Publisher’s NOTE: For me, what you are about to read has been a fascinating journey – partially because I spent 12 or 13 years of my youth growing up in the ‘burbs about 25 miles north of the Chicago Loop. Even with the amazing teaching of Mr. Adair in the 5th grade, I was not aware of the history nor the monument dedicated to our Brothers from down South. Oh no, no – I am not speaking of the Brutha’s who have probably died in the 32nd Street and Cottage Grove area in modern times – I speak of the ancestors who fought the Second American Revolution. Oh – I guess some of you still call it the Civil War. Well children – no war was ever civil, so just hush yo’ mouth…

When I came across the first part of what lays before you, I was instantly drawn in – but it has sat in my folder for quite some time, but then the second part was placed at my feet just two nights ago – and that was it – it was time to edit and publish this amazing story – and yet – given the topic – it is disgusting as well, but it is our history.

So sit back and breath it in – keeping in mind that the first part of the journey is a bit jaded, due to the Nawth’n way of looking at things? – but the second part gets to the meat of reality. What REALLY went on in this 80 acres of pure Hell? – Oh – and by the way, in 1970 my wife (then fiance) and I went to a birthday party one night around 32nd and Cottage Grove – and we were the only White folks in the ‘hood.

I’ll see you at Sundown…

Prisoners of Camp Douglas

When Chris Rowland’s co-worker told him that Chicago was once home to a Civil War prison camp, he almost didn’t believe it. But a bit of Googling led Chris to a name, Camp Douglas, and a location, Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. It also led him to the camp’s gloomy history, one that included dismal living conditions and a death toll that numbered in the thousands. Beyond that, though, Chris, a 36-year-old sales engineer at a South Side manufacturing company, found hardly any information about the camp. So he came to Curious City for help:

Why was there a prison camp in Chicago during the Civil War and why did so many people die there? What happened to it?

Camp Douglas was one of the largest POW camps for the Union Army, located in the heart of Bronzeville. More than 40,000 troops passed through the camp during its nearly four years in operation. What’s more — and this is where it gets gloomier — it’s been hyperbolically remembered by some historians as the “deadliest prison in American history” and “eighty acres of hell.” So the fact that Chris, despite his earnest attempt, didn’t find much on Camp Douglas interested Curious City, too. How could one of the deadliest Civil War prison camps virtually disappear from our collective memory? Answering this part of Chris’s question had us consider how a city acknowledges the darker parts of its past and the benefits, if any, of remembering them at all.

Why Chicago?

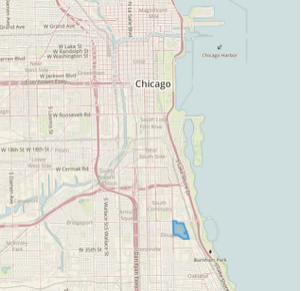

Located on the South Side of Chicago around 31st Street between Cottage Grove Avenue and present-day Martin Luther King Drive, Camp Douglas occupied roughly four square blocks — about 80 acres total — and operated from 1861 to 1865. Back then the area was the country, outside the city limits. Today, it’s Bronzeville.

When it opened in 1861, Camp Douglas was a training and enlistment center for Union soldiers, a pit stop or starting point for soldiers headed to the battlefield. In other words, it had been improvised, and wasn’t meant to hold prisoners or last more than a couple years. After all, no one thought the Civil War would go on as long as it did.

But then, in February 1862, Ulysses S. Grant captured roughly 5,000 Confederate soldiers in a victory at the Battle of Fort Donelson at the Tennessee-Kentucky border. With nowhere else for the captured troops to go, Camp Douglas became a Union Army prisoner-of-war camp, and it stayed one for the duration of the war.

As it turns out, Chicago’s role as a transportation hub made it an ideal location first for a training camp and, later, for a prison. Eight railroads crisscrossed the region in a spaghetti soup of tracks that allowed goods to move to and fro. Young men could travel from various parts of the state to enlist. From there, the Union Army would assemble regiments and brigades and ship soldiers by rail to the front lines.

What’s more, the camp’s location was directly off the Illinois Central Railroad. At the time, this was the longest railroad in the world, running from Cairo, Illinois, along the Ohio River, to Chicago. History buffs may recall that at the beginning of the war Cairo was General Grant’s staging location for Union attacks on the Confederacy. Once he captured Confederate troops, they were only a steamboat and train ride away from Camp Douglas.

What’s more, the camp’s location was directly off the Illinois Central Railroad. At the time, this was the longest railroad in the world, running from Cairo, Illinois, along the Ohio River, to Chicago. History buffs may recall that at the beginning of the war Cairo was General Grant’s staging location for Union attacks on the Confederacy. Once he captured Confederate troops, they were only a steamboat and train ride away from Camp Douglas.

“Camp Douglas was Chicago’s principal connection to the Civil War,” says Theodore Karamanski, a history professor at Loyola University in Chicago and the author of Civil War Chicago: Eyewitness to History.

‘Eighty acres of hell’

Camp Douglas’ makeshift nature showed in its rickety wooden barracks and crude sewer system. Soon, though, the camp was taking on more and more prisoners and keeping them for longer and longer. But because neither side intended on taking large numbers of prisoners for extended periods of time, Camp Douglas — as well as most other Civil War prison camps — proved unprepared to handle them.

“That is when all the prison camps got a lot nastier,” Karamanski says.

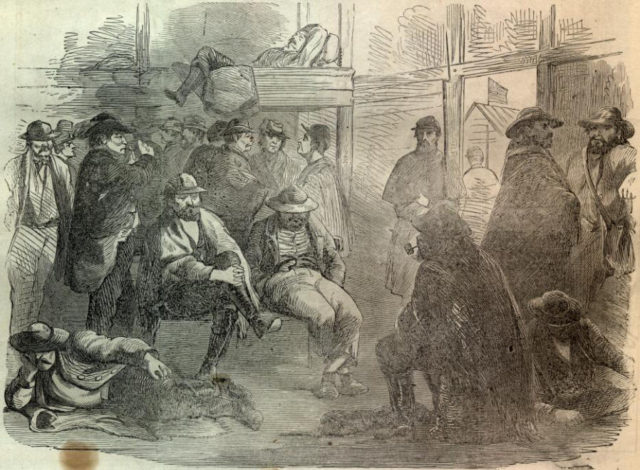

The camp was meant for no more than 6,000 prisoners, and as its ranks grew to roughly 12,000 at its peak it became more dangerous than any battlefield. Overcrowding and poor sanitation spread diseases such as dysentery, smallpox, typhoid fever and tuberculosis. Illness became the camp’s leading cause of death, claiming roughly 4,500 Confederate soldiers, or 17 percent of the total number of men imprisoned at the camp during its nearly four years in operation, according to Karamanski’s estimate. In his book, Karamanski cites an 1862 report by the U.S. Sanitary Commission, wherein an agent admonished Camp Douglas for its “foul stinks,” “unventilated and crowded barracks,” and “soil reeking of with miasmic accretions” as “enough to drive a sanitarian to despair.”

Hundreds of Confederate prisoners of war at Camp Douglas, 1864. (Chicago History Museum)

Karamanski estimates that during the Civil War only one in three soldiers died on the battlefield. The rest died in prison camps or camps of their own army.

“Disease was rampant in Camp Douglas and it was rampant in the Civil War. More people in the Civil War died of diseases than from bullets,” says David Keller, the managing director of the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation and the author of a forthcoming book about the history of the camp.

Still, Karamanski is quick to refute the claim that Camp Douglas was “the deadliest prison camp in America,” as some historians claim. “Civil War prison camps were terrible,” he said. “All of them were terrible.”

While Camp Douglas may have claimed more Confederate lives than any other Union prison camp, it pales in comparison to Andersonville, a Confederate prison in Georgia that offered neither barracks nor fresh water to its Union prisoners. In all, 13,000 men, or 28 percent of the total prison population, perished there, Karamanski says.

Given these details, it’s probably no surprise that escapes occurred regularly at the camp. Many escape attempts were made by digging tunnels into the soft, swampy ground, but most came from bribing the guards. It is estimated that roughly 500 prisoners escaped from Camp Douglas one way or another.

Again, security was lax because the camp had never been intended to hold prisoners. “They barely had any kind of wall up,” Karamanski says. “Some of the prisoners would just wander off and say ‘Hey, let’s go get a drink.’” Drunk and emaciated soldiers (still wearing their Confederate garb), would be picked up by local police and hauled, stumbling, back to the camp.

Camp Douglas as local spectacle

When Camp Douglas was first opened, Chicagoans had free access to the site. Above, visitors with picnic baskets arrive at the camp. (Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum)

When Camp Douglas was first opened, Chicagoans had free access to the site. Above, visitors with picnic baskets arrive at the camp. (Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum)

Recall that Chris, our question-asker, could find little about the camp — as though the place had become a secret. Secrecy was certainly not the case during the war, though. In the camp’s early days, Chicago residents were allowed free access to the camp. “People were excited that here was the enemy, tamed, incarcerated and for your viewing,” Karamanski says. Sometimes, though, visitors — likely Confederate sympathizers — would end up walking out with a prisoner.

Soon, though, the camp tightened up security and stopped admitting visitors.

At that point, a local businessman got an idea. Utilizing a hotel across the street from the camp, he built a viewing platform where he charged customers 10 cents a pop to climb a stairway up to a wooden platform to catch a glimpse of the rebels. “It was a real treat for a lot of kids to see those Confederates,” Karamanski says.

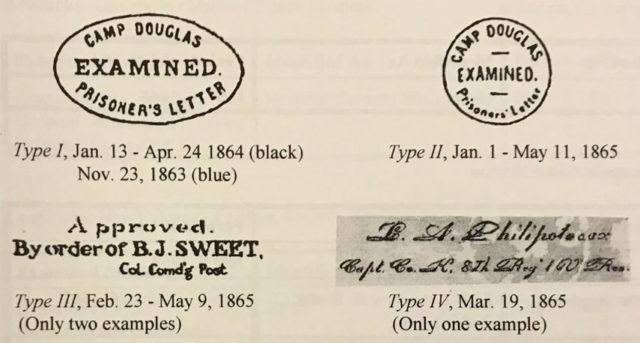

Prisoner Mail from the American Civil War by Galen D. Harrison published in 1997 by Thompson-Shore Inc. Letters mailed from Camp Douglas

When the Civil War concluded in the spring of 1865, Camp Douglas’ prisoners were given a set of clothes and a one-way train ticket out of the city. The camp itself was razed, rather quickly, by scavengers as well as the government, selling off the equipment as surplus.

When summer rolled around, though, the camp parade ground gave way to a new sport that returning union soldiers had learned during wartime: baseball.

“Soldiers came back from the war and they’d lost a lot of their youth,” Karamanski says. “Some of the first baseball games by Chicago’s elite teams were played at Camp Douglas. … It helped erase some of the memories of the war.”

But Karamanski suspects baseball may have helped erase part of a larger memory, too: public memory, or in this case, the way a city tells the story of itself.

For the most part, the history of that memory nearly had Camp Douglas written out.

Remembering the forgotten

A monument in Oak Woods Cemetery at 67th Street and Cottage Grove marks the largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere, or where roughly 4,000 Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Douglas are buried. (WBEZ/Logan Jaffe)

When we first meet Chris, our Curious Citizen, it’s a bitterly cold day in late January and we stand on what Keller and others claim is the largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere: a mound of roughly 4,000 Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Douglas, now buried at Oak Woods Cemetery at 67th Street and Cottage Grove. (The soldiers had originally been buried in City Cemetery, now Lincoln Park. But soon after the war, the city thought better of placing the dead so close to Lake Michigan — Chicago’s principal source of drinking water. That cemetery was closed and the Confederate soldiers were moved to Oak Woods, the only cemetery that would accept them.)

When we first meet Chris, our Curious Citizen, it’s a bitterly cold day in late January and we stand on what Keller and others claim is the largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere: a mound of roughly 4,000 Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Douglas, now buried at Oak Woods Cemetery at 67th Street and Cottage Grove. (The soldiers had originally been buried in City Cemetery, now Lincoln Park. But soon after the war, the city thought better of placing the dead so close to Lake Michigan — Chicago’s principal source of drinking water. That cemetery was closed and the Confederate soldiers were moved to Oak Woods, the only cemetery that would accept them.)

A monument in Oak Woods Cemetery at 67th Street and Cottage Grove marks the largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere, or where roughly 4,000 Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Douglas are buried.

Staring up at the forty-foot-tall bronze and granite memorial where a despondent-looking Confederate soldier stands atop a granite column, bowing his head in remembrance, Chris asks: “So why do you think it was forgotten about? Why was it swept under the rug?”

First off, the Great Chicago Fire came just six years after Camp Douglas closed, sapping resources and shifting the city’s priority away from the South Side. Then came the Great Migration, where hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrated North on the same railroad that once transported soldiers from Camp Douglas to the front lines of the Civil War. When they arrived in Chicago, African Americans began settling in Bronzeville. It’s safe to say probably the last thing on their mind was exploring their neighborhood’s lost history, centering on those who had previously fought to keep them enslaved. Then came the post World War II housing shortage and the urban renewal of the 1960s. “There was a lot of reason to forget about it,” Keller says of the camp.

But at the center of this question of why Camp Douglas was forgotten is the obvious tension of an African-American neighborhood and a city rooted in Union ideals taking steps to remember thousands of dead soldiers who fought on the side to uphold slavery.

“I don’t think you can’t ever discount the impact of race on Chicago memory,” Karamanski says. “So when dealing with the memory of oppression and racism — which is what the Civil War represents — it’s never going to be something that’s broadly consensual because it’s a felt history.”

And that strife over how to remember what happened at Camp Douglas didn’t come about over time. There was deep-rooted animosity toward the Confederate cause from the moment the war ended.

In 1895, the night before President Grover Cleveland and his entire cabinet presided over the dedication of the memorial in Oak Woods, the monument was defaced by vandals. Later, a private citizen erected a more permanent protest, which still stands; just yards away from the memorial to the dead rebel soldiers a large granite marker honors those Southerners who resisted secession as “martyrs of human freedom.”

The issue reared itself again in 1992, when The Commission on Chicago Landmarks proposed to make the Oak Woods mound a historic landmark, drawing the ire of black alderman. “Here is a group of people who looked upon my people as animals, as subhuman,” then-Alderman Allen Streeter told the Chicago Tribune. “I’d rather forget about the whole thing,” he added.

The first official acknowledgment of Camp Douglas was erected in the fall of 2014 outside of Ernie Griffin’s former funeral home at 32nd Street and Martin Luther King Drive in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. (WBEZ/Logan Jaffe)

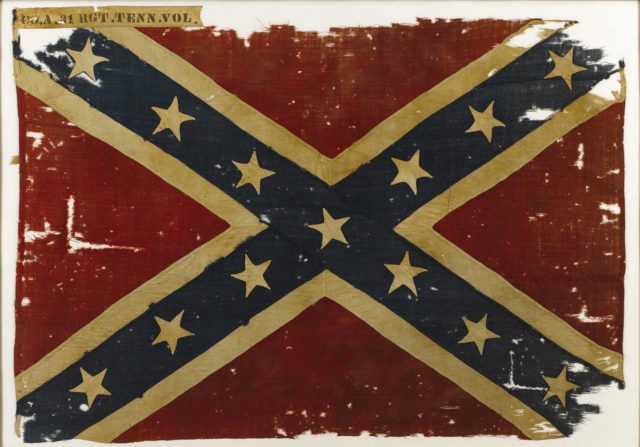

That’s the same year that Ernie Griffin got involved. He ran the Griffin Funeral home at 32nd Street and Martin Luther King Drive — right smack on the former camp’s site. The African-American funeral operator learned his grandfather had enlisted in the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry at Camp Douglas. Griffin decided, much to the neighborhood’s chagrin, to erect a memorial to honor the dead rebels. It included a Confederate battle flag flown at half-mast. “This was like an incitement to many African Americans,” Karamanski says. After the flag kept getting torn down, Griffin took out an ad in the Chicago Defender, the city’s African-American newspaper. In his book, Karamanski quotes Griffin, saying, “The flag is not a symbol of hate. It is a symbol of respect for a dead human being.” Griffin has since died, and the memorial was taken down when the funeral home closed in 2007.

That’s the same year that Ernie Griffin got involved. He ran the Griffin Funeral home at 32nd Street and Martin Luther King Drive — right smack on the former camp’s site. The African-American funeral operator learned his grandfather had enlisted in the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry at Camp Douglas. Griffin decided, much to the neighborhood’s chagrin, to erect a memorial to honor the dead rebels. It included a Confederate battle flag flown at half-mast. “This was like an incitement to many African Americans,” Karamanski says. After the flag kept getting torn down, Griffin took out an ad in the Chicago Defender, the city’s African-American newspaper. In his book, Karamanski quotes Griffin, saying, “The flag is not a symbol of hate. It is a symbol of respect for a dead human being.” Griffin has since died, and the memorial was taken down when the funeral home closed in 2007.

Remembering the cost of victory

According to Karamanski, one of the most important things to keep in mind while trying to preserve history is the way we tell stories about the past … as well as who tells them.

“If we try to memorialize Camp Douglas in such a way that we don’t share the story, share the authority in creating the site with the people in the community, then you’re asking for trouble,” he says.

It’s a lesson being considered by Bernard Turner and David Keller, directors of the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation, which plans to build a museum somewhere on the site of the former camp. Keller says they are “very, very close” to being able to announce a location.

“I think it’s important to know what’s in your neighborhood,” says Turner.

“I think it’s building community pride,” adds Keller.

After the rocky attempts to memorialize Camp Douglas and the soldiers who died there, seeking to remember Camp Douglas has been going more smoothly lately. In 2014 the foundation helped persuade the Illinois Historical Society to erect the first official acknowledgement of the camp: a small plaque at 32nd Street and Martin Luther King Drive informing residents and passersby that they are in fact walking upon significant history. The foundation’s also included the local public school, Pershing East, in its various projects, which include two archeological digs of the site. And it has discussed its efforts with the DuSable Museum of African American History.

Sherry Williams, president of the Bronzeville Historical Society, says it’s important to remember Camp Douglas as not only a prison camp, but also a place where black union soldiers and confederate prisoners intersected. (WBEZ/Logan Jaffe)

For Sherry Williams, president of the Bronzeville Historical Society, there’s potential in telling stories about Camp Douglas that move beyond its brutal legacy.

“We look at the Camp Douglas story as being told just about the miserable conditions that were faced by these prisoners of war, but there are wider stories to need to be expounded on,” she says. “It’s not one narrative, it’s multiple narratives.”

One such narrative hits close to Williams. After looking into the camp’s death records, she discovered that a soldier named S.G. Cooper died at the camp. He was a Southerner whose family owned her direct ancestor, Nero Cooper, a former slave who enlisted in the Union’s African-American infantry.

“There’s a tie between Confederate soldiers and the Union black soldiers,” Williams says. “Here’s the intersection of the fight for freedom.”

Still, Karamanski says, it’s okay if the way we remember Camp Douglas is kind of dark.

“I think it’s true that Camp Douglas is a dark shadow on Chicago’s history. But it also reminds us what the Civil War was about,” he says. “You didn’t go ahead and end slavery without a fight. But we’re honest only if we really understand the cost that victory — of saving the union and ending slavery.”

Chris Rowland, Curious Citizen

Chris Rowland is a 36-year-old sales engineer at a South Side manufacturing company. He lives in Uptown and was reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin when he got to thinking about the Civil War and what connection Chicago might have to it.

Curious Citizen Chris Rowland, right, at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. (WBEZ/Logan Jaffe)

The topic then presented itself at work. “One of the guys mentioned that there was actually a prison camp in the actual city in Chicago,” he says. Except, “nobody could remember what the actual name of it was.”

He says one of the guys thought the name might have been Camp Burnham. Another guy thought the camp was called the Andersonville Prison, confusing the name of Chicago’s North Side neighborhood with the famous civil war prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia.

But when Rowland searched a bit more on Google, he learned about the camp’s real name, but not much else. When he submitted us this question about a year and a half ago, he says he was surprised at how difficult it was to find any information about Camp Douglas.

And though he’s not a Chicago-native — or a history buff, he says — learning more about Camp Douglas, Chicago and the Civil War has put a bit of his own life into perspective.

“I grew up in Oklahoma,” he says. “We weren’t even a state yet.”

The above was written by Meribah Knight for WBEZ 91.5 Chicago ~ March 11, 2015

Eyewitness’ Report on Camp Douglas

“The rules and regulations of the prison, which had been adopted by the military authorities, were strict, and rigidly enforced… The strict enforcement of these appeared to be all that was required by the commanders of the post; but some few of the police guards adopted, or at least enforced some of the most silly and frivolous rules which could have been thought of, and made the prisoners pay the penalties for their violation by the most villainous and inhuman methods of punishment.

“The rules and regulations of the prison, which had been adopted by the military authorities, were strict, and rigidly enforced… The strict enforcement of these appeared to be all that was required by the commanders of the post; but some few of the police guards adopted, or at least enforced some of the most silly and frivolous rules which could have been thought of, and made the prisoners pay the penalties for their violation by the most villainous and inhuman methods of punishment.

“These different punishments would be administered for the most frivolous and insignificant offenses which could be imagined and the prisoners would hardly ever know, or have any idea what offense had been committed. Most of these different punishments would be inflicted after night, in the barracks, and sometimes during the day. The Big Four … Old Red, Prairie Bull, Little Red and Old Bill McDermott were the prime executioners.

“After the signal given at 6 p. m. for the prisoners to retire, we had to do so without delay, and were not allowed to speak or whisper to each other under any circumstances, but had to go to sleep, and then be very careful as to how loud we slept. When any of the prisoners were heard by the guard to whisper or talk, he would call for the one who did the whispering or talking, and if the right one could not be definitely located, all the prisoners occupying the barrack would be marched out to Morgan’s Mule, forced to mount and ride from two hours to half a night, barefooted, and with no covering on them save their thin and ragged clothing. Many of the prisoners were so thinly clad they could scarcely hide their nakedness. The latter part of the winter of 1864 and first part of 1865, were extremely cold, and the Federals complained of its severity, and stated that the weather was the coldest which had been known for several years.

“Another favorite method of punishment was this: Every man in a barrack would be marched out on the snow in front of the barrack, formed in a line of one rank, and then told by the guards “that under the snow and ice could be found plenty of corn for them to parch and eat, that they must reach for it,” which was done in the following manner: The guards would point their pistols, cocked, at the heads of the prisoners, make them bend their bodies over in a stooping posture, until the tips of their fingers would touch the ground under the snow and ice, the knees having to remain perfectly stiff and straight and not bend in any manner. They would be compelled to stand in this position from half an hour to four hours, and never for a shorter time than half an hour, the snow and ice being very deep all winter, often twenty inches. This was called, by the guards, “reaching for corn,” or “reaching for grub.” Frequently many of those who were being punished in this way would become so exhausted and fatigued they would fall over in the snow in an almost insensible condition; these were apt to receive a flogging with a pistol belt, administered by the guard, or receive several severe kicks and blows. Often these men would stand in that position until the blood would run from the nose and mouth; the guard would stand by and laugh at it.

Hanging Prisoners by the Thumbs,” at Camp Chase and Johnson’s Island by Joseph Barbie, 1868

“Another favorite method was to tie prisoners up by the thumbs. This was accomplished by tying a strong cord around each thumb, then throwing one end over a scantling or beam above the head, drawing the cord until the arms and body were stretched until the toes would just touch the ground or floor. Prisoners tied up in this manner frequently had to remain suspended until life was almost extinct, before the guards would cut them down. I have seen the blood run from the nose and mouth of some who were thus punished. This punishment often compelled those upon whom it was inflicted to lie in bed for several days, unable to walk.

“There was still another favorite mode of gratifying their insatiate thirst for punishment. They would procure half of a barrel or large box, have a hole made in it large enough for the prisoner’s head to slip through, and so as to let the barrel or box rest on the shoulders; when this ornament was placed over the prisoner’s head he was forced to walk from one end of the street to the other, from half a day to a whole week every day continually. This was very severe punishment. The barrel or box was very heavy, and all the time pressed on the shoulders with nothing to protect them, which made the carrying of very painful and annoying.

“Still there was another mode, differing from all the others, but fully as harsh and severe, if not worse. The guards would procure a ladder long enough to reach from the ground to the top of the plank wall which enclosed the prison grounds, the upper end of the ladder resting against the side of the parapet and the lower end on the ground just over the dead line. The prisoner would be compelled to climb up and down the ladder from morning till night, every day for a whole week, and sometimes longer; he was not allowed to stop and rest at all. One prisoner had to climb and descend this ladder for nearly a whole month. The only time that any rest could be obtained would be during meal time and at night. He was in charge of the sentinel on the parapet, and if he stopped to rest would have been shot. This tried men’s souls, as well as their constitutions.

“Often if only one man was taken out to be punished, he would be stripped naked to the waist and given from fifty to one hundred lashes with a broad pistol belt on the naked back, so severe that the blood would trickle down the back to the heels. If a barrel was convenient, the prisoner would be stretched across it; if not convenient, then he would be stretched across the foot of a bottom bunk and whipped.

Title Page

“Just outside the kitchens, slop barrels were always kept for the purpose of depositing beef bones, and such other scraps and refuse as came from the kitchens; these would often remain until late in the afternoon without being removed and emptied. The hungry prisoners often resorted to these barrels in search of a beef bone from which to make soup, or bake by the heating stoves in order to obtain the grease. Whenever either or all of the “big four” caught any of the prisoners near the barrels, or would see any prisoner with a bone, they would make him take it in his mouth, get down on his hands and feet, go up and down the street from one end to the other, and bark like a dog, or imitate it as near as possible, the guard all the time laughing at the prisoner and keeping a pistol cocked at his head ready to fire. The “big four” called this the dog performance, or barking like a dog. Sometimes the “big four” would allow the prisoner to stand up and walk erect from one end of the street to the other, carrying the bone in his mouth; at the same time they would take their stand at some convenient place within range of the prisoner, in the event that an army pistol became necessary to be used as a persuasive means to enforce this method of punishment.

“It was death to cross the dead line. This dead line was placed around the walls of the prison, for the purpose of keeping any one from approaching the walls. A prisoner after reaching the plank wall could easily tunnel out and escape, and while tunneling could not be seen by the guard on the parapet, hence the object of the dead line. If a prisoner approached near the dead line, or stepped over it, either by accident or on purpose, he would be fired upon sure, and quickly reminded that he was on forbidden ground by the sharp crack of a Springfield rifle and the dull thud of a minie ball piercing his body through. If the sentinel on the parapet failed to fire at him, some one or more of the “big four” would do so, and they rarely missed their aim. ”

SOURCE: A Sketch of the Battle of Franklin, Tenn.; with Reminiscences of Camp Douglas, by John M. Copley, 1893. This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

LINK TO FREE E-BOOK: https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/copley/copley.html

CSA 31st Reg. Tenn. Volunteers Battle Flag

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

Pingback: In Memorium: Ex-Slave and Confederate, dies at 112 | Metropolis.Café

Confederate soldiers did not fight for slavery because they couldn’t even afford a slave. That’s merely the lie perpetrated by a divisive entity with an interest in destroying America as we know it. ~ Deo Vindice