Falling Cloud (aka PFC Ira Hamilton Hayes)

“There they battled up Iwo Jima’s hill,

Two hundred and fifty men

But only twenty-seven lived to walk back down again. And when the fight was over,

And when Old Glory raised

Among the men who held it high, Was the Indian, Ira Hayes ~ Johnny Cash, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”

Fear, without a doubt, is everyone’s inner struggle. When confronted and an ordinary human stands up, rises against the odds and faces the challenge, this ordinary man becomes a hero. For “being terrified but going ahead and doing what must be done―that’s courage” (Piers Anthony, Castle Roogna), and heroes are nothing other than ordinary people who by acting in the heat of the moment can make themselves extraordinary.

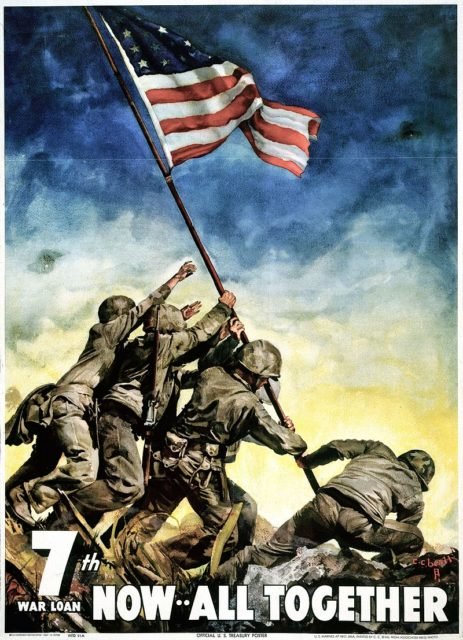

One of the greatest acts of heroism was performed by the simplest of men. Ira Hayes, an introspective 22-year-old Native America from the Pima tribe and a U.S. Marine, on February 23, 1945, in the midst of the Battle of Iwo Jima, was one of the patriot soldiers who raised the U.S. flag atop Mount Suribachi while the war still raged on the volcanic rock. The image captured by photographer Joe Rosenthal became an iconic one, earning him a Pulitzer Prize. As for the story of the heroic Marine, his ended up being one of the saddest stories.

First and foremost, when deciding to write the story of Ira Hayes, one couldn’t find a better way to do it than to begin by quoting Johnny Cash, a brilliant soul who managed to sum up a story so poignantly: “The Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima.”

First and foremost, when deciding to write the story of Ira Hayes, one couldn’t find a better way to do it than to begin by quoting Johnny Cash, a brilliant soul who managed to sum up a story so poignantly: “The Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima.”

Born on January 12, 1923, to a World War I veteran and a Presbyterian school teacher in Sacaton, Arizona, the capital and the very heart of the Gila River Indian Reservation, Ira Hayes was the oldest of six children. He was a quiet and withdrawn boy with an excellent understanding of the English language even when very young.

His devoted mother a full member of the Pima tribe, aspired for her children to be literate and educated members of this new world which they were now unwillingly a part of, and made sure this was the case.

In 1932, Ira and his family were forced out of their home–“The white man’s greed,” sang Johnny Cash–and relocated 12 miles northwest to Bapchule, where Ira continued his education at the Phoenix Indian School. Still the same shy Pima boy, he was an excellent student. Former classmates would say, “Ira wasn’t like the other guys. He was shy and never talked to us girls” and his family would describe him as “quiet, and somewhat distant.” He was a type of person who seemed to be immersed deep in his own thoughts, one who wouldn’t speak unless he is spoken to.

But when he did speak it was of was his determination to enlist in the United States Marine Corps. He felt it was his duty to assist his homeland and fellowmen in dire need following Japan’s shocking military strike on Pearl Harbor. He joined the Marines on August 26, 1942. He was 19 years old and ready to prove his worth.

The shy boy rose to the challenge and endured the rigorous military discipline. Not just that, he volunteered to be a “paramarine,” a paratrooper. In no time he came to be known amid the unit as “Chief Falling Cloud” and a respected Private First Class among his soon to be brothers in arms at the Parachute Marine Training School at Camp Gillespie in San Diego. He was called into action and along with the silver “jump wings” attached to his uniform was shipped to the South Pacific in Noumea, New Caledonia, as a fully trained parachutist and distinguished member of the Marine Corps.

From then on he was shifted back and forth from the Guadalcanal and San Diego in what were two major battles for him and his fellow soldiers that lasted for 11 months up until February 19, 1945, when every surviving man deemed ready for battle was dropped on the southern side of Iwo Jima. They were to join a large contingent of approximately 70,000 Marines that landed on the island earlier that morning, in “Operation Detachment.” It was a last man standing effort to capture a strategic point near Japan’s mainland.

From then on he was shifted back and forth from the Guadalcanal and San Diego in what were two major battles for him and his fellow soldiers that lasted for 11 months up until February 19, 1945, when every surviving man deemed ready for battle was dropped on the southern side of Iwo Jima. They were to join a large contingent of approximately 70,000 Marines that landed on the island earlier that morning, in “Operation Detachment.” It was a last man standing effort to capture a strategic point near Japan’s mainland.

The volcanic island of 21 square miles was one of the strongest military strongholds for Japan and the Allies wanted to prevent them from using it. Furthermore, they saw it as the best possible rallying spot from where they could advance their invasion of Japan’s mainland.

It was the first ever ground assault for the U.S. Marines on Japanese home ground and it wasn’t going to be easy. It was estimated more than 20,000 Japanese soldiers were present but concealed, placed out of sight in an underground network of pits and tunnels dug beneath the highest peak on the island, Mount Suribachi. The rest were stationed in bunkers carved into the mountain itself, making it look like a heavily fortified and armed mountainous Motte Castle of the middle ages. It had to be taken down, so with all of their forces the allies struck at its heart from the very beginning.

Many of the Marines died. Probably more than should have on their advance toward the mountain peak. However, after four days of blood splatter and relentless battle, some of the fiercest days recorded in the history of war, the Marines were close and picked 40 men tasked to climb the highest spot, place a telecommunication line, and most importantly, raise the American flag for everyone still fighting bellow to see it waiving.

The U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia

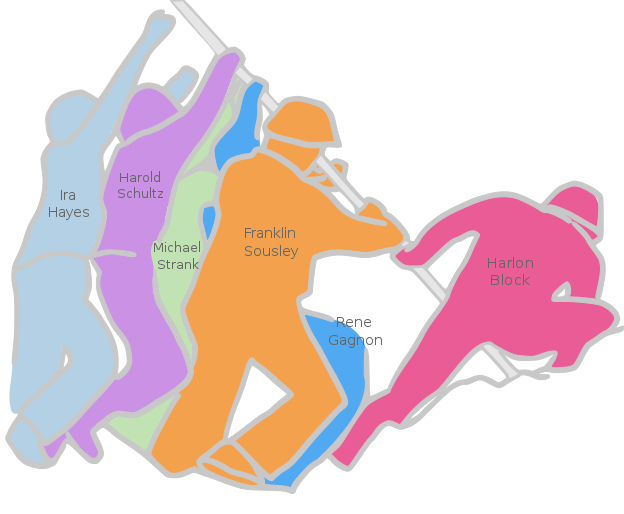

The same day, on February 23, 1945, six of them survived the uphill stretch and placed the flag in the manner as it was captured by Rosenthal, the war photographer who by only recording a tiny fraction of a second, immortalized the men. While we all know the picture that came to be the iconic representation of America’s hard-won victory and probably the most powerful symbols of patriotism among its citizens today, almost no one knows much about the boys raising the flag. They might have won Joe Rosenthal the Pulitzer, and inspired Felix de Weldon to sculpt the Marine Corps War Memorial that is now standing beside the Arlington National Cemetery, but it brought nothing but death or misery for the young men.

Seventh-War-Loan-Drive-Poster (May 11–July 4, 1945)

Harlon Block, a farm boy from Rio Grande, Texas. Franklin Sousley from Eastern Kentucky, a boy who never really had a father and had lived as a grown man as early as eight years of age. Mike Strank, a Czechoslovakian immigrant and a coal miner in Pennsylvania. Rene Gagnon from Manchester, New Hampshire, a descendant of French Canadian parents. John “Jack” Bradley, a paramedic from Antigo, Wisconsin, and father to James Bradley who recently, upon discovering his daddy’s post-war letters, wrote and published the book Flags of our Fathers, which Clint Eastwood adapted into the critically acclaimed movie of the same name in 2006.

Three of them died on the way down: Strank, Sousley, and Block, who according to Bradley was still waiting his very first kiss, died in combat in the following days. As for Hayes himself, the Indian boy deemed a non-citizen on his own land, he left the war uninjured but with a head loaded with the sorrowful memories of his dead brothers and an image of a mass graveyard he left behind.

Three of them died on the way down: Strank, Sousley, and Block, who according to Bradley was still waiting his very first kiss, died in combat in the following days. As for Hayes himself, the Indian boy deemed a non-citizen on his own land, he left the war uninjured but with a head loaded with the sorrowful memories of his dead brothers and an image of a mass graveyard he left behind.

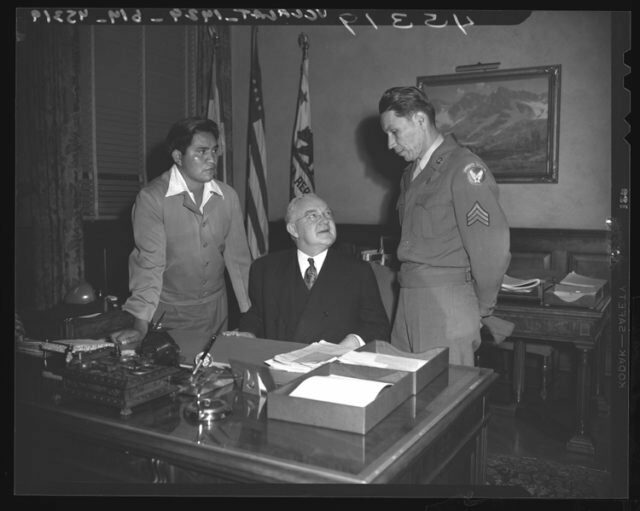

Ira Hayes (left) with Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron (1947)

After the end of the war, one would think that after such unspeakable horrors, survivors would be taken care of and offered solace. In need of national heroes, the military sent the three survivors on a sort of tour. They were carried from town to town and paraded through the streets of no less than 32 cities. With many awarded medals as honorary gratifications for his sacrifices, but without proper care for the trauma he had suffered, Ira was left to cope alone and with the feeling of guilt trapped inside. For he was alive and celebrated as a hero for only raising a flag, while so many mothers and fathers were shedding tears over their deceased kids that died doing much more. Most of all he was feeling betrayed and deserted by the same nation he solemnly swore to protect.

Unable to find peace of mind nor a steady job and with no one to provide him comfort, understanding, or therapeutic guidance, Ira drowned his sorrows in alcohol and became a drifter, a loner who found himself behind bars. He was found dead on the pavement near his home in Arizona on January 24, 1955, only 32 years old. It was no more than 10 years since he famously raised the American flag on Mount Suribachi.

Hayes’s headstone in Arlington, Virginia.

But in between those years, this war veteran, marked as drunk and alcoholic by society, made one inspirational Forrest Gumpian barefoot walk of no less than 1,300 miles from his home in Arizona right to Harlon Block’s home in Texas, only to tell his family that their son, who was controversially mistaken with a Sgt. Hank Hansen, was the actual frontman holding the flag in the iconic image. He had tried to tell the military of the mistake in identification, but no one wanted to listen.

Anyhow, that is the sad story about the shy Pima Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima, and if Johnny Cash started it, it is best if he finishes it:

Call him drunken Ira Hayes, He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinkin’ Indian

Nor the Marine that went to war.

Written by Martin Chalakoski for the Vintage News ~ January 8, 2018

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE:

Pingback: Haille’s Comet | Metropolis.Café