“It was as if my long-term students and I were taking a long journey by ship and it was my fault that, in the parlance of the controversial education law, William was being left behind.”

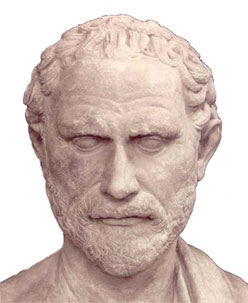

Eugène Delacroix: Demosthenes Declaiming by the Seashore

A single event can awaken within us a stranger totally unknown to us. To live is to be slowly born. ~ Antione de Saint-Exupery

Chapter 21 ~ Awakening

I couldn’t help smiling as I watched my new student, twelve-year-old William, running laps around the school field, one hand clutching his baggy pants to keep them from slipping inexorably toward his feet. This ten minute run was the energetic beginning of the two-hour class we called main lesson.

In spite of his trim, athletic physique, William ran in a lopsided and lackadaisical manner that, together with his ridiculously low-slung pants, had initially led me toward the admittedly judgmental conclusion that William’s sloppiness in appearance probably meant carelessness in his character. But, I reassessed my initial impression after talking with his mother who revealed surprising details about William’s morning ablutions and his painstaking selection of jeans and tee shirts.

Now, as I looked more carefully, I saw that William actually worked hard to be impeccable. Immaculate from head to toe, he sported a practiced, bouncy walk and I learned from William himself that his wide-cut, low-slung trousers that exposed just a touch of plaid boxer shorts had been the Armani equivalent in his peer group at his previous school. I noticed that each hair was in place and that he wore the perfect combination of jewelry and a charming smile.

I tried to put myself in William’s place when he joined our fifth and sixth grade class as a sixth grader, traveling toward our Cape Cod school from his neighborhood just outside New Bedford, passing forests of white pine and an occasional flooded cranberry bog. Was he apprehensive each time he reached the apex of the Bourne Bridge, spotting our two-story brick building framed by trees in the foreground and Buzzard Bay and Vineyard Sound glistening in the distance?

Did he pause before stepping out of the car to ask his mother for the umpteenth time why she had decided to separate him from his friends to send him to this school?

Did he pause before stepping out of the car to ask his mother for the umpteenth time why she had decided to separate him from his friends to send him to this school?

William was sociable with his classmates, but in class he seemed protected by a personal reserve. He did not participate in singing or group poetry recitation and he never raised his hand to offer an observation or an answer. Then, one day, unexpectedly, the class clown in him took a chance and he responded to a question with an impudent comment. By the end of the week his ability to execute a swift but temporary mutiny had won him a new position among his classmates. During our lessons, when he would offer a remark, all heads would turn and, for a flash, I would feel bereft as my authority was usurped by a charismatic twelve-year-old child.

I felt suddenly on shaky ground. I wasn’t used to this. I knew that none of my long-term students would consider making an impolite remark in class. I knew this with certainty, for I knew my students well. Their tendencies, their proclivities, their academic and personal strengths and challenges had soaked into my consciousness over many years of lessons, recesses, class discussions and personal conversations.

I had also taken up a more formal study of my students by learning how to observe students during group explorations called ‘child studies’ in our weekly faculty meetings. Here we worked to discover the individuality of children and I came to see how important it was to notice such things as how each child walked and how tightly they gripped my hand in greeting every morning. It had been my job to lead my students onpath toward wonder, but my own wonder grew out of my growing understanding of each of them.

My observations during each school day continued to be deepened by an evening meditation on each child. Just before preparing my lesson for the following morning I would close my eyes and bring a picture of each student into my inner vision. Sometimes this would be a snapshot from our day together, and sometimes the image would be an inner impression, a sense of the child’s developing soul. This contemplative attention had brought each child into my mind’s eye night after night, year after year, until I felt him or her to be an integral part of my very being.

In contrast, I knew little about William. So I tried to play catch-up, to watch, to listen, to try to understand what worried him, what motivated him. I knew that William had learned how to be impeccable in a culture that valued loose jeans, gold chains and visible underwear. Now he was struggling to find some manner of comfort in what he termed a “weird school” in a room of kids with hopelessly unfashionable “tight pants” and a strange propensity for taking their teacher seriously.

Now, after five years with my class, my students had become like family. One of the many advantages of such a relationship was the ability to carry traditions and activities from one school year to the next. One of the class’ favorite non-competitive games involved standing in a circle and creating and solving math problems in a rhythmic sequence. The first child might offer “five times” and the next child might say “three is” and the third child had to answer “fifteen” while keeping the beat. The next student might say “twenty minus,” then the next child “thirteen is” and the answering person said “seven.” The rhythm was supported by finger snapping by all, and, when we were on a roll, knees would bounce, shoulders sway and smiles would erupt as a student looked perplexed, and then gave the right answer just in time to keep the rhythm going. We played this number game round and round the circle for many minutes during each main lesson.

It hadn’t always been this smooth. When we started this daily activity during the previous school year, we were far from rhythmic. Some number facts seemed elusive. Certain students were weak on the higher times tables. Often students didn’t pay close attention and did not hear their cues. Our progress had lurched along unevenly. We laughed, then fixed mistakes. Everyone worked on becoming more focused. Memories improved. By the end of that year we had become good at this number game. My kids never spoke of their sense of accomplishment, but a few weeks after William joined us in the fall of 1996, they returned my confident smile one fall morning when I said, “five times” and turned to my neighbor.

I asked William to watch until he understood the rules. He knew his number facts, but, when he stepped into the circle, he refused to attempt the rhythmic pattern that made this activity so much fun. He could often be seen bouncing down the hall to the beat of a whispered rock song, so I knew that his rhythmic sensibilities went far beyond what was required for this simple math game. But, when it was his turn, he did not pick up the beat. Instead, he paused, looked at his feet and our group dynamic slowed until he muttered the correct number, then resumed again. William’s attitude here reminded me of his sloppy approach to running. However, now that I had moved beyond judging, I saw that William wasn’t careless. He was embarrassed. This odd activity was not cool at all. I could see now that, for William, the only saving thing was that his friends from his old school were not watching him play this silly game.

I was concerned that the class might be impatient with William for messing up our hard earned arithmetical perfection. So, I was relieved when they offered him understanding, generous smiles. I also carried this patient, protective gesture toward William. Above all, I wanted to spare him any additional embarrassment. So, while I freely offered advice and suggestions to my long-term students, I did not share most of my critique of William’s work, his manner or his behavior. This forbearance had the affect of increasing my attention. Each time I held back a suggestion that William join us in singing, restrained a reprimand about looking out the window or withheld an invective about actually listening to the twenty- five minute lessons I delivered from memory each day, my awareness of William intensified so that, over time, William came to occupy much of my attention.

An observer in my classroom might have judged me to be too complacent about William’s lack of progress, might think I had given up on him. Perhaps an experienced teacher watching me with William would have thought my approach to him was lazy or incompetent. I knew this because an impatient voice in my own mind questioned everything I did and, in William’s case, everything I did not do.

This voice prodded me to impose plans that would quickly bring William into compliance. It asked, “Shouldn’t you consider tutoring? Don’t you remember the class you took on educational psychology as an undergraduate? Wouldn’t behavior modification, a carefully designed system of rewards, be the best way to reach a kid like William who comes from a very different schooling environment? Shouldn’t you start now by showering praise on William each time you notice a small success? Why not try to compliment each slight improvement in handwriting or give him a smile and a pat on the back for a correct answer to a math problem? Shouldn’t you call his parents to enlist their help in motivating William through punishments and incentives? Can you really expect that a twelve-year-old, who is already a rebel against all things academic, will, on his own, without intense prodding of some sort, evolve, perhaps magically, into an eager learner?”

This impatient inner voice that wanted me to do something active to prod William argued constantly with my inner impulse toward patient observation and threw in a measure of guilt to make sure I was paying attention. However, my patient tendencies ruled with stubborn determination. I justified my laconic approach by recalling another student’s challenging transition into our class culture.

Jeremy had come to our class the previous year, at the start of fourth grade, with wide eyes, an easy smile and a willingness to participate that matched the intensity of William’s reluctance. Jeremy was a natural at all sports, and, within his first week, had become an integral member of the group that streamed down the stairs and out to the kickball game at the bottom of the recess hill.

Teachers at Jeremy’s past school had seen him as a well-adjusted achiever, and I too had come to appreciate his stunning academic competence. But I had worried about Jeremy almost as much as I now worried about William.

William had a habit of shunning all but minimum involvement in the teacher-defined aspects of our school. In his previous school he had invested himself in peer-defined contests regarding dress and behavior, including scorn for teachers and the work they assigned. In contrast, Jeremy had learned how to work steadily and successfully in all subjects.

While William was likely to tip his chair back, stare out the window, then glance at a blank notebook, Jeremy had leaned over his desk, muscles tense, his hand moving steadily across the page. In his quiet, focused concentration he was similar to most of my long-term students. The room silent, with everyone sinking into concentration, Jeremy would raise his hand. I would motion to him to bring his notebook to the front of the room where I knew he would say something that I rarely heard from my other pupils. Laying the book on my desk, he always uttered the same words, “Is it good?”

It was always good, really good.

While his classmates worked steadily without seeking my approval, Jeremy asked for my evaluation many times each day. He was used to gold stars, letter grades and frequent praise. Seeing that Jeremy felt lost without such supports, I gave him the encouragement he needed. But I hoped that, like his classmates, he would soon find that learning provides its own rewards.

It was Jeremy’s research for a report about the ginkgo tree that led to a transformation. I never knew whether it was the medicinal properties of the gingko leaves, the fact that the tree is its own species, the unusual shape of the leaves or, all of this together that was the spark that ignited Jeremy’s interest. He convinced his parents to help him buy and plant a gingko tree in their yard and, as he delivered his oral report, I heard a new eagerness in his voice. When he finished speaking, he appeared satisfied. He did not ask,” Is this good?”

I wanted William to discover the gift of wonder and to find that he could feel engaged in learning. I wanted him to have his own equivalent of Jeremy’s ginkgo tree. I did not want to replace William’s apathy with an orientation towards rewards, with a feeling that he worked for me rather than for himself. Yet, it was clear that William’s ginkgo equivalent would never be found if he continued to seclude himself in his own private world during class time.

During my daily storytelling, William appeared to be unmovable. He didn’t laugh at the funny parts or react to dramatic moments. He never volunteered to take part in our tradition of reviewing the story the day after it was told. In the early grades the children usually simply retold the story. Now, my kids were able to condense the story or lesson fairly quickly, then discuss what it meant to them. William’s wooden demeanor during even the most heated discussions convinced me that, even when our conversation sparked with intense controversy, he wasn’t listening.

During the previous school year, Jeremy had made most of his transition into our culture of eager learning over a couple of months. By Thanksgiving I had all but forgotten that he was new to our class. This year, William’s wooden participation had gone on from September through January, through our review of fractions and long division, through Gautama Buddha, many pharaohs, Gilgamesh, the Fertile Crescent, through Odysseus, the parts of speech, through Athens and Sparta. In midwinter he showed no signs of engaging in the substance of our work and I began to wonder whether he would ever get anything out of his time in our class.

My sense of guilt became palpable. My impatient inner voice said, “I told you so” and came close to overpowering my impulse to protect William from pressure. I began to think that it was probably too late for William to allow himself to become interested in history, math or science. After all, he had devoted too many years to learning disengagement, to developing an oppositional relationship to teachers and, as a result, he was likely to be so set in his ways that he could not change without energetic interventions.

My husband had often laughed at the unrealistic optimism that surfaced in me when approaching almost any difficulty. He had even made up his own aphorism that he used when he thought I was being too naïve about the likelihood of success in the face of a daunting problem. Now my impatient voice taunted me with his words.Thinking of my too-little-too-late approach to William, I said to myself “you really did believe that daisies might grow out of the floor.”

It was not only my pig-headed optimism that had caused me to believe that William might, somehow, experience an academic awakening. My graduate school training in the philosophy behind Waldorf education and my five years of classroom experience had steeped me in a perspective antithetical to the behavior modification which I studied as an undergraduate and which stands behind so much of current practice in schooling today. B.F. Skinner, the most famous practitioner of behaviorism, had shown that it is possible to use his methods to teach just about anything to anyone and had demonstrated this by training pigeons to play ping pong. Food was the reward he provided for each step the pigeons took toward ping pong playing. Similarly, a behavioristic approach to human learning provides rewards for defined behaviors, typically in the form of praise and grades.

Those who have invested themselves in this popular paradigm for motivating students have lost sight of the fact that learning is to the soul as food is to the body. Learning is a journey into fantastic new information, amazing skills and growing sense of mastery. Children don’t need external rewards to influence them to be naturally drawn into wondrous experiences and the sense of amazement that comes with growing competence. If the appropriate experience is given at the right time and if children are not distracted by praise and extrinsic rewards, the process of learning engenders a sense of awe, which is the soul’s self-administered reward.

Being a teacher who works consciously with wonder is a lot like being a cook. The art and science of creating an appealing, nourishing meal is similar to the art and science of creating an engaging lesson. To a large extent, knowing the inner needs that are common at each developmental age helps a teacher choose material that will be both nourishing and appealing. Beyond this, just as a parent comes to know the food preferences of all members of the family, truly understanding the interests, learning style and temperament of each child helps a teacher prepare lessons that are both rewarding and nourishing.

Such was the inner talk of my patient self, the voice that was, now, in mid-winter, beginning to sound good in theory but useless in practice. Theory aside, so much of the year had gone by and William had apparently made little progress. Now, my other voice, the impatient voice that had been pushed into the background, stepped forward and announced that what worked for my long term students would not work for William. It was too bad he had not come to our school in first grade and grown in our culture. If I had been more realistic from the start, if I had gone after William’s attention with a bit more vehemence, with the same approach Skinner used with the pigeons, perhaps William would, by now, engage in our work in a productive manner. It was as if my long-term students and I were taking a long journey by ship and it was my fault that, in the parlance of the controversial education law, William was being left behind.

#

As we approached the end of our Greek history block, I realized we were running behind in my curriculum plan. When I do my planning in the summer, I always leave one or two spare, unplanned lessons each month. This way I have flexibility. The detailed research behind each lesson happens the week I am telling it, usually the night before. Sometimes I discover an additional biography that calls out to be told, or I find that the class needs an engaging story to enliven their comprehension of a new concept.

This January, snow days and my diversions had used up the couple of spare days and more. I needed to leave Greece and return to our study of decimals, but I had to do justice to Philip and to his son Alexander. And how would I fit in Demosthenes, the Greek orator who put pebbles in his mouth to perfect his speaking? I decided I could save time by clumping Philip and his rival Demosthenes into one lesson before moving on to a multi-day story about Alexander the following day.

Ready to tell the story of Demosthenes and Philip, I stood quietly before my class of fifteen students in our spacious but drafty classroom. In spite of the many challenges that come with living inside an antique, we loved this almost century old building with its expansive windows and its view of the Bourne Bridge and the upper decks of the largest ships on the canal.

In many ways, the building was like our curriculum, old but good. Interpreting this venerable curriculum in an antique school building makes me feel that I have stepped outside of our high speed, multi-tasking, media-driven electronic age and into a more grounded era. Here, a sense of timelessness envelops the perpetual stream of childhood and provides a platform for taking the leap to bygone ages, today a leap to ancient Greece.

Outside the window I see the Bourne Bridge and cars moving across it ant-like toward Cape Cod. Everyone but William looks at me expectantly. We are ready for that leap. Then the room is gone, the bridge is gone, and we are in Athens looking at a seven-year-old boy who has just lost his father and has been turned over to greedy guardians who steal his inheritance so that he cannot attend school. I am seeing, and more importantly, feeling the story of Demosthenes and transforming that seeing and feeling into words.

“One day Demosthenes went to a courtroom where he listened to a lawyer try to convince more than a thousand jurymen of his point of view. Demosthenes found himself listening so intently that he lost track of time. One hour, then two, then three went by and still he listened. He watched the jurymen listen too. He saw them lean forward with interest and look sad or happy as the orator carried them with the power of his voice. Demosthenes decided that he too would become a lawyer. He went home and began to study right away. He worked so hard that, in only a year’s time, he was able to bring suit against his guardians and win back much of his inheritance.

“One day Demosthenes went to a courtroom where he listened to a lawyer try to convince more than a thousand jurymen of his point of view. Demosthenes found himself listening so intently that he lost track of time. One hour, then two, then three went by and still he listened. He watched the jurymen listen too. He saw them lean forward with interest and look sad or happy as the orator carried them with the power of his voice. Demosthenes decided that he too would become a lawyer. He went home and began to study right away. He worked so hard that, in only a year’s time, he was able to bring suit against his guardians and win back much of his inheritance.

“Soon after he won his case, he made a public speech. He knew his facts, but he mumbled his words and spoke in a flat, uninteresting voice. He was such a poor speaker that people laughed at him. Even his friends said, “Demosthenes, you had better find a new type of work.

“Demosthenes walked the streets of Athens with his shoulders slumped and his head hung low. He was close to giving up. But a small voice deep in his soul told him that he could be a great orator someday if he was willing to work hard to improve himself.

“He set himself to work right away. He knew he had to stop mumbling, but how? And how was he to speak loudly enough to be heard over the roar of a large group of people? He had an idea. He went to the beach where the sounds of the waves roared more loudly than the crowds. He bellowed until the far off gulls could hear him and his throat grew sore. But that was not enough. He reached down and gathered pebbles and put these in his mouth. He tried to speak clearly with the pebbles. At first his mumbling was even worse. But he kept at it and soon his voice was clear even with the pebbles. He practiced like this for days.”

I paused for a moment to gather thoughts about how Demosthenes did become a great public speaker and how he spoke out against Philip. I thought about transitioning to Philip’s story. Then I noticed something.

I paused for a moment to gather thoughts about how Demosthenes did become a great public speaker and how he spoke out against Philip. I thought about transitioning to Philip’s story. Then I noticed something.

William was listening.

Demosthenes, who worked so hard to reach his fellow Greek citizens with his voice, had now reached across the ages to speak to William. And I, who had long practiced the potentially overly optimistic impulse to watch and wait, and had recently come to the brink of giving in to my impatient voice, felt my heart quicken as William took this small, almost secret step toward participation.

I had held back my active management of William for so long that now my entire consciousness, including the patient observer, and my impatient voice, united in a heightened awareness of William and an intention to do whatever I could to sustain his attention. I looked out the window, appearing, I hoped, to enter into a normal pause in storytelling. Actually, this was not a normal pause at all but a moment to create a radical reconstruction of my lesson. Pushing Philip into the next day’s story, I searched my memory for more about Demosthenes, the parts of the story I had planned to leave out just to make time.

Stealthily, I watched William as I told about how Demosthenes built a special practice room below ground where he could work on his skills without interruption. William looked up with interest as I told about how Demosthenes realized that left the room too often to make good progress, so he shaved half his head to force himself to stay in the room because he would be too embarrassed to be in public. I could see William was still with me as I recounted how Demosthenes hung a sword over the shoulder that he tended to raise when speaking.

It was a barely perceptible change, William’s listening. It was like the first sounds of late winter snowmelt, a slow drip from the roof that softly signals the rush of spring.

His classmates had not noticed.

#

That evening I considered why it was Demosthenes who had caught William’s attention. Perhaps it was that Demosthenes and William were truly kindred spirits. Like Demosthenes, William was deeply self-conscious and easily embarrassed and was willing to work hard to gain approval from his peers. Appearance was important to both of them; they both wished to be impeccable. They both wanted to influence others.

Someone who believes that daisies can grow through the floor might imagine that a disaffected student who finally listened to a lesson might already be prepared to take another step. Perhaps the next morning would find William ready to join in our conversation about Demosthenes. Holding a glorious picture in my mind of William’s open, interested gaze, I wondered whether he was ready to take a big leap. Would he be brave enough to speak about Demosthenes in front of the class?

I usually call on volunteers to help retell the previous day’s story, but sometimes I choose a student who has not offered to speak. In spite of the inner movement I had witnessed in William, I guessed he would not volunteer to talk about what he had heard. I wanted to call on him, but I was concerned about putting him on the spot too soon. Perhaps he would be too embarrassed to participate. I imagined him freezing up in front of the class and retreating ever deeper, even farther into himself.

I decided I would follow my instincts in the morning.

Addressing the whole class, I began “Today you will tell me about a famous orator from Athens,” William was looking at me. I took a deep breath and took his open gaze as an invitation. “William”, I said softly, but surely, “Would you come up to the front of the room?” He walked up and I smiled at him as I sat down in his chair. He looked comfortable as he smiled bemusedly at his classmates. “William, I’d like you to tell us what you remember about Demosthenes.” “Who’s that?” he shot back with a wrinkled brow.

Oh no, I thought, I’ve done it now. My impatient voice, my guilt, has teamed up with my tendency to be overly optimistic and now I have pushed William too far, too fast. I was not the only one in the room who thought I might have put too much pressure on William. His classmates, who thought I was breaking our unspoken rule about going easy on William, appeared concerned and confused. In their silence, in their questioning looks, I could hear them saying, “How could you put him on the spot like this?”

I ignored their consternation and my own fears and, optimistically, continued speaking to William:

“The man I talked about yesterday who wanted to become a good speaker, who went to the beach to practice his speaking.” “Oh! that guy!” he said with confident recognition.

Speaking as if he had always stood before the class, immersed in the retelling of a story, William, with a few prompts from me, told us about all the things Demosthenes did to himself, the pebbles, the head shaving, the sword hung above his shoulder. I had the sense he was talking about an admired popular figure rather than a long-dead Greek orator. I watched the class as he spoke. I had known for a full day that William was with us. And now, as William stood before the class speaking with confidence about another person who learned how to speak with confidence, his classmates surreptitiously shared surprised looks while he smashed the image they held of an impeccable, charismatic rebel, an outsider who had captivated our attention but had not truly entered into the life of the class. Optimism, faithful waiting and quiet attention had bought William the time he needed to awaken into our academic journey.

William finished speaking and walked back to his seat as I returned to my place in the front of the room. As he sat down his classmates burst into joyful applause. He smiled a broad, satisfied grin.

William was on board.

This chapter is an excerpt from A Gift of Wonder, A True Story Showing School as is Should Be by Kim Allsup. Click here for information about the book.

Written by Kim Allsup for and published by Growing Children ~ November 21, 2017.

~ The Author ~

~ The Author ~

Kim Allsup’s childhood wonder years inspired her first career as an environmentalist and her second career as a Waldorf teacher. She was the founding staff member of the Buzzard Bay Coalition and a founding parent of the Waldorf School of Cape Cod. A graduate of Brown University and Antioch University (M.Ed), she served as a Waldorf class teacher, on Cape Cod and at the Pine Hill Waldorf School, for 22 years. She is currently a writer, an advisor to teachers and a gardening teacher pioneering the use of school sunhouses. She lives on Cape Cod with her husband and blogs at Growing Children.

She is the author of A Gift of Wonder, A True Story Showing School as it Should Be.