The Civil War was fought, claimed the Union army surgeon general, “at the end of the medical Middle Ages.” Little was known about what caused disease, how to stop it from spreading, or how to cure it. Surgical techniques ranged from the barbaric to the barely competent.

The Civil War was fought, claimed the Union army surgeon general, “at the end of the medical Middle Ages.” Little was known about what caused disease, how to stop it from spreading, or how to cure it. Surgical techniques ranged from the barbaric to the barely competent.

A Civil War soldier’s chances of not surviving the war was about one in four. These fallen men were cared for by a woefully underqualifled, understaffed, and undersupplied medical corps. Working against incredible odds, however, the medical corps increased in size, improved its techniques, and gained a greater understanding of medicine and disease every year the war was fought.

During the period just before the Civil War, a physician received minimal training. Nearly all the older doctors served as apprentices in lieu of formal education. Even those who had attended one of the few medical schools were poorly trained.

In Europe, four-year medical schools were common, laboratory training was widespread, and a greater understanding of disease and infection existed. The average medical student in the United States, on the other hand, trained for two years or less, received practically no clinical experience, and was given virtually no laboratory instruction. Harvard University, for instance, did not own a single stethoscope or microscope until after the war.

When the war began, the Federal army had a total of about 98 medical officers, the Confederacy just 24. By 1865, some 13,000 Union doctors had served in the field and in the hospitals; in the Confederacy, about 4,000 medical officers and an unknown number of volunteers treated war casualties.

In both the North and South, these men were assisted by thousands of women who donated their time and energy to help the wounded. It is estimated that more than 4,000 women served as nurses in Union hospitals; Confederate women contributed much to the effort as well.

Although Civil War doctors were commonly referred to as “butchers” by their patients and the press, they managed to treat more than 10 million cases of injury and illness in just 48 months and most did it with as much compassion and competency as possible. Poet Walt Whitman, who served as a volunteer in Union army hospitals, had great respect for the hardworking physicians, claiming that “All but a few are excellent men…

Approximately 620,000 men-360,000 Northerners and 260,000 Southerners-died in the four-year conflict, a figure that tops the total fatalities of all other wars in which America has fought. Of these numbers, approximately 110,000 Union and 94,000 Confederate men died of wounds received in battle.

Every effort was made to treat wounded men within 48 hours; most primary care was administered at field hospitals located far behind the front lines. Those who survived were then transported by unreliable and overcrowded ambulances-two-wheeled carts or four-wheeled wagons-to army hospitals located in nearby cities and towns.

The most common Civil War small arms ammunition was the dreadful minnie ball, which tore an enormous wound on impact: it was so heavy that an abdominal or head wound was almost always fatal, and a hit to an extremity usually shattered any bone encountered. In addition, bullets carried dirt and germs into the wound that often caused infection.

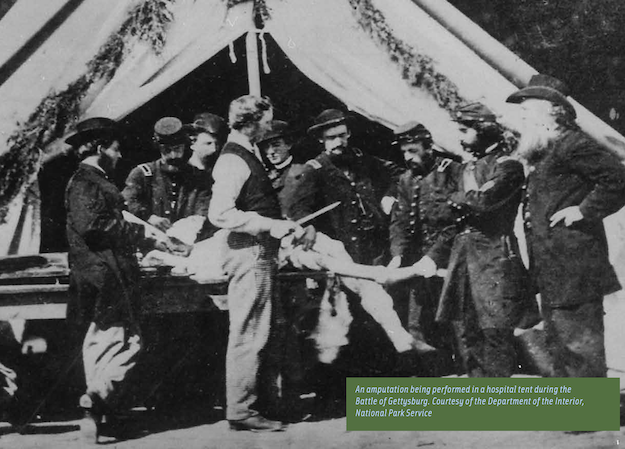

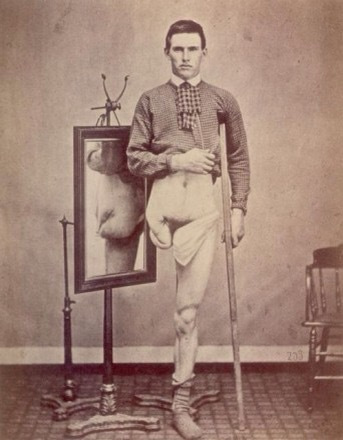

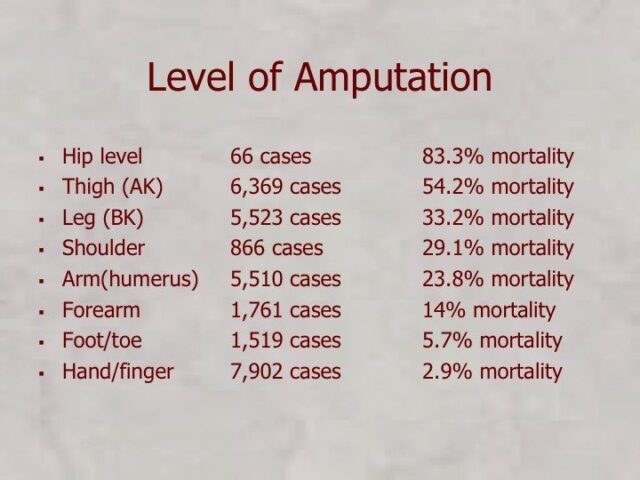

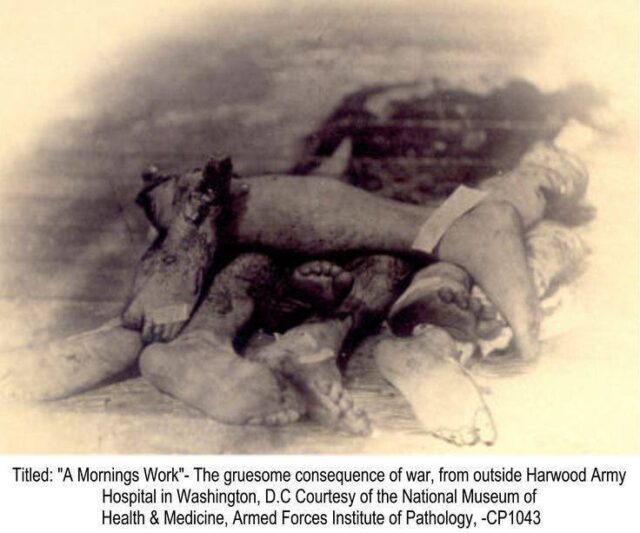

Of the approximately 175,000 wounds to the extremities received among Federal troops, about 30,000 led to amputation; roughly the same proportion occurred in the Confederacy. One witness described a common surgeon’s tent this way:

“Tables about breast high had been erected upon which the screaming victims were having legs and arms cut off. The surgeons and their assistants, stripped to the waist and bespattered with blood, stood around, some holding the poor fellows while others, armed with long, bloody knives and saws, cut and sawed away with frightful rapidity, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile nearby as soon as removed.”

Contrary to popular myth, most amputees did not experience the surgery without anesthetic. Ample doses of chloroform were administered beforehand; the screams heard were usually from soldiers just informed that they would lose a limb or who were witness to the plight of other soldiers under the knife.

Those who survived their wounds and surgeries still had another hurdle, however: the high risk of infection. While most surgeons were aware of a relationship between cleanliness and low infection rates, they did not know how to sterilize their equipment.

Due to a frequent shortage of water, surgeons often went days without washing their hands or instruments, thereby passing germs from one patient to another as he treated them. The resulting vicious infections, commonly known as “surgical fevers,” are believed to have been caused largely by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, bacterial cells which generate pus, destroy tissue, and release deadly toxins into the bloodstream.

Gangrene, the rotting away of flesh caused by the obstruction of blood flow, was also common after surgery. Despite these fearful odds, nearly 75 percent of the amputees survived.

While the average soldier believed the bullet was his most nefarious foe, disease was the biggest killer of the war. Of the Federal dead, roughly three out of five died of disease, and of the Confederate, perhaps two out of three.

One of the reasons for the high rates of disease was the slipshod recruiting process that allowed under- or over-age men and those in noticeably poor health to join the armies on both sides, especially in the first year of the war.

In fact, by late 1862, some 200,000 recruits originally accepted for service were judged physically unfit and discharged, either because they had fallen ill or because a routine examination revealed their frail condition.

