“The states can never lose their powers until the whole people of the United States are robbed of their liberties.”

Poughkeepsie, New York, 1787 – The youngest of the vital young men who hammered into form the Federal Constitution derided the fears of conservative New Yorkers that establishment of the national government would mean the extinction of State sovereignty – a fear so strong among the older New York hierarchy that it still threatened older New York ratification of the Constitution.

Poughkeepsie, New York, 1787 – The youngest of the vital young men who hammered into form the Federal Constitution derided the fears of conservative New Yorkers that establishment of the national government would mean the extinction of State sovereignty – a fear so strong among the older New York hierarchy that it still threatened older New York ratification of the Constitution.

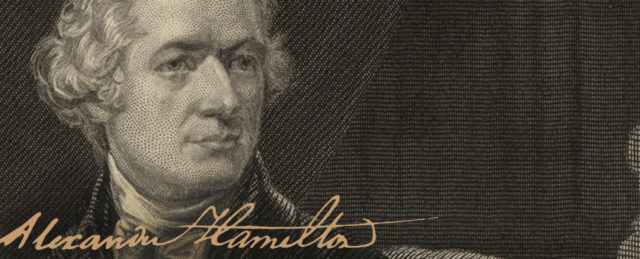

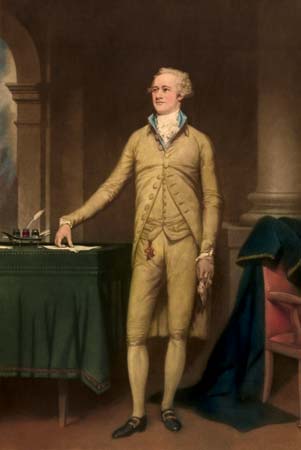

Alexander Hamilton, alien born in the Barbadoes, and this year only 30 years old, drew his bow in a personal contest of debate with Governor George Clinton at the New York Constitutional Convention called to meet under Governor Clinton’s chairmanship. The site itself is significant – this city settled exactly 100 years ago, unofficial center of the up-river patroons and far removed from the more cosmopolitan environs of New York City.

The stage already has been set for this debate through an exchange of letters published in the New York Journal. Governor Clinton is well known as the author signing himself “Cato,” opposing ratification, and Hamilton as the writer of the “Caesar” replies. Here Hamilton must make up in legal and oratorical skill Governor Clinton’s advantage of 18 years of seniority and political experience. However, on his side in debate are the month-in and month-out sessions with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in drafting this experimental Constitution, and long forays into arguments embodied in articles in the Federalist.

It was the consensus here that Mr. Hamilton had delivered one of his greatest speeches, lifting the foundation he undoubtedly is building for great future influence and reputation. Among his auditors were those who applauded him, not the least being his own coterie of up-river friends who have been enchanted by him since this dashing young soldier and lawyer married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of General Schuyler and an aristocrat.

But results are what count, in politics as in battles, and at this point it is by no means certain that Mr. Hamilton has carried the field. The State Convention will not be stampeded into action, and delay now is the same as an adverse vote.

Gentlemen indulge too many unreasonable apprehensions of danger to the state governments; they seem to suppose that the moment you put men into a national council they become corrupt and tyrannical, and lose all their affection for their fellow citizens. …

The state governments are essentially necessary to the form and spirit of the general system. As long, therefore, as Congress has a full conviction of this necessity, they must, even upon principles purely national, have as firm an attachment to the one as to the other. This conviction can never leave them, unless they become madmen. While the Constitution continues to be read and its principle known, the states must, by every rational man, be considered as essential, component parts of the Union; and therefore the idea of sacrificing the former to the latter is wholly inadmissible.

