In the South, the term “swallowing the dog” meant pledging allegiance to the United States

What is the meant by the phrase “swallowing the dog”?

What is the meant by the phrase “swallowing the dog”?

For Confederate veterans, the term “swallowing the dog” meant being forced to repeatedly pledge allegiance to the United States whose military forces were occupying the Confederacy.

“Swallowing the dog” is the same feeling of alienation and disgust that Southerners experience today at the sight of President Barack Hussein Obama and Eric “My People” Holder:

“It was the most despised word in the South.” A few took it “as if it was nothing more than a Glass of Lemonade.” Others refused as if it were arsenic. It forced people to reexamine their priorities: principles or bread? They reconsidered what it meant to give their word of honor. For loyal Confederates, it was likened to “swallowing the dog.”

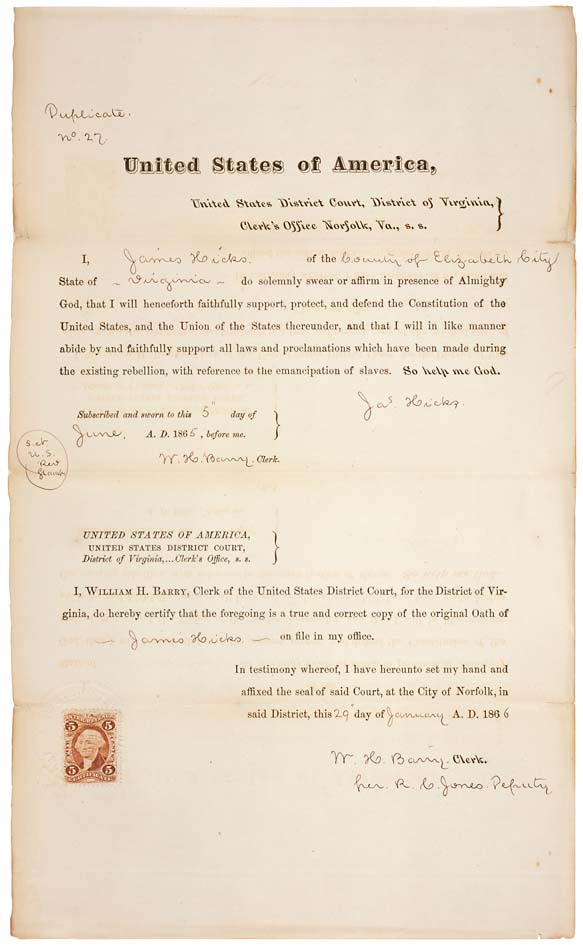

The Oath of Allegiance to the United States became a staple of the Confederate diet. In exchange for the privilege to vote, to transact business, to acquire rations, to perform marriage ceremonies, or even get married. Rebels were forced to gulp down their pride and utter these words: “I do solemnly swear that I hereby renounce all countenance, support and allegiance to the so-called Confederate States of America.”

For a people left crushed a crippled, the requirement of the oath was like pouring salt into an open wound. “I think the exaction of this oath cannot be justified on any grounds whatever whether as of admonition and warning for the future or as punishment for the past,” wrote Henry William Ravenel from South Carolina. “It is simply an arbitrary and tyrannical exercise of power.”

The Western Democrat in Charlotte summed up the situation for most ex-Confederates. “Those who expect to follow any occupation in the country have no alternative but to take the oath.” …

No matter how many times they swallowed the dog, the taste was always foul, and compelling Southerners to swear allegiance over and over required great ingenuity. There was seemingly no end to the inducements Federals contrived to coerce the oath taking. In Columbus, Georgia, ladies were initially required to take the oath in order to receive their mail. Elsewhere in Georgia, letters were opened, in order to test the sincerity of Rebels who had taken the oath. …

In the minds of Southerners, it was doubly insulting to exchange the oath for food. “It was most heart-rending,” observed Cornelia Spencer, “to see daily crowds of country people, from three score and ten down to the unconscious infant carried in its mother’s arms, coming into town to beg for food and shelter, to ask alms from those who had despoiled them.” One poorly educated woman in this circumstance went to the local provost and inquired if she could draw rations. The officer asked if she would take the oath. “Thank you, sir,” said the lady, “there is my cart – please put it in that.” …

Southerners were forced to swear the oath for spiritual food, as well. Even their God had been supplanted by a cold and distant Northern deity, at whose alter they resentfully laid sacrifices. At Richmond, ministers could not perform wedding ceremonies unless they had taken the oath. And couples could not marry without first swearing allegiance.

Given the situation, working in the ranks of the clergy became a high risk occupation. Reading of events unfolding in Missouri, Washingtonian William Owner was outraged that five Catholic priests were arrested and thrown into a cell “with burglars and a nigger ravisher.” Again, their only crime was refusing to swear the oath. …

Like their Catholic counterparts, when Protestant preachers in Missouri failed to pray for Lincoln, they were arrested and their churches were closed …

In various denominations, the hierarchy took it upon itself to discipline those clergymen in its ranks who had chosen the wrong side. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church met in Pittsburgh and passed a series of resolutions “practically upending all … ministers until they had repented of the sin of rebellion.”

“As those in the South, almost to a man were strong supporters of the Confederacy,” explained a devout Tennessean, “this action declared every pulpit vacant and meant that the North had the right to take over our churches with their property.” …

Oath of J. Hicks

Having the oath forced upon them was not the only form of humiliation suffered by former Confederates. Most melancholy to Southerners was the supplanting of their banner with the federal flag. “The saddest moment of my life,” recalled Myrta Avary, “was when I saw that Southern Cross dragged down and the Stars and Stripes run up … I saw it torn down from the height where valor had kept it waving for so long and at such cost.”

“Never before,” added another woman, “had we realized how entirely our hearts had been turned away from that what was once our whole country, till we felt the bitterness aroused by the sight of that flag shaking out its red and white folds over us.” …

Throughout the South, many deeply offended widows crossed the street rather than pass under an American flag, draped over the sidewalk. . .

For returning Rebel soldiers, the order to remove or cover CSA buttons from their uniforms seemed to be rubbing their faces in defeat. Just how strictly these rules were enforced depended upon the fiat of each commanding officer. At New Orleans, Gen. Nathaniel Banks was in charge. Confederates believed that the officer from Massachusetts was particularly vindictive in peace because he had “never won a battle” in war and had been derisively tagged “Stonewall Jackson’s Commissary.” Rebel soldiers in the city were not permitted to congregate in groups of three or more, and black troops were delegated to cut the buttons from their coats. “I saw squads of them dispersing gatherings of Confederates,” recalled a paroled prisoner,” and I saw coats from which the buttons had been cut.” …

Thus, one by one, the victors took possession – body and soul – of the vanquished. Forced to swear loyalty to a hated enemy, their private thoughts censored, their public thoughts punished, the symbols of their nationhood outlawed, their religion and prayers policed – there seemed no haven or sacred ground.”

Hunter Wallace

November 28, 2011