The percentage of students at Washington, D.C., public schools who graduate from high school in four years is at an all-time high. But at 69 percent, the district’s graduation rate is well below the national average, which is north of 80 percent.

The percentage of students at Washington, D.C., public schools who graduate from high school in four years is at an all-time high. But at 69 percent, the district’s graduation rate is well below the national average, which is north of 80 percent.

So in a move that mirrors a broader national conversation about how to help kids who have more than a few obstacles in front of them succeed, the district this year put what it’s calling “pathway coordinators” into its schools to make sure kids at risk of dropping out get a diploma—and to help students who’ve gotten off track rebound.

Through a mixture of number-crunching, mentoring, and occasionally good-natured cajoling, these pathways coordinators track how students are doing and help those who are behind come up with plans for moving forward. Right now, the district has about 1,300 students it categorizes as overage and under-credited, meaning students who are under the age of 24 and more than two years behind. The ultimate goal is to get as many kids as possible through high school in four years and to help even those who need a little longer earn a diploma and move into either higher education or the workforce.

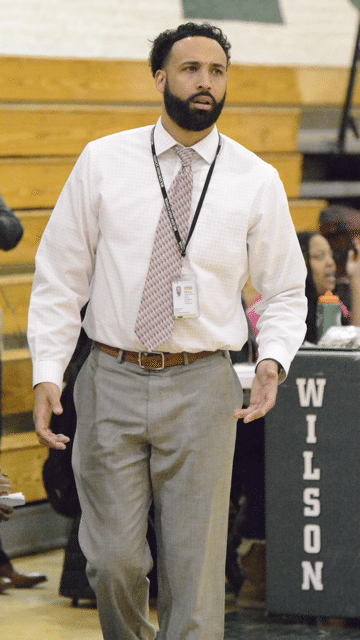

Angelo Hernandez—or “H,” as some of the kids call him—is the guy who oversees the pathways program at Wilson High School in a quiet part of the city five miles northwest of downtown. The school has the highest graduation rate—88 percent—of non-application schools in the city, but around 400 of the school’s 1,800 kids are under-credited—and around 85 of those students are both older than 18 and behind. Hernandez estimates that about 35 seniors need to make up at least three or four classes, meaning there’s plenty of work to do.

* * *

Hernandez, who’s been at the school for eight years but moved into the new role in August, knows a thing or two about struggling to get through high school. He was raised by a single mom in Philadelphia in a three-bedroom home that at various points housed as many as 10 people. He walked miles to school as a kid, and there was barely enough money for clothes sometimes; forget extracurricular activities. “It was very rough,” he recalled during an interview at his office. He was a popular athlete, but not always focused on studying, and it took him a couple extra months after his senior year technically ended to earn all the credits he needed to graduate. The day he picked up his diploma, his mom passed away. “Hearing it,” he said, “people say ‘How did you make it?’”

Hernandez “made it” with the help of coaches and teachers and a sheer unwillingness to give up, and now that experience puts him in a position to say to the kids who come through his office, “I was just like you,” he said. While his day-to-day job varies, he’s essentially the glue that keeps kids, teachers, and counselors connected and on the same page.

His mornings usually start with numbers—looking at the data teachers submit and figuring out which kids are failing a course or close to it and might need after-school classes to catch up, or going over attendance records to see who’s skipping school. Then comes the detective work. “The home life is really what I focus on,” Hernandez said. And he’s not above stopping by a student’s house to figure out what’s going on. Some kids don’t have enough to eat, or even someplace to sleep. Others are taking care of younger brothers and sisters, or working after school to help pay the bills. Many don’t have high hopes for what school has to offer. “They felt like they weren’t getting any attention,” he said.

“Once they see you’re invested, they start to be invested, too.”

Lauren Caldwell is a senior at Wilson who can frequently be found hanging out in Hernandez’s office. The two met when she was a freshman and he was working as the school’s ninth-grade dean, basically the person in charge of disciplining freshmen. Now, Caldwell manages the basketball team, which he coaches. While she generally likes her classes and teachers, Caldwell isn’t convinced that all of her instructors really care about their students’ lives. But Hernandez, who busied himself with something in the hall while we talked in his office, is different. “He’s not judging me,” she said, adding that “H” is a good listener and that she can tell he’s not out to hurt her, even when they disagree on something.

Angelo Hernandez (Courtesy of Angelo Hernandez)

Brianae Barkley, Caldwell’s friend, agrees. “A lot of people feel like teachers don’t help them or they’re not for them,” she said. And it “seems fake” when teachers act like they care in class but then don’t say hello in the halls, she added. But she knows Hernandez cares about her. After a fight with a teacher when she was a freshman, Hernandez paid her a visit at track practice, where they talked and “got closer.” When she fell behind in science, he worked with her on a plan to catch up. “The consistency thing is key,” Hernandez said later. “Once they see you’re invested, they start to be invested, too.”

Barkley is one of the students who signed up for “Tenacity and Employability,” a class Hernandez teaches where students learn how to deposit checks, how to dress for interviews, even how to “code switch.” While those are skills that many kids from wealthy families learn at home, Hernandez said that lots of his students haven’t had a chance to see them modeled anywhere. “They watch everything we do,” Hernandez, who has a 15-year-old and a one-year-old of his own, said.

The focus on such topics is a symbol of a shift in how schools view their responsibility to educate students. Most of the nation’s public-school students are now low-income, and schools are increasingly being asked to help students find food, clothing, and even housing, in addition to covering typical academic subjects. Most public-school students are also now children of color, while around 80 percent of teachers are white, which has raised questions about racial bias and disparities in everything from school discipline to grading.

