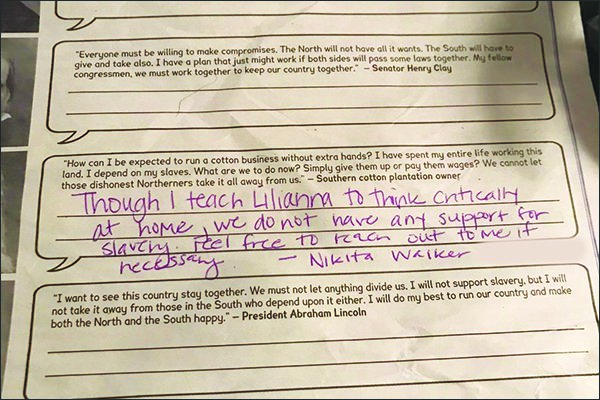

A parent in Rutherford county, Tenn., refused to let her daughter complete this assignment in a Studies Weekly publication, which asked students to write from the perspective of a plantation owner. — Image from Facebook post

When Nikita Walker, a parent in Rutherford County, Tenn., saw that her daughter’s homework asked the then-5th grader to write a few sentences in support of slavery, she was confused—and angry.

Walker’s daughter was given the assignment last year in an issue of Studies Weekly, a national social studies publication that presents lessons on history, government, and society in a newspaper format, designed to be consumed week-by-week.

The activity instructed her to write from the point of view of several Civil War-era actors, including a southern cotton plantation owner. Walker told the teacher that her daughter, who is black, would not be completing the assignment. “You’re teaching them the horrors of slavery, and then you’re asking them to give three pros for slavery?” she said in an interview with Education Week.

Walker was angry with the teacher, but also with Studies Weekly. “What editor was like, this is a good idea?” she asked.

Her concern comes at a time when there is a growing call for schools to acknowledge the United States’ history of racism and oppression, and elevate the voices of groups of people who have been marginalized since this country’s founding. Recent campaigns have pushed schools to remove the names of Confederate leaders, and some districts have resurfaced debates about how to describe well-known historical events and figures.

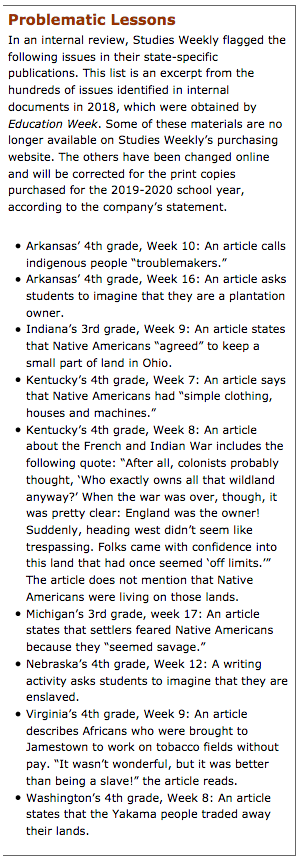

The article Walker identified wasn’t an isolated incident. An internal review of Studies Weekly’s widely used materials found more than 400 examples of racial or ethnic bias, historical inaccuracies, age-inappropriate content, and other errors in the materials, according to internal documents that were presented to the company’s executive board, which were recently provided to Education Week. The staff review team flagged about 100 as high-priority fixes, which included biased language or age-inappropriate content, such as descriptions of graphic violence, according to these documents. The review took place during the 2018 calendar year.

The article Walker identified wasn’t an isolated incident. An internal review of Studies Weekly’s widely used materials found more than 400 examples of racial or ethnic bias, historical inaccuracies, age-inappropriate content, and other errors in the materials, according to internal documents that were presented to the company’s executive board, which were recently provided to Education Week. The staff review team flagged about 100 as high-priority fixes, which included biased language or age-inappropriate content, such as descriptions of graphic violence, according to these documents. The review took place during the 2018 calendar year.

As part of the process, the company convened a diversity board, made up of K-12 administrators and social studies directors, education and history professors, and advocates, all but one of whom did not work for the company. This board reviewed incidents flagged as high-priority and made suggestions as to whether changes needed to be made, according to internal documents.

Many of the issues identified in that review concern Native Americans or enslaved people. Some lessons asked students to espouse the views of plantation owners, or write from the perspectives of slaves. Examples in other lessons include describing Native Americans as “troublemakers,” saying that they “seemed savage,” and stating that tribes agreed to trade away their lands to white colonists.

“We have a tendency to either erase or whitewash our difficult history, and this seems to be an excellent example of the way that starts,” said Maureen Costello, the director of Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, who reviewed examples of flagged issues at Education Week’s request. “We start laying down these false narratives in elementary school.”

The company says that it has changed and reprinted some of these materials and removed offending articles online. Other articles that included these issues, such as the Arkansas 4th grade and Kentucky 4th grade curricula, were pulled from the online store only after Education Week inquired about the review process.

“All of these issues are a concern for history and social studies publishers because social awareness is an evolving mindset,” the company said in a statement emailed to Education Week, attributed to the executive team.

“Many of our products had gone to press while our diversity board was reviewing them,” the statement reads. “Since that time, we have made improvements, replaced identified publications, and reprinted revisions of others for the 2019-2020 school year.”

Finding Inaccuracies

Studies Weekly, a Utah-based curriculum company founded in 1984, sells social studies curriculum for grades K-8 and science curriculum for grades K-5. More than 13,000 schools across the country, with about 4.3 million students, use Studies Weekly, according to the company’s website. Eight states have adopted its materials, including Alabama, California, Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas.

The review process focused on the company’s social studies materials, which include “newspapers” with articles, activities, and writing prompts.

In February 2018, the company came under fire for an article included in a 5th grade publication. The short fiction, titled “Cotton-Pickin’ Singing,” told the story of a white girl, Alana, and a black boy, Jackson, who were magically transported back to Georgia in the 1700s. Alana explains the history of slavery to the boy in a passage that includes several historical inaccuracies—including the false statement that white colonists didn’t also enslave Native Americans. As she talks, Alana directs Jackson to pick cotton to appease the overseer. Parents in the Monroe County, Ind., school district voiced concerns about the lesson, and, as a result, the school board ended its contract with the company.

That year, the company started an internal review process of their content—and assembled the external diversity board to assist in the work.

In discussing the need for the board, Studies Weekly CEO John McCurdy said that what is considered acceptable language is different today than it was in the 1980s and 90s, when Studies Weekly was a new company. Now, he said, “You don’t call people slaves, you say they were enslaved. It’s political correctness, and it’s sensitivity monitoring, and those kind of things.”

As a result of the review process, some articles have been changed and will be reprinted with updates, he said. The company also decided to discontinue some articles and write entirely new publications for those states. If teachers call in asking for these publications, they will be able to purchase online-only versions—with the offending articles removed, McCurdy said.

“You’ve got teachers out there that are like, ‘If you guys don’t have something for me, I don’t have the time to go create new stuff myself,’ ” he said. “Teachers are swamped. And so they wanted it.”

Time constraints stalled the updating process, which will pick up again in July, said McCurdy. The company had to divert time to creating new publications for several state adoptions, and as a result not all of the flagged issues were addressed, he said in an email to Education Week.

Education publishers do periodically update textbooks and other materials. But because of adoption timelines and purchasing cycles, these changes in the publications often don’t reach schools right away. And it can be a logistical challenge to quickly correct a problem or error.

In 2015, for example, a Texas high school student found a caption in a McGraw-Hill textbook that described enslaved Africans as “workers.” At the time, there were 100,000 copies of the book in the state, NPR reported. In this case, McGraw-Hill decided to ship corrected copies to schools for free or provide additional materials—a sticker to cover the caption in the book, and a lesson plan about the language.

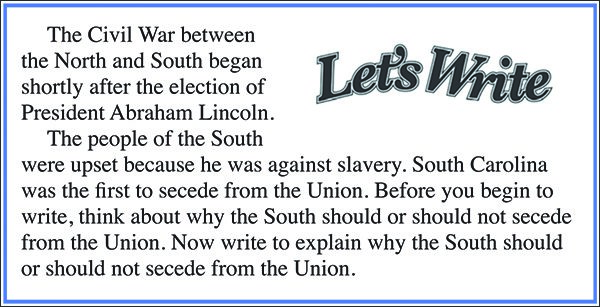

In their emailed statement, the Studies Weekly executive team noted that a revised weekly unit would be mailed to all of the customers who ordered the Florida 4th grade curriculum, which includes an activity that asks students to argue for or against secession.

The diversity board’s work had also halted. The company’s chief product officer told the board in an April 10 email it was disbanded, and the members received no further assignments. However, they received a second email recently from McCurdy stating that the board’s work would continue. That email was sent after he spoke with Education Week on June 7.

Framing Historical Narratives

Several patterns emerge among the articles that the company flagged as problematic during the review process.

Many articles, as described in documents created by the review team, which were obtained by Education Week, include historically inaccurate or misleading information about the relationship between white colonists and indigenous people.

Some of these materials are no longer available on Studies Weekly’s purchasing website. The rest have been changed online and will be corrected for the print copies purchased for the 2019-2020 school year, according to the company’s statement.

A lesson in one of the company’s Florida publications gives students the option to argue for secession. A 2018 review conducted by Studies Weekly found hundreds of issues of bias and inaccuracies in their publications. — Excerpted from Studies Weekly’s Florida 4th grade curriculum

Articles in Indiana’s 3rd grade curriculum and Washington’s 4th grade curriculum state that Native Americans agreed to trade away their lands. That framing obscures the contentious history of land rights in these areas, said Costello of Teaching Tolerance. “War was often made on tribes,” she said. “The treaties were also problematic, because they often were coerced. False promises were made [by the U.S. government].”

The trends in Studies Weekly materials reflect the broader erasure of Native people in U.S. history curriculum writ large, she said. “We don’t really ever grapple with the fact that we invaded this land, and then we proceeded to enslave and exploit an entire group of people.”

Other articles about Native Americans describe tribes as aggressive and primitive. An article in the Arkansas 4th grade curriculum calls indigenous people “troublemakers,” while an article in the Kentucky 4th grade publication states that Native people had “simple clothing, houses and machines.”

“Statements that describe indigenous cultures as ‘simple’ reflect Eurocentric views that are woefully out of step with current historical knowledge,” said Sam Wineburg, a professor of history at Stanford University, in an email.

Other flagged articles concern slavery. Some ask that students take on the perspective of slavery advocates. Florida’s 4th grade publication includes an activity that gives students the option to argue in favor of seceding from the Union to protect slavery. Others, like Nebraska’s 4th and South Carolina’s 3rd grade curricula, ask students to imagine that they are enslaved.

Simply asking students to imagine the perspective of a slaveholder doesn’t give them the tools to understand the past, said Stephanie P. Jones, an assistant professor of education at Grinnell College in Iowa. Instead, she said, teachers can ask students to interrogate primary sources.

And activities that ask students to pretend they’re enslaved can be harmful for students of color—including students who are descended from enslaved people, said Jones. “Why do we always have to emulate ourselves at the worst part of our lives?” she asked.

Acknowledging a Problem

Walker, the Tennessee parent, also raised concerns about this kind of perspective-taking. After calling and emailing Studies Weekly about the writing exercise in her 5th grader’s work with no response, Walker posted on Studies Weekly’s Facebook page in August 2018. A reply from the company on its page noted that it was working with the diversity board to remove “dated and offensive content.” The section had been removed online, the comment read.

The incident made her worry about what her son, who will be starting 5th grade soon, might see in the publication. “It just kind of strengthened why it’s so important for me to teach my kid history at home, and especially black history,” said Walker. “There’s no way that I trust this company to tell them anything about it.”

Lavora “Gayle” Gadison, a member of the diversity board that had been assembled to review flagged issues and propose changes, said that the Studies Weekly materials that she saw shared many of the same problems she sees in social studies curricula nationwide. Gadison is the social studies curriculum manager at Cleveland city public schools.

In general, she said, lessons objectify enslaved people and teach slavery in isolation without showing how American racism stems from justification of the institution. Materials don’t explain that slavery was perpetuated because it was profitable for white people—including the founding fathers. “The stories [in Studies Weekly] were no more objectionable than the stories that we find in other U.S. history textbooks,” said Gadison, whose district uses Studies Weekly. Gadison said the company was progressive for even looking at these issues. “At least there was a start there, and at least there was an acknowledgment—it was acknowledged that there was a problem.”

Costello of Teaching Tolerance noted that the issues identified by Studies Weekly in their review are not specific to elementary social studies and history curricular materials. Misrepresentations of Native American history and reenactments of slavery can be found in K-12 classrooms across the country, she said. “The fact that they’re reinforced in a textbook series is awful. But they’re handed down as the air we breathe,” Costello said.

But a review like this should be an opportunity to set the record straight, said Costello. “It’s a lesson in historiography. The way we interpret history changes as we learn more.”

Jones, the Grinnell professor, said that some of the onus is on districts, schools, and teachers to critically examine the materials they’re handed. Teachers need to be shown how to be “interrupters” of bias or racism in materials, she said.

“There are very few elementary school teachers who have much background in social studies,” said Costello. Most are either reading or math specialists. “Very, very, very few of them either majored or minored in history,” she said. “They tend to replicate what they were taught.”

Written by Sarah Schwartz for Education Week ~ June 14, 2019