About half of the deaths from disease during the Civil War were caused by intestinal disorders, mainly typhoid fever, diarrhea, and dysentery. The remainder died from pneumonia and tuberculosis. Camps populated by young soldiers who had never before been exposed to a large variety of common contagious diseases were plagued by outbreaks of measles, chickenpox, mumps, and whooping cough.

The culprit in most cases of wartime illness, however, was the shocking filth of the army camp itself. An inspector in late 1861 found most Federal camps ‘littered with refuse, food, and other rubbish, sometimes in an offensive state of decomposition; slops deposited in pits within the camp limits or thrown out of broadcast; heaps of manure and offal close to the camp.”

As a result, bacteria and viruses spread through the camp like wildfire. Bowel disorders constituted the soldiers’ most common complaint. The Union army reported that more than 995 out of every 1,000 men eventually contracted chronic diarrhea or dysentery during the war; the Confederates fared no better.

Typhoid fever was even more devastating. Perhaps one-quarter of noncombat deaths in the Confederacy resulted from this disease, caused by the consumption of food or water contaminated by salmonella bacteria.

Epidemics of malaria spread through camps located next to stagnant swamps teeming with anopheles mosquito. Although treatment with quinine reduced fatalities, malaria nevertheless struck approximately one quarter of all servicemen; the Union army alone reported one million cases of it during the course of the war.

Poor diet and exposure to the elements only added to the burden. A simple cold often developed into pneumonia, which was the third leading killer disease of the war, after typhoid and dysentery.

Throughout the war, both the South and the North struggled to improve the level of medical care given to their men. In many ways, their efforts assisted in the birth of modern medicine in the United States.

More complete records on medical and surgical activities were kept during the war than ever before, doctors became more adept at surgery and at the use of anesthesia, and perhaps most importantly, a greater understanding of the relationship between cleanliness, diet, and disease was gained not only by the medical establishment but by the public at large.

Another important advance took place in the field of nursing, where respect for the role of women in medicine rose considerably among both doctors and patients.

Chapter II: Medical Education & Training during the Civil War

The Civil War provided intensive, on-the-job training for thousands of physicians and other caregivers. Many doctors performed surgical procedures for the first time during the war.

They also devised new approaches to diseases and conditions and developed follow-up treatment for patients, including the recording of detailed medical histories. Their wartime experiences paved the way for later developments in medical education.

In the mid-1800s, European cities, especially Paris, Berlin and Vienna, were centers for medical education, and a number of Americans studied medicine abroad. By 1860, there were 40 medical schools in the United States.

In the mid-1800s, European cities, especially Paris, Berlin and Vienna, were centers for medical education, and a number of Americans studied medicine abroad. By 1860, there were 40 medical schools in the United States.

The four institutions in Pennsylvania were all located in Philadelphia, including the country’s first medical school, the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania. At these four Philadelphia schools, there were 30 faculty members for a total of about 1,200 students.

Medical school curricula and requirements varied, but the course of study was shorter than it is today. Students took courses for a year, then repeated the same courses the following year.

Except for practical anatomy, the teaching was entirely by lecture, with a strong emphasis on the memorization of facts. Textbooks were central to medical education, as there was very little clinical or laboratory coursework.

However, students also studied collections of specimens, such as the many organs and bones preserved in the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. They frequently supplemented their training with private courses, especially in anatomy. Independent anatomy schools, including the Philadelphia School of Anatomy founded by Dr. W. W. Keen, provided demonstrations, lectures and hands-on dissecting practice.

After finishing their coursework, most medical students gained practical medical experience by working as anatomy demonstrators or preceptors for a year or two, or by serving as apprentices with established doctors or in hospitals. There were no standardized medical exams and no regulations of the profession.

To become Union military surgeons, however, doctors had to pass extensive written and oral examinations. Some were even required to examine patients and to operate on cadavers to demonstrate their surgical skills.

Medical science of the era consisted of gross anatomy (the body’s basic structures), physiology (the body’s functions), pathology (the effects of disease on the body), and materia medica (substances used for healing, now called pharmacology).

Several alternative systems of medicine also flourished during the 1800s, including homeopathy, which uses diluted substances to treat diseases. The country’s first homeopathic medical school was founded in Philadelphia in 1848. Eclectic medicine, which combined botanical remedies with physical therapy, was also popular for a time.

There were large gaps in medical knowledge in the mid-1800s. Doctors did not know that germs (microscopic organisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa) caused many diseases.

Most physicians believed that diseases were spread by poisonous air, called miasma after the Greek word for pollution. Therefore, they did not follow antiseptic practices such as disinfecting wounds and cleaning instruments.

At the same time, however, medicine was becoming increasingly scientific. Physicians began to rely on observed evidence rather than ancient theories. Microscopy was frequently used for the examination and study of pathological tissues, leading to greater understanding of the effects of disease on the body.

At the same time, however, medicine was becoming increasingly scientific. Physicians began to rely on observed evidence rather than ancient theories. Microscopy was frequently used for the examination and study of pathological tissues, leading to greater understanding of the effects of disease on the body.

Later in the century, medicine began to become a modern profession, with examinations, licensing, codes of ethics and increasing specialization. Professional organizations such as the College of Physicians of Philadelphia contributed to these developments.

Chapter III: Medical practices during the War of Northern Aggression

** Below, in the Confederate section, there is considerable detail regarding amputations. The estimate accounts for both the South and North . . . 30,000 amputations were done.

~ Medicine in the American Civil War ~

~ Medicine in the American Civil War ~

The state of medical knowledge at the time of the Civil War was extremely primitive. Doctors did not understand infection, and did little to prevent it. It was a time before antiseptics, and a time when there was no attempt to maintain sterility during surgery. No antibiotics were available, and minor wounds could easily become infected, and hence fatal. While the typical soldier was at very high risk of being shot and killed in combat, he faced an even greater risk of dying from disease.

~ Background ~

Before the Civil War, the armies tended to be small, largely because of the logistics of supply and training. Musket fire, well known for its inaccuracy, kept casualty rates lower than they might have been. The advent of railroads, industrial production, and canned food allowed for much larger armies, and the Minié ball rifle brought about much higher casualty rates. The work of Florence Nightingale in the Crimean War brought the deplorable situation of military hospitals to the public attention, although reforms were often slow in coming.

~ Union ~

The hygiene of the camps was poor, especially at the beginning of the war when men who had seldom been far from home were brought together for training with thousands of strangers. First came epidemics of the childhood diseases of chicken pox, mumps, whooping cough, and, especially, measles.

Operations in the South meant a dangerous and new disease environment, bringing diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malaria. There were no antibiotics, so the surgeons prescribed coffee, whiskey, and quinine. Harsh weather, bad water, inadequate shelter in winter quarters, poor policing of camps and dirty camp hospitals took their toll. This was a common scenario in wars from time immemorial, and conditions faced by the Confederate army were even worse.

When the war began, there were no plans in place to treat wounded or sick Union soldiers. After the Battle of Bull Run, the United States government took possession of several private hospitals in Washington, D.C., Alexandria, Virginia, and surrounding towns.

Union commanders believed the war would be short and there would be no need to create a long-standing source of care for the army’s medical needs. This view changed after the appointment of General George B. McClellan and the organization of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan appointed the first medical director of the army, surgeon Charles S. Tripler, on August 12, 1861.

Tripler created plans to enlist regimental surgeons to travel with armies in the field, and the creation of general hospitals for the badly wounded to be taken to for recovery and further treatment. To implement the plan, orders were issued on May 25 that each regiment must recruit one surgeon and one assistant surgeon to serve before they could be deployed for duty. These men served in the initial makeshift regimental hospitals.

Tripler created plans to enlist regimental surgeons to travel with armies in the field, and the creation of general hospitals for the badly wounded to be taken to for recovery and further treatment. To implement the plan, orders were issued on May 25 that each regiment must recruit one surgeon and one assistant surgeon to serve before they could be deployed for duty. These men served in the initial makeshift regimental hospitals.

In 1862 William A. Hammond became surgeon general and launched a series of reforms. He founded the Army Medical Museum, and had plans for a hospital and a medical school in Washington; a central laboratory for chemical and pharmaceutical preparations was created; much more extensive recording was required from the hospitals and the surgeons. Hammond raised the requirements for admission into the Army Medical Corps.

The number of hospitals was greatly increased and he paid close attention to aeration. New surgeons were promoted to serving at the brigade level with the rank of Major. The Surgeon Majors were assigned staffs and were charged with overseeing a new brigade level hospital that could serve as an intermediary level between the regimental and general hospitals. Surgeon Majors were also charged with ensuring that regimental surgeons were in compliance with the orders issued by the Medical Director of the Army.