William Haith is the man who recommended Hernandez for the pathways job. He’d been his supervisor and saw, he said during an interview at his office, that “he was adamant about being resourceful for students.” And anyway, Haith said, Hernandez had in some ways been doing the job unofficially for years—and filling a real void, one with which Haith is personally familiar.

Haith is now an assistant principal for the ninth grade at Wilson. But nearly two decades ago, he graduated from the school as a student. Things, he said during an interview in his office, were a little different back then. There are more counselors now, and the adults in the building are paying more attention to the social-emotional health of the kids who walk through the doors. Of course there have always been students living in violent neighborhoods or growing up in poverty or children who are the first in their families to make it through high school. But there’s more awareness now, he said.

Tennille Bowser, an assistant principal who’s been at the school a decade, sees that, too. The pathways position is still new, so it’s unclear exactly how much will change as a result. But anytime there’s more attention being paid to kids at risk of falling behind, that’s positive, she said. “They kind of put their money where their mouth is,” she added, which is especially crucial now that schools are being expected to help kids with more than just academics, but also with things like finding a place to sleep.

“It’s very delicate work and not everybody can do it.”

Beyond the act of formalizing Hernandez’s role, another reason at-risk students are receiving more attention now is simply that teachers and administrators have better access to data, so it’s harder for kids to slip behind unnoticed. Where schools might have had time to look at each kid’s performance once a semester a decade ago, now, teachers can put attendance records, test scores, and homework grades into a database that Hernandez can track regularly, using a color-coding scheme to identify kids who are doing well and kids who aren’t. If a kid isn’t at school, Hernandez can go to his house and figure out why and how to help. If a kid only needs to make up a bit of work, he can help the student enroll in after-school makeup classes. If a kid needs more than that, he can talk to her about courses she can take either online or in-person. He can urge a kid to enroll in summer school to make up lost ground before the next year.

Washington, D.C., added pathways coordinators to its high schools to try to help kids who are behind on credits catch up.

And crucially, he can look at the numbers to predict where things are about to go wrong and try to prevent that from happening, working with counselors to develop plans for each student. Last school year, about 250 kids at the school needed to make up credits outside of the regular school day, he said. During the first semester of this school year, though, only 35 students needed to do that. That’s partially because the school added an extra class to the day, so students can make up a class during the regular school schedule. But it’s also because Hernandez has been combing through data to catch kids before they fall too far behind.

“It’s very delicate work and not everybody can do it,” Hernandez said. He tries not to talk at kids but rather to spend the bulk of his time listening. Kids who come from stable homes and financial means have the luxury of thinking about how they’re going to take over the world. The kids he works with are thinking about how they’re going to find clean clothes for school or how they’re going to get there at all, he said.

So Hernandez spends some of his time helping kids think about longer-term possibilities, like college or a job. Most of the kids he works with go to community college or a trade school, he said, while some head straight into the workforce. No matter where they go, Hernandez tries to show his students that the world is bigger than their high-school existence and that they can play a positive, active role in shaping it.

* * *

The economic impact is part of why the district says it’s investing in pathway coordinators. Kids who simply drop out don’t just disappear; they grow into adults who aren’t equipped with the skills to take advantage of an economy that increasingly values those who are educated. So the district has put pathways coordinators into its high schools in part to help plot the transition to whatever is next. Separately, the district’s alternative schools, for students who are coming back to school after a time away or who need a flexible schedule, set up college visits so students can see someone who looks like them pursuing higher education.

That’s become more pressing in recent years, particularly at Wilson. In the 1950s, almost all of the students were white. A few decades later, it had shifted to mostly students of color. Today, the school pulls some students (often wealthier and white) from the neighborhood around it, and others, often students of color, commute in from lower-income parts of the city. And while the school boasts a relatively high graduation rate of around 88 percent, up about 10 points from the 2014-15 year, standardized tests scores have declined, in part because of pushback to testing from students and their families.

“We can only help when we can get to the root cause,” Haith said. Like Hernandez, he understands on a personal level the challenges some of his students face beyond just how a quadratic equation works, and how students don’t always feel empowered by the teachers who are supposed to believe in their ability to succeed. Haith, who is black, grew up in a high-poverty part of Washington and has vivid memories of not feeling welcome in an advanced-placement class as a student, whether because of his skin color or where he came from or the fact that he was a football player. “That was detrimental and I still remember it to this day,” he said.

“We’re in tune with what they’re going through,” Hernandez said, adding that he sees his job partially as a way to take on some of the work traditionally done by assistant principals like Haith, but in a way that gives him time to focus on the kids who most need help. “We spend a lot of time on students who have everything,” he lamented. But “I think we’re moving in the right direction.”

Andrew Barnes, the 12th grade dean agrees. The culture has changed in the last couple of years, he said, since the school brought in a new principal, Kimberly Martin, who came to Washington from Aspen, Colorado. And it’s not that anyone was trying to ignore at-risk kids before, but the creation of the pathways position frees up overworked counselors and creates a go-to person when it comes to guiding kids who are behind in credits.

Helping more students on the path to graduation doesn’t always require big moves. “The small things work so much for these kids,” Hernandez said. Saying good morning to a kid can matter, something Barkley alluded to. It’s hard to say how much of a difference pathway coordinators are making at the district’s schools.

They’re just one person tackling a complex issue, and the district’s graduation rate, despite improvements in recent years, has been persistently low. But Hernandez doesn’t think there’s anything bad about investing in a person who can sift through data and use his findings to help kids who are struggling earn a diploma. “When a kid wants to communicate with you,” he said, “that means you’re doing something right.”

Written by Emily Deruy for The Atlantic ~ February 14, 2017.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml