A recent report shows that 87% of state history standards include no mention of Native American history after 1900.

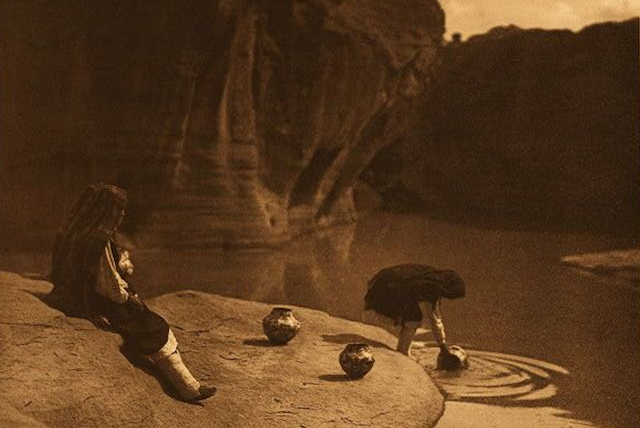

At the old well of Acoma (1904) Tiwa by Edward S. Curtis

On the heels of the National Indian Education Association’s conference held in Minneapolis earlier this fall and just in time for Native American Heritage Month, the nearby Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community announced a $5 million philanthropic campaign to fund resources, curriculum, and training on Native American heritage for teachers and administrators across Minnesota, according to the Star Tribune. “We’re hoping we can move the needle in the narrative in Minnesota and be a model,” Rebecca Crooks-Stratton, the secretary-treasurer for SMSC, told the newspaper.

A recent report by the National Congress of American Indians highlights the need for initiatives like SMSC’s. Summarizing states’ efforts to bring content about indigenous peoples and communities into K-12 classrooms across the country, the report found that 87% of state history standards include no mention of Native American history after 1900, and 27 states don’t mention Native Americans in their K-12 curriculum.

However, 90% of states surveyed reported that they are working to improve the quality of and access to Native American education curriculum, and a majority of states indicated that Native American education is already included in their content standards, although far fewer require it be taught in public schools. Despite a dearth of requirements, educators don’t have to wait for a state mandate to begin integrating Native American studies into their coursework, no matter their subject.

In recent years, there’s been a movement driven by Native American communities, such as the SMSC, as well as individual educators, institutions and states to increase the inclusion of indigenous cultures in education.

Washington has been something of a leader for years. In 2015 it became the second state, behind Montana, to mandate tribal history be taught in the state’s 295 school districts. Unique to Washington, though, is the requirement that schools get input from the state’s 29 federally recognized tribes in the process.

Michael Vendiola, the education director for the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and former program supervisor for the Washington’s Office of Native Education, sees the 2015 mandate as a significant point in the movement toward equity in Native American education.

“For Native people, it’s a matter of having their story told and being accurate and having a local perspective,” Vendiola says. Further, “it severely impacts the success of tribal students in the public school system because most of the time (what is taught comes from) a very narrow point of view — totem poles from Alaska or a bit of Navajo ceremonies. There are over 500 tribes in the U.S. which are clearly more diverse than that.”

Without adequate and nuanced Native American education, it’s a slippery slope into the mascot-related issues that stem from flattened, stereotypical representations of indigenous people. According to Vendiola, these reductions also lead to notions that Native Americans don’t exist in contemporary culture.

The mandate isn’t free of challenges, particularly because it’s unfunded. While it’s required that school districts work with their closest federally recognized tribe to develop the material, “on paper that looks really good but depending on the tribe’s resources … they don’t have curriculum writers,” Vendiola says. “At best they might have a museum or archives that have some records.”

Yet there are other ways that educators can access in-depth information on Native American cultures to include it in the classroom.

Last year the Smithsonian developed Native Knowledge 360 Degrees (NK360°), a national education initiative, and released three new lesson plans in September. Building off a decade of work, NK360° offers free lesson plans for teachers to use.

Jennifer Bumgarner, a seventh-grade English and Language Arts teacher in North Carolina, opted to use NK360° in her classroom. “I have a passion for Native American literature and culture. By choice, I incorporate a lot of Native American studies into my instruction both for cultural and thematic value,” she says.

Bumgarner focuses specifically on the role and responsibilities of Native American individuals to their communities and the role and responsibilities of the community to its individuals. She compares that to what her students are learning about literature. “There are individual parts that make up the whole of literature,” she says.

She says her students have loved the material and she has been sharing it with other teachers in her school, though she isn’t sure if anyone else has begun to use it. She thinks a mandate could work in North Carolina “if it were presented in a way that really showed (educators) the great materials that were available and if it incorporated some of our North Carolina indigenous people who came and spoke about the importance of a new perspective.”

Written by Cinnamon Janzer for US News ~ November 29, 2019