors. The precious metal reached 122 before it rebounded.” Financial Historian Henry Crosby Emery wrote: “Only one attempt has been made by Congress to suppress speculation. As soon as the paper currency of the Civil War became depreciated, speculation in gold became active, and the ups and downs in the price of gold, in other words the fluctuations in the amount of discount on the greenbacks, were regarded with the same indignation with which European governments had in former years viewed the fluctuations in the value of the public stock. In both cases the evil was attributed solely to the machinations of the speculator. In 1863 an act was passed which placed a tax of one-half per cent, on all sales of gold for delivery after a period exceeding three days; and provided that any loan of currency against gold coin in excess of the amount of coin should be void.”

The key factor in gold market movements was information about the war. Washingtonians vied to get early information about military successes or failures. Contemporary James K. Medbery wrote: “The gambling instinct penetrated to the national capital, and soon made that the point d’apus for all operations. The Washington Party, as it was styled, held the keys to the gold citadel. Members of both Houses, and of all political creeds, resident bankers, the lobby agents, clerks, and secretaries haunted the War Department for the latest news from the seat of war. The daily registry of the Gold Room [in New York] was a quicker messenger of the successes or defeats than the tardier telegrams of the Associated Press.” Speculation, however, carried with it a tint of disloyalty. Historian Heather Cox Richardson wrote: “Speculation…had political repercussions, actively hurting the war effort by depreciating greenbacks and Union bonds, thus weakening Union credit. This political aspect of gold trading tainted speculators with disloyalty to the government. It could only hurt their reputation that the Gold Room, the center of New York gold trading, received heavy ‘bull’ orders from Washington, Baltimore, and Louisville, Kentucky, all of which were close to the South and associated with strongly secessionist operators. One veteran of the Gold Room remembered that Southerners frequented the exchange. Having watched Confederate currency plummet, they had come North to cash in when greenbacks did the same. Union victories sent gold down, Confederate victories did the opposite, and news from the battlefields could turn the Gold Room into ‘a den of wild beasts.’”

The key factor in gold market movements was information about the war. Washingtonians vied to get early information about military successes or failures. Contemporary James K. Medbery wrote: “The gambling instinct penetrated to the national capital, and soon made that the point d’apus for all operations. The Washington Party, as it was styled, held the keys to the gold citadel. Members of both Houses, and of all political creeds, resident bankers, the lobby agents, clerks, and secretaries haunted the War Department for the latest news from the seat of war. The daily registry of the Gold Room [in New York] was a quicker messenger of the successes or defeats than the tardier telegrams of the Associated Press.” Speculation, however, carried with it a tint of disloyalty. Historian Heather Cox Richardson wrote: “Speculation…had political repercussions, actively hurting the war effort by depreciating greenbacks and Union bonds, thus weakening Union credit. This political aspect of gold trading tainted speculators with disloyalty to the government. It could only hurt their reputation that the Gold Room, the center of New York gold trading, received heavy ‘bull’ orders from Washington, Baltimore, and Louisville, Kentucky, all of which were close to the South and associated with strongly secessionist operators. One veteran of the Gold Room remembered that Southerners frequented the exchange. Having watched Confederate currency plummet, they had come North to cash in when greenbacks did the same. Union victories sent gold down, Confederate victories did the opposite, and news from the battlefields could turn the Gold Room into ‘a den of wild beasts.’”

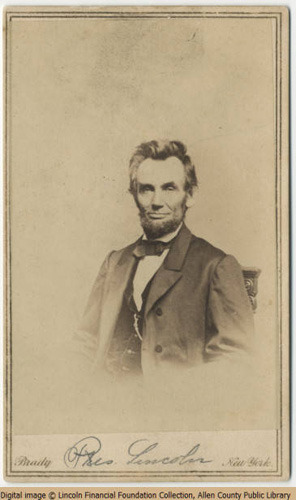

President Lincoln hated gold speculation. Artist Francis B. Carpenter recalled a conversation with President Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin: “The bill empowering the secretary of the Treasury to sell the surplus gold had recently passed, and Mr. Chase was then in New York, giving his attention personally to the experiment. Governor Curtin referred to this, saying, ‘I see by the quotations that Chase’s movement has already knocked gold down several per cent.’ This gave occasion for the strongest expression I ever heard fall from the lips of Mr. Lincoln. Knotting his face in the intensity of his feeling, he said, ‘Curtin, what do you think of those fellows in Wall Street, who are gambling in gold at such a time as this?’ ‘They are a set of sharks,’ returned Curtin. ‘For my part,’ continued the President, bringing his clinched hand down upon the table, ‘I wish every one of them had his devilish head shot off!’” Carpenter wrote: “When Mr. Lincoln handed to his friend Gilbert his appointment as assessor in the Wall Street district, New York, he said: ‘Gilbert, from what I can learn, I judge that you are going upon good ‘missionary’ ground. Preach God and Liberty to the ‘bulls’ and ‘bears,’ and get all the money you can for the government.”

President Lincoln hated gold speculation. Artist Francis B. Carpenter recalled a conversation with President Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin: “The bill empowering the secretary of the Treasury to sell the surplus gold had recently passed, and Mr. Chase was then in New York, giving his attention personally to the experiment. Governor Curtin referred to this, saying, ‘I see by the quotations that Chase’s movement has already knocked gold down several per cent.’ This gave occasion for the strongest expression I ever heard fall from the lips of Mr. Lincoln. Knotting his face in the intensity of his feeling, he said, ‘Curtin, what do you think of those fellows in Wall Street, who are gambling in gold at such a time as this?’ ‘They are a set of sharks,’ returned Curtin. ‘For my part,’ continued the President, bringing his clinched hand down upon the table, ‘I wish every one of them had his devilish head shot off!’” Carpenter wrote: “When Mr. Lincoln handed to his friend Gilbert his appointment as assessor in the Wall Street district, New York, he said: ‘Gilbert, from what I can learn, I judge that you are going upon good ‘missionary’ ground. Preach God and Liberty to the ‘bulls’ and ‘bears,’ and get all the money you can for the government.”

Nicolay and Hay wrote: “Gold, having been driven from circulation by the legal-tender notes, became at once the favorite commodity for speculation in Wall street, and while the premium upon it rose to a certain extent in proportion to the increase of the volume of paper money, and was subject to violent fluctuations in consequence of military successes or disasters, there was no such method in the course of its quotations as to render them explicable by either of these influences. It had become, so to speak, a fancy stock, and there was no more reason for its wilder fluctuations than for those of other securities which rise and fall in obedience to the currents of Wall street and without reference to intrinsic values. Just before the passage of the legal-tender bill the premium upon gold was 4 3/8 per cent., and shortly after it became a law the premium fell to 1; but it gradually rose until in the middle of July it was 17, in the middle of October 32, and at the end of the year 34. On the 25th of February, 1863, after the legal-tender law had been in operation for a year, the premium on gold had risen to 72; the brilliant successes of the National cause at Gettysburg and Vicksburg reduced it to 23; it rose again in October to 56 3/8, and rose no higher than that until the following spring, when on the 14th of April, 1864, it was quoted at 88, and on the 22nd of June, as the consequence of an ill-advised bill passed by Congress to prevent speculation in gold, the premium climbed at once to the frightful altitude of 130, falling the day afterwards to 115. On the 1st of July it jumped to 185, on the 2d it fell back to 130, and on the 6th the unfortunate law, born of a short-sighted patriotism, was repealed.”

In the first half of 1864 Chase tried to use his personal influence to calm the market. John Niven wrote: “By early 1864 greenback currency has depreciated significantly in terms of gold and speculation in precious metals was rampant. Chase saw clearly that the precipitous decline in value of greenback dollars was due to uncertainties in the financial communities about the fate of the Union and consequently its public credit. Something approaching parity between the fiat currency and gold could be achieved only through Union victories that made peace certain and an adequate program of taxation to meet the costs of the war.”

Despite his own accurate appraisal, Chase intervened in the gold market in early 1864 to curb speculation and stabilize greenback currency. After visiting New York in April, Chase observed:

“I have just come from New York where my arrival was most opportune. Had I stayed away, gold would certainly have gone to $200 and over, and we should have had a had a terrific panic. A little judicious use of the exchange I so fortunately had in London and other points has made the speculators look glum, and had not the disaster at Fort Pillow provoked discouraging forebodings and disloyal misrepresentations, gold would have gone down today to only $165. As it is, the change is very favorable.”

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, another hard money man, wrote in his diary on April 15, 1864: “The gold panic has subsided, or rather abated. Chase is in New York. It is curious to see the speculator’s conjectures and remarks on the expedients and subterfuges that are resorted to. Gold is truth. Its paper substitute is a fiction, sustained by a public confidence in part because there is a belief that it will ultimately bring gold, but it has no intrinsic value and the great increase in quantity is undermining confidence.” The next day, Welles wrote:

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, another hard money man, wrote in his diary on April 15, 1864: “The gold panic has subsided, or rather abated. Chase is in New York. It is curious to see the speculator’s conjectures and remarks on the expedients and subterfuges that are resorted to. Gold is truth. Its paper substitute is a fiction, sustained by a public confidence in part because there is a belief that it will ultimately bring gold, but it has no intrinsic value and the great increase in quantity is undermining confidence.” The next day, Welles wrote:

“There is still much excitement and uneasy feeling on the gold and currency question. Not a day but that I am spoken to on the subject. It is unpleasant, because my views are wholly dissimilar from the policy of the Treasury Department, and Chase is sensitive and tender – touchy, I may say – if others do not agree with him and adopt his expedients. Mr. Chase is now in New York. He has directed the payment of the May interest, anticipating that throwing out so much gold will affect the market favorably. It will likely to have that effect for a few days but is no cure for the evil. The volume of irredeemable paper must be reduced before there can be permanent relief. He attributes to speculators the rise in gold. As well charge the manufacturers with affecting the depth of water in the rivers, because they erect dams across the tributaries! Yet one cannot reason with our great financier on the subject. He will consider it a reflection on himself personally and claims he cannot get along successfully if opposed.”

For a brief period in 1864, Congress prohibited the buying and selling of gold outside of brokers, but the price of gold as measured in greenbacks jumped. John Steele Gordon wrote that in 1864, “several members of the Wall Street establishment… established the New York Gold Exchange. The trading floor featured a large clocklike dial with a single hand that indicated the current price of gold. While it had higher standards and better enforced rules than Gilpin’s (which quickly shut down), the New York Gold Exchange was still no place for the fainthearted.”

Financial Historian Henry Crosby Emery noted: The Anti-Gold Futures Act of 1864, was passed June 17. It was entitled ‘An Act to prohibit certain Sales of Gold and Foreign Exchange.’ It forbade all contracts for the sale or purchase of gold coin or bullion for delivery on any day subsequent to the day of the contract, also all contracts for the sale of gold which was not actually in the possession of the seller at the time of contract. Contracts in violation of these provisions were declared void; and such violation was made a misdemeanor with a penalty of fine or imprisonment. The act also forbade all sales not made at the ordinary place of business of one of the contracting parties. This provision was in order to close up the Gold Room where this trading was done. The expectation of Secretary Chase and of Congress, that this act would abolish the premium on gold, was not fulfilled. Gold jumped from 198 to 250.” On July 2d, two weeks after its enactment, the statute was repealed.” Allan Nevins wrote: “This enactment proved totally abortive. After a wild market dance and general rise, it was shamefacedly repeated. Then the Union victories in late summer helped to place the quotations on a downward trend, and public uneasiness abated.”

NOTE: The Anti-Gold Futures Act of 1864 (13 Stat. 132) was the first instance of United States Federal regulation of derivatives. More formally titled “An Act to Prohibit Certain Sales of Gold and Foreign Exchange,” the Act was passed by Congress on June 17, 1864. ~ Ed.

It was a response to Congressional perceptions that the low value the fiat currency greenbacks were then trading at relative to gold was as a result of a failure of the private market. The Act prohibited the trading of gold futures, and also criminalized the sale of foreign exchange more than ten days in the future. Congress’s action was followed by a further sharp drop in the value of the greenbacks. Two weeks later Congress repealed the act.[1]

Historian James Ford Rhodes noted that on June 17, 1864:

“The President approved an act of Congress which aimed to prevent speculative sales of gold and proved about as effectual as human efforts to stay the flood. After this enactment the speculation became wilder than before and, owing to the military failures and Chase’s resignation as Secretary of the Treasury, gold touched on the last day of June 250. On July 2 the act intended to prevent speculation in gold was repealed. On July 11, when Early was before Washington and communication with that city had been cut, gold fetched 285, its highest price during the war; next day, the day of the skirmish near Fort Stevens and of the rumor in Philadelphia that the capital had fallen, it sold at 282. Such prices meant that the paper money in circulation was worth less than forty cents on the dollar. As the Government bonds were sold for this money, the United States were paying, with gold at 250 (at which price or higher it sold during the greater part of July and August), fifteen per cent on their loans. Nevertheless money could be had…Business, though feverish, was good; and many fortunes of our day had their origin in these excited business years of 1863 and 1864; when sales were easily made, most transactions were for cash, and nearly everyone engaged in trade or manufactures seemed to be getting rich. There must have been still considerable financial strength in reserve and, as the value of property depended largely on a stable government, ample funds for its maintenance would have been forthcoming in a supreme crisis. Even now, an element of confidence was to be seen in the large and constant purchases of our bonds by the Germans.

During the presidential campaign in the autumn of 1864, bluff and cantankerous General Benjamin F. Butler ruled New York City to insure that there was no violence. Just before the election, Butler wrote Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that conspirators “propose to raise the price of gold so as to affect the necessaries of life, and raise discontent and disturbance during the winter, declare then that they are cheated in the election by military interference and fraudulent ballots, and then inaugurate McClellan.” Butler wrote that is was “certain… that the gold business is in the hands of a half dozen firms who are all foreigners or secessionists, and whose names and descriptions I will give you.” The general, who had a tendency to see conspiracies and villains wherever he was posted, wrote:

During the presidential campaign in the autumn of 1864, bluff and cantankerous General Benjamin F. Butler ruled New York City to insure that there was no violence. Just before the election, Butler wrote Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that conspirators “propose to raise the price of gold so as to affect the necessaries of life, and raise discontent and disturbance during the winter, declare then that they are cheated in the election by military interference and fraudulent ballots, and then inaugurate McClellan.” Butler wrote that is was “certain… that the gold business is in the hands of a half dozen firms who are all foreigners or secessionists, and whose names and descriptions I will give you.” The general, who had a tendency to see conspiracies and villains wherever he was posted, wrote:

“You are probably aware that the Government has sold ten (10) or twelve millions (12,000,000 of gold) within the past twenty (20) days. The Secretary of the Treasury will tell you how much, it is none of my business to know – but one firm, H. J. Lyons & Co., have bought and actually received in coin by confession to me more than ten millions (10,000,000) within the past fortnight, and his firm is now carrying some three millions (3,000,000) of gold. I felt bound to look up the case of Gentlemen H. J. Lyons and Co. I sent for Lyons, although I suppose I had no right to do so, wanting territorial jurisdiction, set him down before me and examined him. His story is, as I made him correct it by appealing to my own investigations, as follows: His firm consists of himself, his brother, and the President of the Jeffersonville Railroad, Indiana. He is from Louisville, left there when Governor Morehead was arrested, went to Nashville, and left just before the city was taken by the Union troops. Went to New Orleans, left there just before the city was taken, went to Liverpool, left there, went to Montreal, and went into business; stayed in Montreal until last December, came here with his brother younger than himself, and set up the brokers’ business. He claims to have had a capital in greenbacks of eighty thousand (80,000) dollars, thirty thousand (30,000) put in by himself, ten thousand (10,000) by his brother, and forty thousand (40,000) by the other partner. This in greenbacks equal now at two forty-five (2-45) to about thirty thousand (30,000) dollars in gold. On this capital he was enabled to buy and pay for, not as balances but actually in currency, almost twelve million (12,000,000) of dollars in gold within the last fortnight, and now is carrying about three millions (3,000,000). This shows that there is something behind him.