In the Union skilled, well-funded medical organizers took proactive action, especially in the much enlarged United States Army Medical Department, and the United States Sanitary Commission, a new private agency.

Numerous other new agencies also targeted the medical and morale needs of soldiers, including the United States Christian Commission as well as smaller private agencies such as the Women’s Central Association of Relief for Sick and Wounded in the Army (WCAR) founded in 1861 by Henry Whitney Bellows, and Dorothea Dix.

Systematic funding appeals raised public consciousness, as well as millions of dollars. Many thousands of volunteers worked in the hospitals and rest homes, most famously poet Walt Whitman. Frederick Law Olmsted, a famous landscape architect, was the highly efficient executive director of the Sanitary Commission.

Systematic funding appeals raised public consciousness, as well as millions of dollars. Many thousands of volunteers worked in the hospitals and rest homes, most famously poet Walt Whitman. Frederick Law Olmsted, a famous landscape architect, was the highly efficient executive director of the Sanitary Commission.

States could use their own tax money to support their troops as Ohio did. Following the unexpected carnage at the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, the Ohio state government sent 3 steamboats to the scene as floating hospitals with doctors, nurses and medical supplies. The state fleet expanded to eleven hospital ships. The state also set up 12 local offices in main transportation nodes to help Ohio soldiers moving back and forth.

Field hospitals were initially in the open air, with tent hospitals that could hold only six patients first being used in 1862; after many major battles the injured had to receive their care in the open. As the war progressed, nurses were enlisted, generally two per regiment. In the general hospitals one nurse was employed for about every ten patients.

The first permanent general hospitals were ordered constructed during December 1861 in the major hubs of military activity in the eastern and western United States. An elaborate system of ferrying wounded and sick soldiers from the brigade hospitals to the general hospitals was set up. At first the system proved to be insufficient and many soldiers were dying in mobile hospitals at the front and could not be transported to the general hospitals for needed care.

The first permanent general hospitals were ordered constructed during December 1861 in the major hubs of military activity in the eastern and western United States. An elaborate system of ferrying wounded and sick soldiers from the brigade hospitals to the general hospitals was set up. At first the system proved to be insufficient and many soldiers were dying in mobile hospitals at the front and could not be transported to the general hospitals for needed care.

The situation became apparent to military leaders in the Peninsular Campaign in June 1862 when several thousand soldiers died for lack of medical treatment. Dr. Jonathan Letterman was appointed to succeed Tripler as the second Medical Director of the Army in 1862 and completed the process of putting together a new ambulance corps. Each regiment was assigned two wagons, one carrying medical supplies, and a second to serve as a transport for wounded soldiers.

The ambulance corps was placed under the command of Surgeon Majors of the various brigades. In August 1863 the number of transport wagons was increased to three per regiment.

Union medical care improved dramatically during 1862. By the end of the year each regiment was being regularly supplied with a standard set of medical supplies included medical books, supplies of medicine, small hospital furniture like bed-pans, containers for mixing medicines, spoons, vials, bedding, lanterns, and numerous other implements.

A new layer of medical treatment was added in January 1863. A division level hospital was established under the command of a Surgeon-in-Chief. The new divisional hospitals took over the role of the brigade hospitals as a rendezvous point for transports to the general hospitals.

The wagons transported the wounded to nearby railroad depots where they could be quickly transported to the general hospitals at the military supply hubs. The divisional hospitals were given large staffs, nurses, cooks, several doctors, and large tents to accommodate up to one hundred soldiers each. The new division hospitals began keeping detailed medical records of patients. The divisional hospitals were established at a safe distance from battlefields where patients could be safely helped after transport from the regimental or brigade hospitals.

The wagons transported the wounded to nearby railroad depots where they could be quickly transported to the general hospitals at the military supply hubs. The divisional hospitals were given large staffs, nurses, cooks, several doctors, and large tents to accommodate up to one hundred soldiers each. The new division hospitals began keeping detailed medical records of patients. The divisional hospitals were established at a safe distance from battlefields where patients could be safely helped after transport from the regimental or brigade hospitals.

Although the divisional hospitals were placed in safe locations, because of their size they could not be quickly packed in the event of a retreat. Several divisional hospitals were lost to Confederates during the war, but in almost all occasions their patients and doctors were immediately paroled if they would swear to no longer bear arms in the conflict. On a few occasions, the hospitals and patients were held several days and exchanged for Confederate prisoners of war.

The both Armies learned many lessons and in 1886, it established the Hospital Corps. The Sanitary Commission collected enormous amounts of statistical data, and opened up the problems of storing information for fast access and mechanically searching for data patterns.

~ Confederacy ~

The Confederacy was quicker to authorize the establishment of a medical corps than the Union, but the Confederate medical corp was at a considerable disadvantage throughout the war primarily due to the lesser resources of the Confederate government. A Medical Department was created with the initial army structure by the provisional Confederate government on February 26, 1861.

President Jefferson Davis appointed David C. DeLeon Surgeon General. Although a leadership for a medical corp was created, an error by the copyist in the creation of the military regulations of the Confederacy omitted the section for medical officers, and none were mustered into their initial regiments. Many physicians enlisted in the army as privates, and when the error was discovered in April, many of the physicians were pressed into serving as regimental surgeons.

DeLeon had little experience with military medicine, and he and his staff of twenty-five began creating plans to implement army-wide medical standards. The Confederate government appropriated money to purchase hospitals to serve the army, and the development of field services began after the First Battle of Manassas.

DeLeon had little experience with military medicine, and he and his staff of twenty-five began creating plans to implement army-wide medical standards. The Confederate government appropriated money to purchase hospitals to serve the army, and the development of field services began after the First Battle of Manassas.

The early hospitals were quickly overrun by wounded, and hundreds had to be sent by train to other southern cities for care following the battle. As a result of the poor planning, Davis demoted DeLeon and replaced him with Samuel Preston Moore. Moore had more experience than DeLeon and quickly moved to speed the implementation of medical standards. Because many of the surgeons in the regiments had been pressed into service, some were not qualified to be surgeons. Moore began reviewing the surgeons and replacing those found to be inadequate for their duties.

Initially the Confederacy employed a policy of furloughing wounded soldiers to return home for recovery. This was a result of their lack of field hospitals and limited capacity in their general hospitals. In August 1861, the army began the construction of new larger hospitals in several southern cities and the furloughing policy was gradually halted.

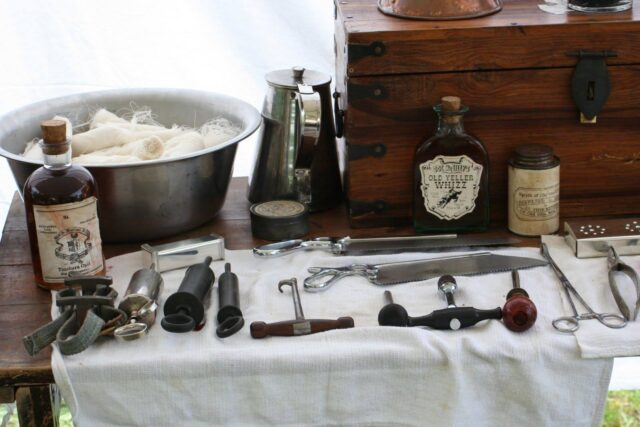

The earliest recruits for surgeons were required to bring their own supplies, a practice that was ended during 1862. The government began providing each regiment with a pack with medical supplies including medicines and surgical instruments. The Confederacy, however, had limited access to medicinal supplies and relied on their blockade-running ships to import needed medicines from Europe, supplies captured from the North or traded with the North through Memphis.

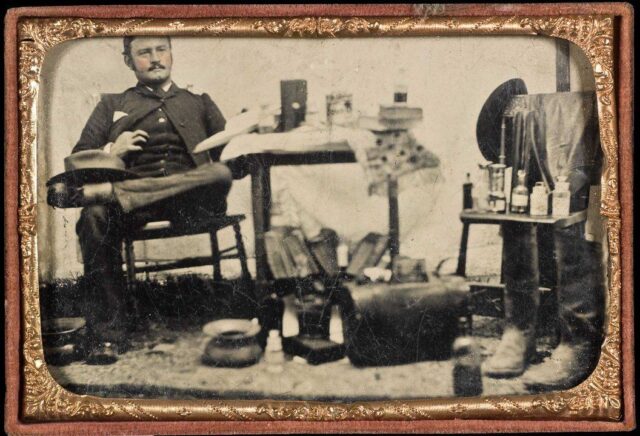

Anesthetics were not in as short supply as medical instruments, something highly prized. Field hospitals were set up at the regimental level and located in an open area behind the lines of battle and staffed by two surgeons, one being senior. It was the responsibility of the regimental surgeons to determine which soldiers could return to duty and which should be sent to the general hospitals.

There were no intermediary hospitals, and each regiment was responsible for transporting its wounded to the nearest rail depot, where the injured were transported to the general hospitals for longer term care. In some of the lengthier battles, buildings were seized to serve as a temporary secondary hospital at a divisional level where the severely wounded could be held. The secondary facilities were staffed by the regimental surgeons, who pooled their resources to care for the wounded and were oversaw by a divisional surgeon.

~ Ambulance system ~

Before the formation of any organized ambulance system, a significant amount of Union and Confederate soldiers lost their lives on the battlefield in wait for medical aid. Even if an army were able to overcome the shortage of ambulances, it was really the lack of organization that made it difficult to recover the wounded on the battlefield. In some cases, those who manned the ambulances were corrupt and sought to steal from the ambulance wagon and the wounded passengers while in some situations they even refused to gather hurt soldiers.

With an insufficient number of ambulances performing assigned tasks, the wounded looked to their comrades to carry them to safety and in essence this removed many soldiers from the battlefield. Due to the overall lightness of the ambulance the ride was very uncomfortable for wounded soldiers, with the terrain being torn up by shells and explosions the ambulance at times would overturn further harming its passengers. It was obvious that the ambulance system needed work for both the Union and the Confederate armies, yet only the Union would fully prosper in this area with the help of Dr. Jonathan Letterman and the beginning stages of the ambulance corps.

Letterman’s revolutionary ideas dramatically improved both the ambulance and the ambulance system. With new designs the common Union ambulance was now composed of a 750 lb wagon that was powered by 2-4 horses and was made to carry 2-6 wounded soldiers. Other accessories that were standard for the improved ambulances included compartments to store medical supplies, stretchers, water, and even removable benches and seats to adapt to the number of passengers.

Letterman’s ideas improved the ambulance system dramatically by setting standards to train the ambulance crew, by having routine ambulance inspections, and also by developing strategical evacuation plans to most efficiently save and transport fallen soldiers. Letterman’s system was so efficient that all wounded soldiers at The Battle of Antietam were removed from the battlefield and sent to care within one day so this new system saved thousands of Union lives.

Soon after The Battle of Antietam began the formation of the ambulance corps and while the Confederates were also working out a similar system their constant shortage of ambulances was not adequate enough to summon such an effective force as even some their ambulances came by capturing Union ambulances.

~ Surgery and health outcomes ~

The most common battlefield injury was being wounded by enemy fire. Unless the wounds were minor, this often led to amputation of limbs to prevent infection from setting in, as antibiotics had not yet been discovered. Amputations had to be made at the point above where the wound occurred, often leaving men with stub limbs.

A flap of skin was saved, and stitched to the stump to cover the wound. There were two types of amputations, primary and secondary. The primary amputation was done between 24-48 hours after the injury. The secondary amputation was done after a longer period of time, often because of infection. During this time, there were two main methods of amputation, the flap method and circular method.

The flap method was typically used when an amputation had to be done quickly. The bone was cut above flaps of skin and muscle, which were pulled together to close the wound. The circular method was a circular cut that only allowed a flap of surface skin to cover the wound. The flap method was more likely than the circular method to lead to gangrene, as the deep muscle tissue suffered from lack of circulation.

Approximately 30,000 amputations were performed during the Civil War. Men were generally partially sedated with ether, chloroform or alcohol before surgeries. The use of ether as general anesthesia started in 1846 and the use of chloroform in 1847.

Approximately 30,000 amputations were performed during the Civil War. Men were generally partially sedated with ether, chloroform or alcohol before surgeries. The use of ether as general anesthesia started in 1846 and the use of chloroform in 1847.

Men were generally partially sedated with chloroform or alcohol before surgeries. When properly done, the patient would feel no pain during their surgery, but would not be totally unconscious. Stonewall Jackson, for example, recalled the sound of the saw cutting through the bone of his arm, but recalled no pain. Infection was the most common cause of death of injured soldiers.

