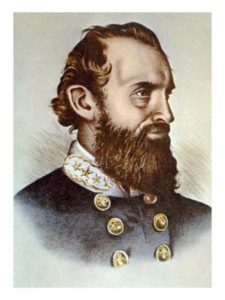

Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson

Lieutenant-General Thomas Jonathan Jackson was one of those rare historical characters who is claimed by all people–a man of his race, almost as much as of the Confederacy. No war has produced a military celebrity more remarkable, nor one whose fame will be more enduring. He was born January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Va., and his parents, who were of patriotic Revolutionary stock, dying while he was but a child, he was reared and educated by his kindred in the pure and simple habits of rural life, taught in good English schools, and is described as a “diligent, plodding scholar, having a strong mind, though it was slow in development.” But he was in boyhood a leader among his fellow-students in the athletic sports of the times, in which he generally managed his side of the contest so as to win the victory. By this country training he became a bold and expert rider and cultivated that spirit of daring which being held sometimes in abeyance displayed itself in his Mexican service, and then suddenly again in the Confederate war.

In June, 1842, at the age of eighteen, he was appointed to a cadet-ship in the military academy at West Point, where,General Stonewall Jackson commencing with the disadvantages of inadequate preparation, he overcame obstacles by such determination as to rise from year to year in the estimation of the faculty. He graduated June 30, 1846, at the age of twenty-two years, receiving brevet rank as second-lieutenant at the beginning of the Mexican war, and was ordered to report for duty with the First Regular artillery, with which he shared in the many brilliant battles which General Scott fought from Vera Cruz to the City of Mexico. He was often commended for his soldierly conduct and soon received successive promotions for gallantry at Contreras and Churubusco. Captain Magruder, afterwards a Confederate general, thus mentioned him in orders: “If devotion, industry, talent, and gallantry are the highest qualities of a soldier, then is he entitled to the distinction which their possession confers.” Jackson was one of the volunteers in the storming of Chapultepec, and for his daring there was brevetted major, which was his rank at the close of the Mexican war.

His religious character, which history has and will inseparably connect with his military life, appears to have begun forming in the City of Mexico, where his attention was directed to the subject of the variety of beliefs on religious questions. His amiable and affectionate biographer (Mrs. Jackson) mentions that Colonel Francis Taylor, the commander of the First artillery, under whom Jackson was serving, was the first man to speak to him on the subject of personal religion. Jackson had not at any time of his life yielded to the vices, and was in all habits strictly moral, but had given no particular attention to the duties enjoined by the church. Convinced now that this neglect was wrong, he began to study the Bible and pursued his inquiries until he finally united (1851) with the Presbyterian church. His remarkable devoutness of habit and unwavering confidence in the truth of his faith contributed, it is conceded, very greatly to the full development of his singular character, as well as to his marvelous success.

In 1848 Jackson’s command was stationed at Fort Hamilton for two years, then at Fort Meade, in Florida, and from that station he was elected to a chair in the Virginia military institute at Lexington in 1851, which he accepted, and resigning his commission, made Lexington his home ten years, and until he began his remarkable’ career in the Confederate war. Two years later, 1853, he married Miss Eleanor, daughter of Rev. Dr. Junkin, president of Washington college, but she lived scarcely more than a year. Three years after, July 16, 1857, his second marriage occurred, with Miss Mary Anna, daughter of Rev. Dr. H. R- Morrison, of North Carolina, a distinguished educator, whose other daughters married men who attained eminence in civil and military life, among them being General D. H. Hill, General Rufus Barringer, and Chief Justice A. C. Avery.

The only special incident occurring amidst the educational and domestic life of Major Jackson, which flowed on serenely from this hour, was the summons of the cadets of the Institute by Governor Letcher, to proceed to Harper’s Ferry on the occasion of the raid of John Brown in 1859.

During the presidential campaign of 1860 Major Jackson visited New England and there heard enough to arouse his fears for the safety of the Union. At the election of that year he cast his vote for Breckinridge on the principle that he was a State rights man, and after Lincoln’s election he favored the policy of contending in the Union rather than out of it, for the recovery of the ground that had thus been lost. The course of coercion, however, alarmed him, and the failure of the Peace congress persuaded him that if the United States persisted in their course war would certainly result. His State saw as he did, and on the passage of its ordinance of secession, the military cadets under the command of Major Jackson were ordered to the field by the governor of Virginia. The order was promptly obeyed April 21, 1861, from which date his Confederate military life began.

During the presidential campaign of 1860 Major Jackson visited New England and there heard enough to arouse his fears for the safety of the Union. At the election of that year he cast his vote for Breckinridge on the principle that he was a State rights man, and after Lincoln’s election he favored the policy of contending in the Union rather than out of it, for the recovery of the ground that had thus been lost. The course of coercion, however, alarmed him, and the failure of the Peace congress persuaded him that if the United States persisted in their course war would certainly result. His State saw as he did, and on the passage of its ordinance of secession, the military cadets under the command of Major Jackson were ordered to the field by the governor of Virginia. The order was promptly obeyed April 21, 1861, from which date his Confederate military life began.

Jackson’s valuable service was given to Virginia in the occupation of Harper’s Ferry and several subsequent small affairs, but his fame became general from the battle of First Manassas. It was at one of the crises of that first trial battle between the Federal and Confederate troops that he was given the war name of “Stonewall,” by which he will be always designated. The true story will be often repeated that on being notified of the Federal advance to break the Confederate line he called out, “We will give them the bayonet,” and a few minutes later the steadiness with which the brigade received the shock of battle caused the Confederate General Bee to exclaim: “There stands Jackson like a stone wall.“

Jackson’s valuable service was given to Virginia in the occupation of Harper’s Ferry and several subsequent small affairs, but his fame became general from the battle of First Manassas. It was at one of the crises of that first trial battle between the Federal and Confederate troops that he was given the war name of “Stonewall,” by which he will be always designated. The true story will be often repeated that on being notified of the Federal advance to break the Confederate line he called out, “We will give them the bayonet,” and a few minutes later the steadiness with which the brigade received the shock of battle caused the Confederate General Bee to exclaim: “There stands Jackson like a stone wall.“

He was commissioned brigadier-general June 17, 1861, and was promoted to major-general October 7, 1861, with the wise assignment to command of the Valley district, which he assumed in November of that year. With a small force he began even in winter a series of bold operations in the great Virginia valley, and opened the spring campaign of 1862, on plans concerted between General Joseph E. Johnston and himself, by attacking the enemy at Kernstown, March 23rd, where he sustained his only repulse; but even in the movement which resulted in a temporary defeat he caused the recall of a considerable Federal force designed to strengthen McClellan in the advance against Richmond. The next important battle was fought at McDowell, in which Jackson won a decided victory over Fremont. Then moving with celerity and sagacity he drove Banks at Front Royal, struck him again at Newtown, and at length utterly routed him. After this, turning about on Shields, he overthrew his command also, and thus, in one month’s campaign, broke up the Federal forces which had been sent to “crush him.” In these rapidly executed operations he had successfully fought five battles against three distinct armies, requiring four hundred miles, marching to compass the fields.

This Valley campaign of 1862 was never excelled, according to the opinions expressed by military men of high rank and long experience in war. It is told by Dr. McGuire, the chief surgeon of Jackson’s command, that with swelling heart he had “heard some of the first soldiers and military students of England declare that within the past two hundred years the English speaking race has produced but five soldiers of the first rank – Marlborough, Washington, Wellington, Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and that this campaign in the valley was superior to either of those made by Napoleon in Italy.” One British officer, who teaches strategy in a great European college, told Surgeon McGuire that he used this campaign as a model of strategy and tactics, dwelling upon it for several months in his lectures; that it was taught in the schools of Germany, and that Von Moltke, the great strategist, declared it was without a rival in the world’s history.

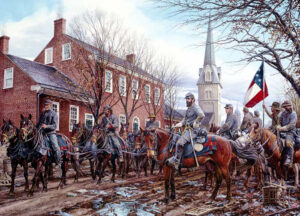

AFTER THE STORM, Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 16, 1862 – artist John Paul Strain

After this brilliant service for the Confederacy Jackson joined Lee at Richmond in time to strike McClellan’s flank at the battle of Cold Harbor, and to contribute to the Federal defeat in the Seven Days’ battles around Richmond. In the campaign against Pope, undertaken by Lee after he had defeated McClellan, Jackson was sent on a movement suited to his genius, capturing Manassas Junction, and foiling Pope until the main battle of Second Manassas, August 30, 1862, under Lee, despoiled that Federal general of all his former honors. The Maryland campaign immediately followed, in which Jackson led in the capture of Harper’s Ferry September 15th, taking 11,500 prisoners, and an immense amount of arms and stores, just preceding the battle of Sharpsburg, in which he also fought with notable efficiency at a critical juncture. The promotion to lieutenant-general was now accorded him, October 10, 1862. At the battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862, Lieutenant-General Jackson held the Confederate right against all Federal assaults. The Federal disaster in this battle resulted in the resignation of Burnside and the reorganization of the army under General Hooker in 1863.

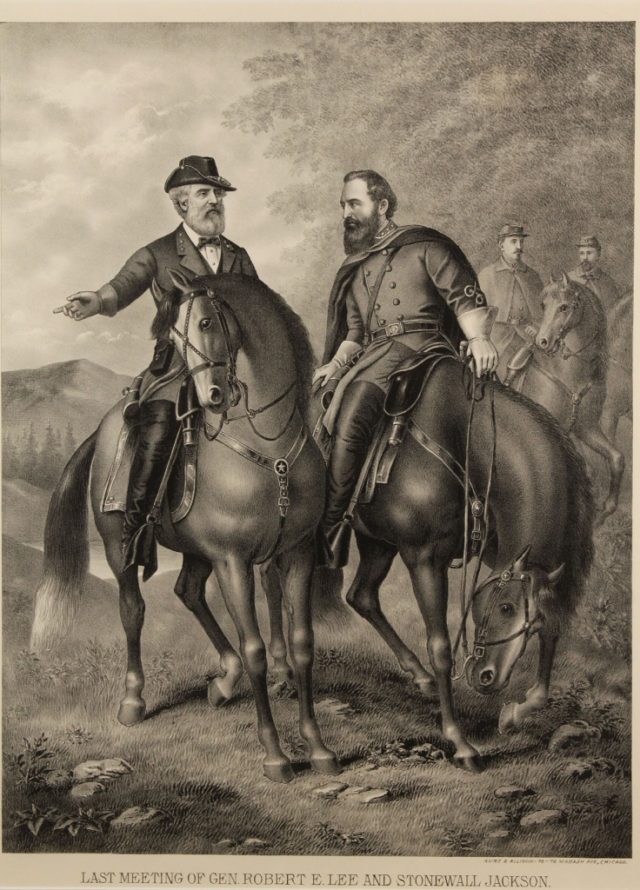

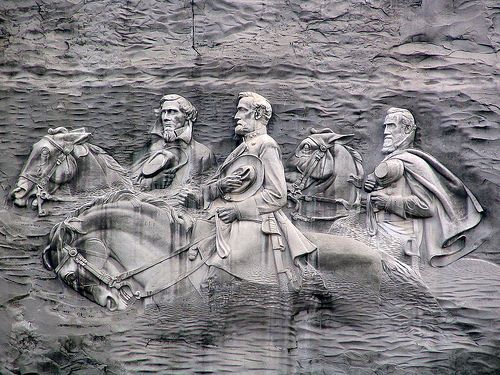

Generals Robert E. Lee and ‘Stonewall’ Jackson at their final meeting.

After the most complete preparations Hooker advanced against Lee at Chancellorsville, who countervailed all the Federal general’s plans by sending Jackson to find and crush his right flank, which movement was in the process of brilliant accomplishment when Jackson,who had passed his own lines to make a personal inspection of the situation, was fired upon and fatally wounded by a line of Confederates who unhappily mistook him and his escort for the enemy. The glory of the achievement which Lee and Jackson planned, fell upon General Stuart next day, who, succeeding Jackson in command, ordered that charge which became so ruinous to Hooker, with the thrilling watchword, “Remember Jackson.”

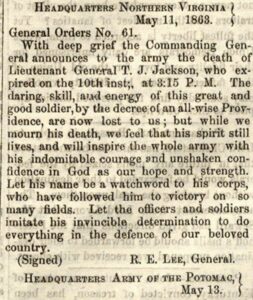

General Jackson lived a few days and died (May 10, 1863) lamented more than any soldier who had fallen. Lee said: “I have lost my right arm.” The army felt that his place could not be easily supplied. The South was weighted with grief. After the war, when the North dispassionately studied the man they ceased to wonder at the admiration in which he was held by the world. He was buried at Lexington, Va., where a monument erected by affection marks his grave. “For centuries men will come to Lexington as a Mecca, and to this grave as a shrine, and wonderingly talk of this man and his mighty deeds. Time will only add to his great fame – his name will be honored and revered forever.”

General Jackson lived a few days and died (May 10, 1863) lamented more than any soldier who had fallen. Lee said: “I have lost my right arm.” The army felt that his place could not be easily supplied. The South was weighted with grief. After the war, when the North dispassionately studied the man they ceased to wonder at the admiration in which he was held by the world. He was buried at Lexington, Va., where a monument erected by affection marks his grave. “For centuries men will come to Lexington as a Mecca, and to this grave as a shrine, and wonderingly talk of this man and his mighty deeds. Time will only add to his great fame – his name will be honored and revered forever.”

Sculpted figures of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson ~ Stone Mountain, Georgia