“When he fell, civil authority was trampled underfoot.”

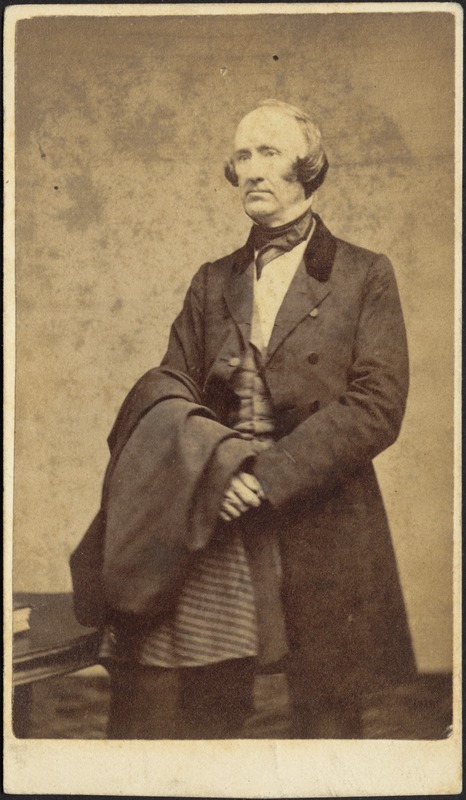

Wendell Phillips

BOSTON, Mass., Dec. 8, 1837 – A 26-year-old man, with oratorical powers far beyond his age, tonight soared nearer to leadership of the Abolitionist movement, with a stirring speech on the recent murder of Elijah Lovejoy which held spellbound an audience that filled Faneuil Hall.

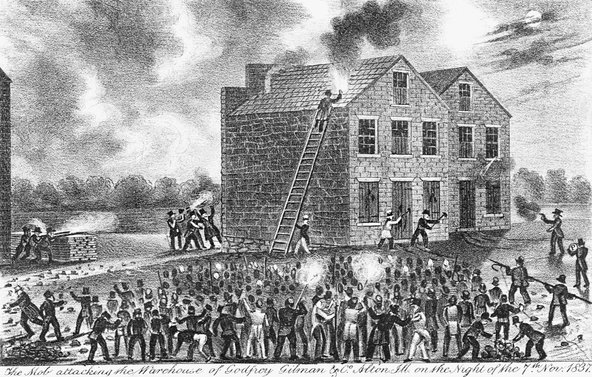

The speaker was Wendell Phillips. His subject was the crusading editor who was murdered by a mob at Alton, Illinois, on November 7. Lovejoy, who had been driven from city to city by opponents of his Abolitionist crusade in the West, had suffered the destruction of three newspaper presses. Finally, arming himself with the consent of the authorities, he resisted what was to be the final attack upon him.

The point that particularly aroused Mr. Phillips, as it has a wide section of opinion throughout the North, is that pro-slavery spokesmen, including at least one clergyman, have blamed Lovejoy as responsible for his own death by persistence in acting contrary to public opinion, comparing the mob that killed him to the participants in the Boston Tea Party.

Elijah Lovejoy was not only defending the freedom of the press, but he was under his own roof, in arms with the sanction of civil authority. The men who assailed him went against and over the laws. The mob, as the gentleman terms it – mob, forsooth; certainly we sons of the tea-spillers are a marvelously patient generation; – the “orderly mob” which assembled in the Old South to destroy the tea, were met to resist, not the laws, but illegal enactions. Shame on the American who calls the tea tax and stamp tax laws.

Elijah P. Lovejoy

Our fathers resisted, not the King’s prerogative, but the King’s usurpation. To find any other account you must read our Revolutionary history upside down. Our state archives are loaded with arguments of John Adams to prove the taxes laid by the British Parliament unconstitutional-beyond its powers. It was not until this was made out that the men of New England rushed to arms. The arguments of the Council Chamber and the House of Representatives preceded and sanctioned the contest. To draw the conduct of our ancestors into a precedent for mobs, for a right to resist laws we ourselves have enacted, is an insult to their memory.

The difference between the excitements of those days and our own, which the gentleman in kindness to the latter has overlooked, is simply this: the men of that day went for the right, as secured by the laws. They were the people rising to sustain the laws and Constitution of the province. The rioters of our day go for their own wills, right or wrong.

Sir, when I heard the gentleman lay down principles which place the murderers of Alton side by side with Otis and Hancock, with Quincy and Adams, I thought those pictured lips (pointing to portraits in the hall), would have broken into voice to rebuke the recreant American – the slanderer of the dead. The gentleman said he should shrink into insignificance if he dared to gainsay the principles of these resolutions. Sir, for the sentiments he has uttered, on soil consecrated by the prayers of Puritans and the blood of patriots, the earth should have yawned and swallowed him up.

Some persons seem to imagine that anarchy existed at Alton from the commencement of these disputes. Not at all. “No one of us,” says an eyewitness and a comrade of Lovejoy, “has taken up arms during these disturbances but at the command of the mayor.” Anarchy did not settle down on that devoted city till Lovejoy breathed his last. Till then the law, represented in his person, sustained itself against its foes. When he fell, civil authority was trampled underfoot. He had planted himself on his constitutional rights, appealed to the laws, claimed the protection of civil authority, taken refuge under the broad shield of the Constitution; when through that he was pierced and fell, he fell but one sufferer in a common catastrophe: He took refuge under the banner of liberty-amid its folds; and when he fell, its glorious stars and stripes, the emblem of free institutions, around which cluster so many heart-stirring memories, were blotted out in the martyr’s blood.

It has been stated, perhaps inadvertently, that Lovejoy or his comrades fired first. This is denied by those who have the best means of knowing. Guns were first fired by the mob. After being twice fired on, those within the building consulted together and deliberately returned the fire. But suppose they did fire first. They had a right to do so; not only the right, which every citizen has to defend himself, but the further right which every civil officer has to resist violence. Even if Lovejoy fired the first gun, it would not lessen our claim to his sympathy, or destroy his title to be considered a martyr in defense of a free press. The question now is, Did he act within the Constitution and the laws?

Throughout that terrible night I find nothing to regret but this, that, within the limits of our country, civil authority should have been so prostrate as to oblige a citizen to arm in his own defense, and to arm in vain.

Godfrey and Gilman warehouse, November 7, 1837

Mr. Chairman, from the bottom of my heart I thank that brave little band in Alton for resisting. We must remember that Lovejoy had fled from city to city – suffered the destruction of three presses patiently. At length he took counsel with friends, men of character, of tried integrity, of wide views, of Christian principle. They thought the crisis had come; it was full time to assert the laws. They saw around them, not a community like our own, of fixed habits, of character molded and settled, but one “in the gristle, not yet hardened into the bone of manhood.” The people there, children of our older States, seem to have forgotten the blood-tried principles of their fathers the moment they lost sight of their New England hills. Something was to be done to show them the priceless value of the freedom of the press, to bring back and set right their wandering and confused ideas. He and his advisers looked out on a community, staggering like a drunken man, indifferent to their right and confused in their feelings. Deaf to argument, happily they might be stunned into sobriety. They saw that of which we cannot judge-the necessity of resistance. Insulted law called for it. Public opinion, fast hastening on the downward course, must be arrested.

Does not the event show they judged rightly? Absorbed in a thousand trifles, how has the nation all at once come to a stand? Men begin, as in 1776 and 1640, to discuss principles, to weigh characters, to find out where they are. Happily, we may awake before we are borne over the precipice.