Infection occurred for a variety of reasons. Surgeons would typically go from surgery to surgery without cleaning their equipment or their hands; surgeons would use sponges that they only rinsed in water on multiple patients. These practices caused bacteria to spread from patient to patient, from all surgical surfaces, and from the environment, which caused infections in many.

It has been said that the American Civil War was the first “modern war” in terms of technology and lethality of weapons, but that it was simultaneously fought “at the end of the medical Middle Ages.”[citation needed] Very little was known about the causes of disease, and so a minor wound could easily become infected and take a life.

Battlefield surgeons were underqualified and hospitals were generally poorly supplied and staffed. In fact, there were so many wounded and not enough doctors, so doctors were forced to spend only a little time with each patient. They became proficient at quick care. Some surgeons spent as little as 10 minutes on amputating a limb.

The most common battlefield operation was amputation. If a soldier was badly wounded in the arm or leg, amputation was usually the only solution.[citation needed] About 75% of amputees survived the operation.[citation needed] Contrary to popular belief, few soldiers experienced amputation without any anesthetic. Heavy doses of chloroform were administered; in fact, a few soldiers died of chloroform poisoning, rather than their wounds.

The most common battlefield operation was amputation. If a soldier was badly wounded in the arm or leg, amputation was usually the only solution.[citation needed] About 75% of amputees survived the operation.[citation needed] Contrary to popular belief, few soldiers experienced amputation without any anesthetic. Heavy doses of chloroform were administered; in fact, a few soldiers died of chloroform poisoning, rather than their wounds.

A 2016 research paper found that Civil War surgery was effective at improving patient health outcomes. The study finds that “in many cases [surgery] amounted to a doubling of the odds of survival”.

If a wound produced pus, it was thought that it meant the wound was healing, when in fact it meant the injury was infected. Specifically, if the pus was white and thick, the doctors thought it was a good sign. Roughly three in five Union casualties and two in three Confederate casualties died of disease.

~ Women ~

North and South, over 20,000 women volunteered to work in hospitals, usually in nursing care. They assisted surgeons during procedures, gave medicines, supervised the feedings and cleaned the bedding and clothes. They gave good cheer, wrote letters the men dictated, and comforted the dying.

Thomas Nast, “Our Heroines, United States Sanitary Commission,” in Harper’s Weekly, April 9, 1864, via Cushing/Whitney Medical Library at Yale University.

NOTE: The Civil War ultimately opened a variety of arenas for Union and Confederate women’s participation. In the North, the United States Sanitary Commission in particular centralized women’s opportunities to volunteer as nurses, donate supplies, and to raise funds at Sanitary Fairs. This 1864 image from popular periodical Harper’s Weekly celebrates women’s contributions on the battlefield, in the hospital, in the parlor, and at the fair.

The Sanitary Commission handled most of the nursing care of the Union armies, together with necessary acquisition and transportation of medical supplies. Dorothea Dix, serving as the Commission’s Superintendent, was able to convince the medical corps of the value of women working in 350 Commission or Army hospitals.

A representative nurse was Helen L. Gilson (1835–68) of Chelsea, Massachusetts, who served in Sanitary Commission. She supervised supplies, dressed wounds, and cooked special foods for patients on a limited diet.

She worked in hospitals after the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. She was a successful administrator, especially at the hospital for black soldiers at City Point, Virginia.

The middle class women North and South who volunteered provided vitally needed nursing services and were rewarded with a sense of patriotism and civic duty in addition to opportunity to demonstrate their skills and gain new ones, while receiving wages and sharing the hardships of the men.

Mary Livermore, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles. After the war some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, Sarah Palmer Young, and Sarah Emma Edmonds.

Several thousand women were just as active in nursing in the Confederacy, but were less well organized and faced severe shortages of supplies and a much weaker system of 150 hospitals. Nursing and vital support services were provided not only by matrons and nurses, but also by local volunteers, slaves, free blacks, and prisoners of war.

Clara Barton

~ Aftermath ~

Based on their experiences in the war, many veterans went on to develop high standards for medical care and new medicines. The modern pharmaceutical industry began developing in the decades after the war. Colonel Eli Lilly had been a pharmacist; he built a pharmaceutical empire after the war. Clara Barton founded the American Red Cross to provide civilian nursing services in wartime.