Great teaching has long been seen as an innate skill. But reformers are showing that the best teachers are made, not born

To The 11- and 12-year-olds in his maths class, Jimmy Cavanagh seems like a born teacher. He is warm but firm. His voice is strong. Correct answers make him smile. And yet it is not his pep that explains why his pupils at North Star Academy in Newark, New Jersey, can expect to go to university, despite 80% of their families needing help to pay for school meals.

To The 11- and 12-year-olds in his maths class, Jimmy Cavanagh seems like a born teacher. He is warm but firm. His voice is strong. Correct answers make him smile. And yet it is not his pep that explains why his pupils at North Star Academy in Newark, New Jersey, can expect to go to university, despite 80% of their families needing help to pay for school meals.

Mr Cavanagh is the product of a new way of training teachers. Rather than spending their time musing on the meaning of education, he and his peers have been drilled in the craft of the classroom. Their dozens of honed techniques cover everything from discipline to making sure all children are thinking hard. Not a second is wasted. North Star teachers may seem naturals. They are anything but.

Like many of his North Star colleagues are or have been, Mr Cavanagh is enrolled at the Relay Graduate School of Education. Along with similar institutions around the world, Relay is applying lessons from cognitive science, medical education and sports training to the business of supplying better teachers. Like doctors on the wards of teaching hospitals, its students often train at excellent institutions, learning from experienced high-calibre peers. Their technique is calibrated, practised, coached and relentlessly assessed like that of a top-flight athlete. Jamey Verrilli, who runs Relay’s Newark branch (there are seven others), says the approach shows teaching for what it is: not an innate gift, nor a refuge for those who, as the old saw has it, “can’t do”, but “an incredibly intricate, complex and beautiful craft”.

Hello, Mr Chips

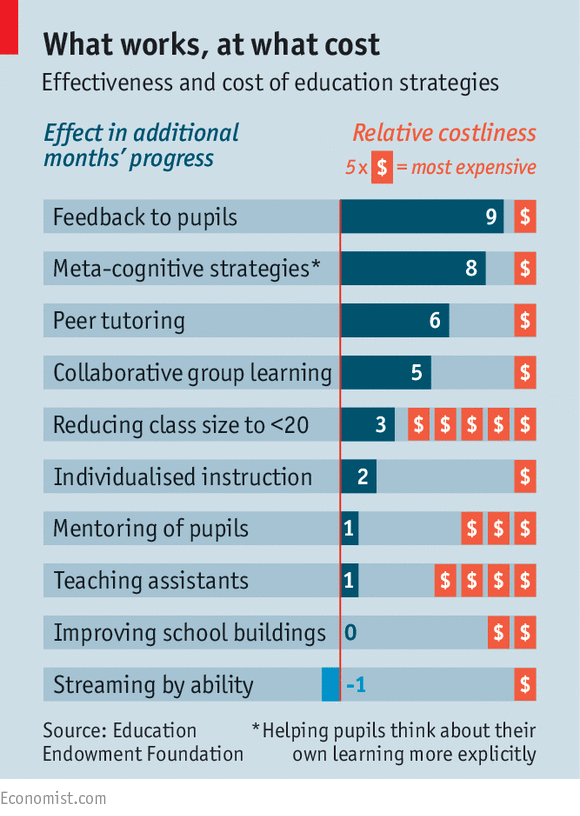

There can be few crafts more necessary. Many factors shape a child’s success, but in schools nothing matters as much as the quality of teaching. In a study updated last year, John Hattie of the University of Melbourne crunched the results of more than 65,000 research papers on the effects of hundreds of interventions on the learning of 250m pupils. He found that aspects of schools that parents care about a lot, such as class sizes, uniforms and streaming by ability, make little or no difference to whether children learn (see chart). What matters is “teacher expertise”. All of the 20 most powerful ways to improve school-time learning identified by the study depended on what a teacher did in the classroom.

Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University, has estimated that during an academic year pupils taught by teachers at the 90th percentile for effectiveness learn 1.5 years’ worth of material. Those taught by teachers at the 10th percentile learn half a year’s worth. Similar results have been found in countries from Britain to Ecuador. “No other attribute of schools comes close to having this much influence on student achievement,” he says.

Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University, has estimated that during an academic year pupils taught by teachers at the 90th percentile for effectiveness learn 1.5 years’ worth of material. Those taught by teachers at the 10th percentile learn half a year’s worth. Similar results have been found in countries from Britain to Ecuador. “No other attribute of schools comes close to having this much influence on student achievement,” he says.

Rich families find it easier to compensate for bad teachers, so good teaching helps poor kids the most. Having a high-quality teacher in primary school could “substantially offset” the influence of poverty on school test scores, according to a paper co-authored by Mr Hanushek. Thomas Kane of Harvard University estimates that if African-American children were all taught by the top 25% of teachers, the gap between blacks and whites would close within eight years. He adds that if the average American teacher were as good as those at the top quartile the gap in test scores between America and Asian countries would be closed within four years.

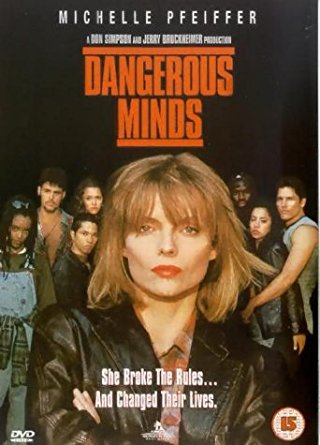

Such studies emphasise the power of good teaching. But a question has dogged policymakers: are great teachers born or made? Prejudices played out in popular culture suggest the former. Bad teachers are portrayed as lazy and kid-hating. Edna Krabappel of “The Simpsons” treats lessons as obstacles to cigarette breaks. Good and inspiring teachers, meanwhile, such as Michelle Pfeiffer’s marine-turned-educator in “Dangerous Minds”, or J.K. Rowling’s Minerva McGonagall, are portrayed as endowed with supernatural gifts (literally so, in the case of the head of Gryffindor). In 2011 a survey of attitudes to education found that such portrayals reflect what people believe: 70% of Americans thought the ability to teach was more the result of innate talent than training.

Such studies emphasise the power of good teaching. But a question has dogged policymakers: are great teachers born or made? Prejudices played out in popular culture suggest the former. Bad teachers are portrayed as lazy and kid-hating. Edna Krabappel of “The Simpsons” treats lessons as obstacles to cigarette breaks. Good and inspiring teachers, meanwhile, such as Michelle Pfeiffer’s marine-turned-educator in “Dangerous Minds”, or J.K. Rowling’s Minerva McGonagall, are portrayed as endowed with supernatural gifts (literally so, in the case of the head of Gryffindor). In 2011 a survey of attitudes to education found that such portrayals reflect what people believe: 70% of Americans thought the ability to teach was more the result of innate talent than training.

Elizabeth Green, the author of “Building A Better Teacher”, calls this the “myth of the natural-born teacher”. Such a belief makes finding a good teacher like panning for gold: get rid of all those that don’t cut it; keep the shiny ones. This is in part why, for the past two decades, increasing the “accountability” of teachers has been a priority for educational reformers.

There is a good deal of sense in this. In cities such as Washington, DC, performance-related pay and (more important) dismissing the worst teachers have boosted test scores. But relying on hiring and firing without addressing the ways that teachers actually teach is unlikely to work. Education-policy wonks have neglected what one of them once called the “black box of the production process” and others might call “the classroom”. Open that black box, and two important truths pop out. A fair chunk of what teachers (and others) believe about teaching is wrong. And ways of teaching better—often much better—can be learned. Grit can become gold.

In 2014 Rob Coe of Durham University, in England, noted in a report on what makes great teaching that many commonly used classroom techniques do not work. Unearned praise, grouping by ability and accepting or encouraging children’s different “learning styles” are widely espoused but bad ideas. So too is the notion that pupils can discover complex ideas all by themselves. Teachers must impart knowledge and critical thinking.

Those who do so embody six aspects of great teaching, as identified by Mr Coe. The first and second concern their motives and how they get on with their peers. The third and fourth involve using time well, fostering good behaviour and high expectations. Most important, though, are the fifth and sixth aspects, high-quality instruction and so-called “pedagogical content knowledge”—a blend of subject knowledge and teaching craft. Its essence is defined by Charles Chew, one of Singapore’s “principal master teachers”, an elite group that guides the island’s schools: “I don’t teach physics; I teach my pupils how to learn physics.”

Branches of the learning tree

Teachers like Mr Chew ask probing questions of all students. They assign short writing tasks that get children thinking and allow teachers to check for progress. Their classes are planned—with a clear sense of the goal and how to reach it—and teacher-led but interactive. They anticipate errors, such as the tendency to mix up remainders and decimals. They space out and vary ways in which children practise things, cognitive science having shown that this aids long-term retention.

These techniques work. In a report published in February the OECD found a link between the use of such “cognitive activation” strategies and high test scores among its club of mostly rich countries. The use of memorisation or pupil-led learning was common among laggards. A recent study by David Reynolds compared maths teaching in Nanjing and Southampton, where he works. It found that in China, “whole-class interaction” was used 72% of the time, compared with only 24% in England. Earlier studies by James Stigler, a psychologist at UCLA, found that American classrooms rang to the sound of “what” questions. In Japan teachers asked more “why” and “how” questions that check students understand what they are learning.

But a better awareness of how to teach will not on its own lead to great teaching. According to Marie Hamer, the head of initial teacher training at Ark, a group of English schools: “Too often teachers are told what to improve, but not given clear guidance on how to make that change.” The new types of training used at Relay and elsewhere are intended to address that.

David Steiner of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, in Baltimore, characterises many of America’s teacher-training institutions as “sclerotic”. It can be easier to earn a teaching qualification than to make the grades American colleges require of their athletes. According to Mr Hattie none of Australia’s 450 education training programmes has ever had to prove its impact—nor has any ever had its accreditation removed. Some countries are much more selective. Winning acceptance to take an education degree in Finland is about as competitive as getting into MIT. But even in Finland, teachers are not typically to be found in the top third of graduates for numeracy or literacy skills.

In America and Britain training has been heavy on theory and light on classroom practice. Rod Lucero of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE), a body representing more than half of the country’s teacher-training providers, says that most courses have a classroom placement. But he concedes that it falls short of “clinical practice”. After finishing an undergraduate degree in education “I didn’t feel I was anywhere near ready,” says Jazmine Wheeler, now a first-year student at the Sposato Graduate School of Education, a college which grew out of the Match charter schools in Boston.

This fits with a pattern Mr Kane’s research reveals to be “almost constant”: new teachers lack classroom management and instruction skills. As a result they struggle at first before improving over the subsequent three to five years. The new teaching schools believe that those skills which teachers now pick up haphazardly can be systematically imparted in advance. “Surgeons start on cadavers, not on live patients,” Mr Kane notes.

“We have thought a lot about how to teach 22-year-olds,” says Scott McCue, who runs Sposato. He and his colleagues have crunched good teaching into a “taxonomy” of things to do and say. “Of the 5,000 or so things that go into amazing teaching,” says Orin Gutlerner, Sposato’s founding director, “we want to make sure you can do the most important 250.”

The curriculum of the new schools is influenced by people like Doug Lemov. A former English teacher and the founder of a school in Boston, Mr Lemov used test-score data to identify some of the best teachers in America. After visiting them and analysing videos of their classes to find out precisely what they did, he created a list of 62 techniques. Many involve the basics of getting pupils’ attention. “Threshold” has teachers meeting pupils at the door; “strong voice” explains that the most effective teachers stand still when talking, use a formal register, deploy an economy of language and do not finish their sentences until they have their classes’ full attention.

But most of Mr Lemov’s techniques are meant to increase the number of pupils in a class who are thinking and the amount of time that they do so. Techniques such as his “cold call” and “turn and talk”, where pupils have to explain their thoughts quickly to a peer, give the kinds of cognitive workouts common in classrooms in Shanghai and Singapore, which regularly top international comparisons.

Trainees at Sposato undertake residencies at Match schools. They spend 20 hours per week studying and practising, and 40-50 tutoring or assisting teachers. Mr Gutlerner says that the most powerful predictor of residents’ success is how well they respond to the feedback they get after classes.

This new approach resembles in some ways the more collective ethos seen in the best Asian schools. Few other professionals are so isolated in their work, or get so little feedback, as Western teachers. Today 40% of teachers in the OECD have never taught alongside another teacher, observed another or given feedback. Simon Burgess of the University of Bristol says teaching is still “a closed-door profession”, adding that teaching unions have made it hard for observers to take notes in classes. Pupils suffer as a result, says Pasi Sahlberg, a former senior official at Finland’s education department. He attributes much of his country’s success to Finnish teachers’ culture of collaboration.

As well as being isolated, teachers lack well defined ways of getting better. Mr Gutlerner points out that teaching, alone among the professions, asks the same of novices as of 20-year veterans. Much of what passes for “professional development” is woeful, as are the systems for assessing it. In 2011 a study in England found that only 1% of training courses enabled teachers to turn bad practice into good teaching. The story in America is similar. This is not for want of cash. The New Teacher Project, a group that helps cities recruit teachers, estimates that in some parts of America schools shell out about $18,000 per teacher per year on professional development, 4-15 times as much as is spent in other sectors.

As well as being isolated, teachers lack well defined ways of getting better. Mr Gutlerner points out that teaching, alone among the professions, asks the same of novices as of 20-year veterans. Much of what passes for “professional development” is woeful, as are the systems for assessing it. In 2011 a study in England found that only 1% of training courses enabled teachers to turn bad practice into good teaching. The story in America is similar. This is not for want of cash. The New Teacher Project, a group that helps cities recruit teachers, estimates that in some parts of America schools shell out about $18,000 per teacher per year on professional development, 4-15 times as much as is spent in other sectors.

The New Teacher Project suggests that after the burst of improvement at the start of their careers teachers rarely get a great deal better. This may, in part, be because they do not know they need to get better. Three out of five low-performing teachers in America think they are doing a great job. Overconfidence is common elsewhere: nine out of ten teachers in the OECD say they are well prepared. Teachers in England congratulate themselves on their use of cognitive-activation strategies, despite the fact that pupil surveys suggest they rely more on rote learning than teachers almost everywhere else.

It need not be this way. In a vast study published in March, Roland Fryer of Harvard University found that “managed professional development”, where teachers receive precise instruction together with specific, regular feedback under the mentorship of a lead teacher, had large positive effects. Matthew Kraft and John Papay, of Harvard and Brown universities, have found that teachers in the best quarter of schools ranked by their levels of support improved by 38% more over a decade than those in the lowest quarter.

Such environments are present in schools such as Match and North Star—and in areas such as Shanghai and Singapore. Getting the incentives right helps. In Shanghai teachers will not be promoted unless they can prove they are collaborative. Their mentors will not be promoted unless they can show that their student-teachers improve. It helps to have time. Teachers in Shanghai teach for only 10-12 hours a week, less than half the American average of 27 hours.

No dark sarcasm

In many countries the way to get ahead in a school is to move into management. Mr Fryer says that American school districts “pay people in inverse proportion to the value they add”. District superintendents make more money than teachers although their impact on pupils’ lives is less. Singapore has a separate career track for teachers, so that the best do not leave the classroom. Australia may soon follow suit.

The new models of teacher training that will start those careers have yet to be thoroughly evaluated. Early evidence is encouraging, however. Relay and Sposato both make their trainees’ graduation dependent on improved outcomes for students. A blind evaluation that Relay undertook of its teachers rated them as higher than average, especially in classroom management. At Ark, in England, recent graduates are seen by the schools that have hired them as among the best cohorts that they have received.

Mr Steiner notes, though, that it is not yet clear whether these new teachers are “school-proof”: effective in schools that lack the intense culture of feedback and practice of places like Match. This is a big caveat: across the OECD two-thirds of teachers believe their schools to be hostile to innovation.

If the new approaches can be made to work at scale, that should change. Relay will be in 12 cities by next academic year, training 2,000 teachers and 400 head teachers, including those from government-run schools. This year AACTE launched its own commission investigating ways in which its colleges could move to a similar model. In England Matthew Hood, an entrepreneurial assistant head teacher, has plans for a Relay-like “Institute for Advanced Teaching”.

This way, reformers hope, they can finally improve education on a large scale. Until now, the job of the teacher has been comparatively neglected, with all the focus on structural changes. But disruptions to school systems are irrelevant if they do not change how and what children learn. For that, what matters is what teachers do and think. The answer, after all, was in the classroom.

Written for and published on the UpWorThy ~ June 11, 2016.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml