Problem Is Three Times Worse in Traditional Schools

Empty Classroom In Elementary School. (Photo By: Education Images/UIG via Getty Images)

Teachers in traditional district schools are three times as likely to be chronically absent from the classroom as those in charter schools, meaning they are gone for more than 10 days in a typical 180-day school year, a new research paper has found.

In all, 28.3 percent of teachers in traditional schools, compared with 10.3 percent in charters, miss that much time, according to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a right-leaning education-focused think tank, in a study on teacher absenteeism nationwide released Wednesday. The totals include both sick and personal days.

“If you look at the gap between the two sectors,” said David Griffith, the report’s author, “there’s a very clear link between state collective bargaining laws and the number of days teachers are entitled to, and teacher chronic absenteeism.”

Given the threat posed to unionized schools in many cities by charters, which are often staffed by uncertified and non-unionized teachers, the report’s sometimes eye-popping comparisons seem likely to further divide education advocates.

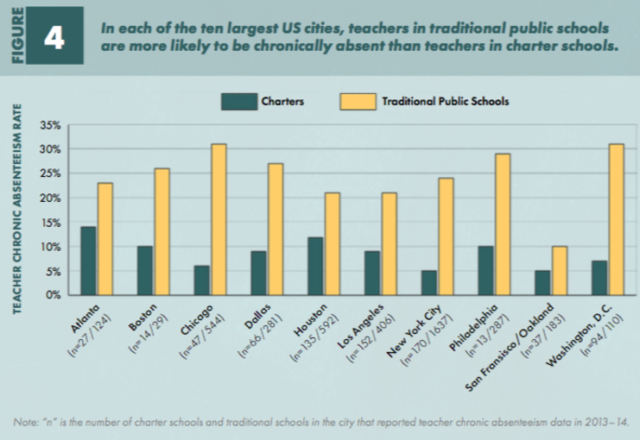

Drawing from federal sources as well as databases maintained by charter and teacher groups, Fordham identified a wide range in chronic absenteeism rates — from 15 percent of teachers in Utah’s traditional schools to 79 percent in Hawaii. But in 34 of 35 states with at least 10 charter schools, and in the nation’s 10 largest cities, traditional schools employ a higher percentage of chronically absent teachers than charters do.

Sometimes much higher. In 12 states, teachers in traditional schools are twice as likely as those in charters to be chronically absent; they are four times as likely in another seven states, including New York and Florida, five times as likely in New Hampshire, and six times as likely in Nevada.

The gap in cities is much the same, with chronic absenteeism four times as likely among teachers in traditional schools in Washington, D.C., and New York City, with 1.1 million students, the country’s largest public school district, and five times as likely in Chicago.

(Courtesy of Fordham Institute, “Teacher Absenteeism in Charter and Traditional Public Schools”)

Teacher absenteeism lowers student achievement and the motivation to attend and participate in school, researchers have found. One study estimated the effects of having a substitute to be equivalent to replacing an average teacher with one in the 10th to 20th percentile of productivity, with larger effects in the days before exams.

Teacher absence also incurs billions in costs for substitutes, disrupts common planning time, and, in often forcing other teachers to cover for absent colleagues, detracts from those teachers’ preparation for their own classes.

The contrasts in absenteeism are particularly provocative when focused on teachers governed by union-negotiated contracts. There is no demonstrated connection between collective bargaining and chronic absenteeism, Fordham notes, but gaps between traditional and charter schools are smallest in right-to-work states like Georgia and Texas that prohibit teacher unions from negotiating agreements.

In Alaska, the only state where there’s more chronic absenteeism in charters (33 percent, compared with 30 percent among traditional schools), charters are governed by the same collectively bargained contracts as their districts.

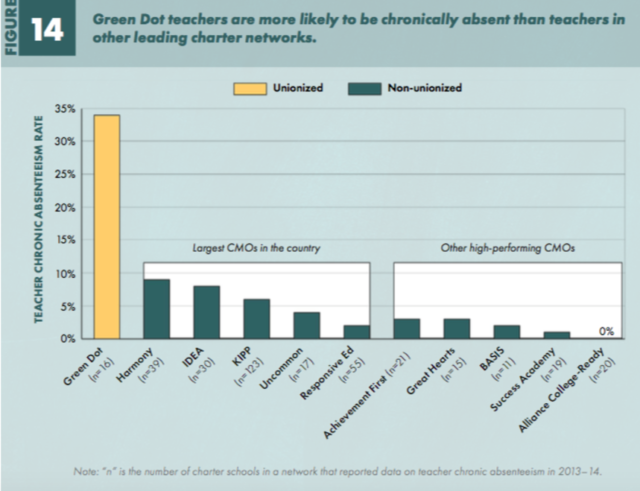

Perhaps more dramatically, teachers in the small fraction of unionized charters nationwide were twice as likely to be chronically absent as their peers in non-unionized charters, 17.9 percent to 9.1 percent. The study reported that teachers in Green Dot charter schools, probably the country’s best-regarded unionized network, have a 34 percent chronic absenteeism rate. That’s higher than the traditional schools in Los Angeles (21 percent), where most Green Dot schools are located, almost seven times as high as the city’s other charters (which are at 5 percent), and between four to 17 times as high as the largest and highest-achieving charter management organizations nationally.

(Courtesy of Fordham Institute, “Teacher Absenteeism in Charter and Traditional Public Schools”)

On Wednesday, Green Dot provided more recent records, from the 2015-16 school year, that it said reflected lower rates than those reported by Fordham. “Green Dot California has a chronic teacher absenteeism rate of 6% which is comparable with other CMOs in California and across the country,” CEO Christina de Jesus and Angel Maldonado, head of its teachers union, said in a statement. “We are of course, committed to further reducing chronic absenteeism in all of our schools.”

Sick and personal day policies vary considerably, from a total of five in Texas to 25 in Hartford, Connecticut. While the report can’t make causal connections, Griffith suggested that teachers in schools with better sick and personal day benefits may have incentives to miss more time. Studies have found that “absenteeism is influenced by prevailing group absence behavior at the school,” and teachers who come into high-absenteeism schools are likelier to have more absences.

“Teachers are human, they’re going to respond to incentives like anyone else does,” Griffith said. “If you give them more days, it’s logical to expect they will take more days, even if they don’t take all of them.”

By contrast, the Fordham analysis suggests that in schools like higher-achieving charters, which have closely prescribed behavioral codes, deep commitment to the school’s philosophy, and no tenure protection, teachers will be less like likely to miss school.

Researchers have also found teacher absenteeism to be greater in schools with concentrations of poor students; surprisingly, Griffith found that demographic factors had only marginal effects on absence rates at the state and national levels.

While suggestive, the report’s findings aren’t definitive. Available data didn’t allow Fordham to measure chronic absenteeism among non-tenured traditional school teachers, who are younger and probably closer in age to many charter teachers and who also lack job security. Fordham can’t disaggregate among teachers by age at all or by school grade taught, so we don’t know whether high school teachers miss more days than kindergarten teachers. (Better data might provide some solace to Green Dot, whose schools are all middle and high schools.)

Nor do we know the actual number of days absent teachers missed, which is important because, as the report mentions, the distribution of chronic absences — whether the typical chronically absent teacher is out for 12 days, for instance, or more — would enable more accurate distinctions between schools and the types of schools. That, in turn, might dull the report’s traditional-versus-charter gloss.

A 2014 National Council on Teacher Quality study of teacher attendance in 40 urban districts, cited in the Fordham report, found that 16 percent of teachers who’d been absent for 18 school days or more accounted for a third of all absences in the districts. Another 16 percent who were out for three days or less accounted for just 2 percent of absences.

In addition, it’s true that the average teacher misses about eight days a year while the average American worker misses 3.5 days, despite having 20 percent to 25 percent more workdays. And it’s also true that only 7.7 percent of workers in other industries who have access to paid sick leave are absent for more than 10 days. But comparing teachers with other unionized workers would be more helpful, as would comparisons with those in other high-stress occupations: police and firefighters, or perhaps nurses, rather than accountants and lawyers.

The problem of students chronically missing school has historically drawn more attention than teacher absenteeism: Fordham observes that a dozen states made reducing student absence a measure of school quality in accountability plans required under the Every Student Succeeds Act, with many more considering it. For good reason: a 2012 analysis by Johns Hopkins University and the National Governors Association found chronic absenteeism to be among the strongest predictors to identify future high school dropouts — stronger even than suspensions and test scores.

Fordham points out, however, that it will be difficult to fix student absenteeism without ensuring their teachers are regularly in class. “State leaders, why not pay as much attention to teacher absenteeism in your ESSA plans as you do to student absenteeism?” Fordham asks. “How far can we get by fixing the second problem if we don’t fix the first?”

Written by David Cantor and published by The 74 ~ September 20, 2017

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml