Never Forget the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Between 165 and 300 innocent men, women, and children who were slaughtered at Wounded Knee, South Dakota by murderers that the US government deemed worthy of receiving Medals of Honor for the soldier’s “heroic stance” on the battlefield. Hello!? It wasn’t a Wounded Knee battle but a gruesome massacre!

Between 165 and 300 innocent men, women, and children who were slaughtered at Wounded Knee, South Dakota by murderers that the US government deemed worthy of receiving Medals of Honor for the soldier’s “heroic stance” on the battlefield. Hello!? It wasn’t a Wounded Knee battle but a gruesome massacre!

The Wounded Knee Massacre (also mislabeled as the Wounded Knee Battle) happened on December 29, 1890, where the Miniconjou, Lakota (Sioux) chief Big Foot (Spotted Elk) and some 350 of his followers camped on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Surrounding their camp was a force of U.S. troops, that was alerted to the band’s Ghost Dance activities. It is important to note that this was indeed a massacre, and not the “Wounded Knee battle” as some prefer to call it.

The atmosphere was tense since an order to arrest Chief Sitting Bull just 14 days earlier at the Standing Rock Reservation had resulted in his murder, prompting Chief Big Foot to lead his people to the Pine Ridge Agency for safe haven.

Trouble had been brewing for months. The once-proud “Sioux” found their free-roaming life destroyed, the buffalo are gone, themselves confined to reservations dependent on Indian Agents for their existence. In a desperate attempt to return to the days of their glory, many sought salvation in a new mysticism preached by a Northern Paiute medicine man called Wovoka and the Ghost Dance.

European American Fear of the Ghost Dance phenomenon, led to the Wounded Knee Massacre

Emissaries from the “Sioux” in South Dakota traveled to Nevada to hear his words. Wovoka called himself the Messiah and prophesied that the dead would soon join the living in a world in which Native American Indians could live in the old way surrounded by plentiful game.

A tidal wave of new soil would cover the earth, bury the whites, and restore the prairie. To hasten the event, Native American Indians were to dance the Ghost Damce. Many dancers wore brightly colored shirts emblazoned with images of eagles and buffaloes.

Chief Big Foot (Spotted Elk) lies lifeless in the snow near Wounded Knee Creek following the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890. (also mislabeled as the Wounded Knee Battle)

These “Ghost Shirts” they believed would protect them from the bluecoats’ bullets. During the fall of 1890, the Ghost Dance spread through the Sioux villages of the Dakota reservations, revitalizing the Native American Indians and bringing fear to the whites. A desperate Indian Agent at Pine Ridge wired his superiors in Washington:

“Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy… We need protection and we need it now. The leaders should be arrested and confined at some military post until the matter is quieted, and this should be done now.”

Most European Americans of the time viewed Native American Indian dancing as a threat. Fearing an orchestrated Indian uprising, by the 1870s, both the U.S. and Canada had enacted laws banning the performance of cultural or religious rituals, including dancing.

General Nelson Miles, who was assigned to investigate the Ghost Dance phenomenon among the Plains tribes, issued a warning that if the practice was not stopped, it could lead to an all-out Native American Indian war. In response, the US War Department deployed 7,000 troops to maintain control over the Lakota Oyate.

On December 15, 1890, the order went out to arrest Chief Sitting Bull at the Standing Rock Reservation where Tatanka Iyotake (aka Sitting Bull) was murdered in the attempt. Chief Big Foot was next on the list. When he heard of Sitting Bull’s death, Big Foot (Spotted Elk) led his people south to seek protection at the Pine Ridge Reservation.

General Nelson Miles commanded Major Samuel Whiteside and the Seventh Cavalry to apprehend Big Foot (Spotted Elk) and his followers. The army intercepted the band on December 28 and brought them to the edge of the Wounded Knee camp. The next morning the chief, racked with pneumonia and dying, sat among his warriors and powwowed with the army officers.

General Nelson Miles commanded Major Samuel Whiteside and the Seventh Cavalry to apprehend Big Foot (Spotted Elk) and his followers. The army intercepted the band on December 28 and brought them to the edge of the Wounded Knee camp. The next morning the chief, racked with pneumonia and dying, sat among his warriors and powwowed with the army officers.

Suddenly the sound of a shot pierced the early morning gloom. Within seconds the charged atmosphere erupted as Indian braves scurried to retrieve their discarded rifles and troopers fired volley after volley into the Sioux camp. The often mislabeled “Wounded Knee battle” had started. It wasn’t a battle, it was a massacre!

From the heights above, the army’s Hotchkiss guns raked the Indian teepees with grapeshot. Clouds of gun smoke filled the air as men, women, and children scrambled for their lives. Many ran for a ravine next to the camp only to be cut down in a withering crossfire.

Never Forget when the smoke cleared and the shooting stopped, approximately between 165 and 300 Lakota men, women, and children laid dead (or were dying in the aftermath), Chief Big Foot aka Spotted Elk among them. It is also important to note that approximately 20 soldiers died that day.

“I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream…” ~ Black Elk

The incident was widely reported through the press right after the Wounded Knee massacre, with most articles echoing the government’s public stance about the military’s heroic actions against “bloodthirsty Sioux”. William Fitch Kelley, a Nebraskan reporter, and eyewitness wrote:

“I doubt that either a buck or squaw will be left to tell the tale of this day’s treachery. The members of the Seventh Cavalry have once more shown themselves to be heroes.”

The New York Times referred to Wounded Knee as a “battle,” mentioning little about the murders of women and children. In January 1891 however, a Times editorial observed that the event was “almost uniformly treated as a bloodthirsty and wanton massacre” in European papers.

Some of the criticism about the Wounded Knee massacre targeted federal policy. It was military officers in the field that expressed the harshest criticism toward the incident. Although discouraged by his superiors from doing so, General Nelson Miles called for a court of inquiry into the Wounded Knee massacre.

RELATED: The Wounded Knee Massacre: The Forgotten History of the Native American Gun Confiscation

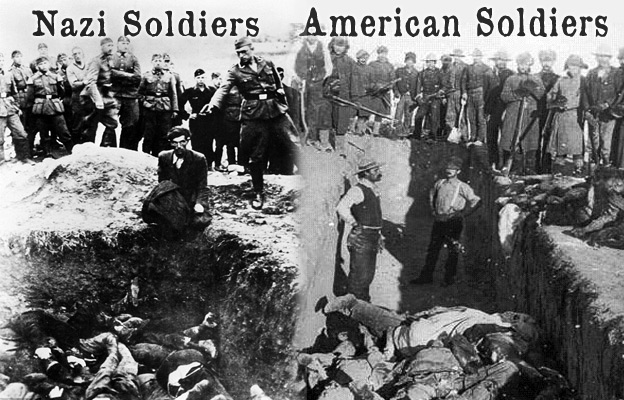

Despite his condemnation, the US War Department awarded 20 Medals of Honor to the soldiers involved in the Massacre of Native American Indian men, women and children at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. The US War Department also erected a monument to honor their fallen soldiers, meaning fallen murderers.

General Nelson Miles subsequently emerged as a prominent champion of justice for wrongs committed toward Native American Indian people at Wounded Knee South Dakota.

In the eyes of most European Americans of the 19th Century, the Wounded knee Massacre was synonym with the end of Native American Indian resistance and the conquest of the West.

For Native people, the tragedy of Wounded Knee 1890 was disgusting proof of the utter disregard of the U.S. Government toward its treaty responsibilities, its duplicity, and its cruelty toward Native American Indian people.

Representatives of the Minneconjou (and now Oglala) and citizens around the world have been advocating for revocation of at least eighteen Medals of Honor, awarded to soldiers who participated in the massacre Wounded Knee 1890.

Honoring the authors of this massacre is a smear upon the honor of all, and diminishes the value of the Medal award to others for their legitimate valor and sacrifice. A proper memorial is needed at Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

One that contains the correct names of the victims (such as Chief Spotted Elk) and leaves out no one. The House and Senate had agreed to support such a memorial in prior resolutions, even while Wounded Knee is a National Historic Landmark, nothing has been done.

Movie trailer about the Wounded Knee massacre

Beginning just after the bloody victory over General Custer at Little Big Horn, (2007) Movie Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee in 1890 intertwines the perspectives of three characters: Charles A. Eastman “Ohiyesa”, a young, Dartmouth-educated, Lakota doctor held up as living proof of the alleged success of assimilation; Sitting Bull, the proud Lakota chief who refuses to submit to U.S. government policies designed to strip his people of their identity, their dignity, and their sacred land – the gold-laden Black Hills of the Dakota people; and Senator Henry Dawes, who was one of the architects of the government policy on Indian affairs (Dawes Act of 1887).

SOURCES: Based on materials compiled from “Massacre At Wounded Knee, 1890” by EyeWitness to History (1998) and “The Truth About the Wounded Knee Massacre” by IndianCountryToday (2016)

Written for and published by I Love Ancestry ~ December 29, 2019