“He confessed that he left Louisville afraid of being arrested for his political offenses. During the cross examination he confessed he was agent for the Peoples’ Bank of Kentucky, a secession concern which is doubtless an agent for Jeff Davis. Having no territorial jurisdiction, all I could do was to set before him the enormity of his crime, the danger he stood of having forfeited his life by rebellion to the Government, and to say to him that I should be sorry if gold went up any today because as he was so large an operator I should have cause to believe that he was operating for some political purpose, but that this was a free country and I had no right to control him. Does the Secretary of War suppose that if I had an actual and not an emasculated command in the City of New York, such a rascal would have left my office without my knowing where to find him? He said, indeed, when he went out, that he thought he should not buy gold any more, and sell today all he has. It has got noised around a little that we are looking after the gold speculators, and gold has not risen any today up to five (5) o’clock, the time which I am now writing, although Mr. Belmont’s bet is that it would be at three hundred (300) before election, and the Treasury is not selling.”

On November 9, the day after the election, Secretary Stanton requested that President Lincoln come to the War Department. “They are to consult on some suggestions of Butler’s who wants to grab and incarcerate some gold gamblers. The President doesn’t like to sully victory with any harshness.” Stanton replied to Butler: “Your communication of day before yesterday has been submitted to the President who has directed the Secretary of the Treasury to be conferred with on that part which relates to the gold conspirators. Your views have been explained to the Secretary of the Treasury and when his opinion is received instructions will be sent to you by telegraph.”

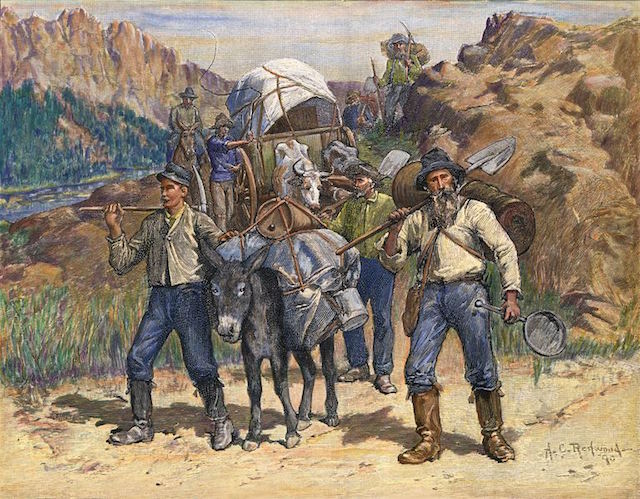

Fortune seekers traveling to the California goldfields to find new diggings during the California Gold Rush era, 1849. Stock Montage/Archive Photos/Getty Images

While the war waged in the East, Californians mined gold in the West. General Ulysses S. Grant observed “I do not know what we would do in this great national emergency were it not for the gold sent from California.” One of the crises that President Lincoln had to handle was the legal fight over ownership of Almaden gold mine in northern California. Lincoln sent his close friend and political ally Leonard Swett to California to resolve the situation. Instead, Swett managed to make the situation worse. On the night he was assassinated, Lincoln said goodbye to House Speaker Schuyler Colfax, who was departing on a trip to California. Lincoln said “Now that the rebellion is overthrown, and we know pretty nearly the amount of our national debt, the more gold and silver we mine makes the payment of that debt so much easier.”

Author and Source UNKNOWN