The objectors do not advert to the natural strength and resources of state governments, which will ever give them an important superiority over the general government. If we compare the nature of their different powers, or the means of popular influence which each possesses, we shall find the advantage entirely on the side of the states. This consideration, important ~ as it is, seems to have been little attended to. The aggregate number of representatives throughout the states may be two thousand. Their personal influence will, therefore, be proportionably more extensive than that of one or two hundred men in Congress. The state establishments of civil and, military officers of every description, infinitely surpassing in number any possible correspondent establishments in the general government, will create such an extent and complication of attachments as will ever secure the predilection and support of the people. Whenever, therefore, Congress shall meditate any infringement of the state constitutions, the great body of the people will naturally take part with their domestic representatives. Can the general government withstand such a united opposition? Will the people suffer themselves to be stripped of their privileges? Will they suffer their legislatures to be reduced to a shadow and a name? The idea is shocking to common sense. From the circumstances already explained, and many others which might be mentioned, results a complicated, irresistible check, which must ever support the existence and importance of the state governments. The danger, if any exists, flows from an opposite source. The probable evil is, that the general government will be too dependent on the state legislatures, too much governed by their prejudices, and too obsequious to their humors; that the states, with every power in their hands, will make encroachments on the national authority, till the Union is weakened and dissolved.

There are certain social principles in human nature from which we may draw the most solid conclusions with respect to the conduct of individuals and of communities. We love our families more than our neighbors; we love our neighbors more than our countrymen in general. The human affections, like the solar heat, lose their intensity as they depart from the center, and become languid in proportion to the expansion of the circle on which they act. On these principles, the attachment of the individual will be first and forever secured by the state governments; they will be a mutual protection and support. Another source of influence, which has already been pointed out, is the various official connections in the states. Gentlemen endeavor to evade the force of this by saying that these offices will be in- significant. This is by no means true. The state officers will ever be important, because they are necessary and useful. Their powers are such as are extremely interesting to the people; such as affect their property, their liberty, and life.

What is more important than the administration of justice and the execution of the civil and criminal laws? Can the state governments become insignificant while they have the power of raising money independently and without control? If they are really useful, if they are calculated to promote the essential interests of the people, they must have their confidence and support. The states can never lose their powers till the whole people of America are robbed of their liberties. These must go together; they must support each other, or meet one common fate . . .

With regard to the jurisdiction of the two governments, I shall certainly admit that the Constitution ought to be so formed as not to prevent the states from providing for their own existence; and I maintain that it is so formed, and that their power of providing for themselves is sufficiently established . . .

That two supreme powers cannot act together is false. They are inconsistent only when they are aimed at each other or at one indivisible object. The laws of the United States are supreme as to all their proper, constitutional objects; the laws of the states are supreme in the same way. These supreme laws may act on different objects without clashing; or they may operate on different parts of the same common object with perfect harmony. Suppose both governments should lay a tax of a penny on a certain article; has not each an independent and uncontrollable power to collect its own tax? The meaning of the maxim, there cannot be two supremes, is simply this – two powers cannot be supreme over each other . . .

Sir, we cannot reason from probabilities alone. When we leave common sense, and give ourselves up to conjecture, there can be no certainty, no security in our reasonings.

~ Postlogue ~

~ Postlogue ~

Without ratification of the Constitution by New York, it is doubtful if there ever could have been a Federal Government. A loose confederation of states – as Jefferson, Madison and Hamilton and the major statesmen who had joined in the Constitutional Convention well knew – could never be a power in the world. It would more likely become, like the Germanic states, a breeding ground for internecine wars.

New York as a state was ambitious. It was wealthy. Trade was making New York the shipping and financial center of the New World, at a time when soil depletion already was robbing the South of its earlier massive wealth built on cultivation of cotton and tobacco. In New York, Governor Clinton exerted a leadership that carried him seven times into the Governorship. New York felt that already it was a power on its own, bigger in many ways than the Federal establishment to which it was asked to delegate so much.

Had not the state by its own resources made its economy great, despite occupation of the city by the British throughout the Revolution? Had it not settled its own Indian wars in the western reaches with its own resources? Had not Governor Clinton personally led the fight that already had established New York’s expansionist claims to the so-called New Hampshire grants, later to become the State of Vermont?

No, Hamilton, unlike Patrick Henry, had not found in this State Convention his moment to sweep up a victory with words. Rather, he must content himself with stimulating anew men’s thoughts.

Ratification of the Constitution by New York must wait another year, until a majority of the other states had acted favorably.

As for Hamilton, he wasted no time in moping. Already he was preoccupied with plans to run the Federal Government on a sound business system; it was inevitable that he would add to his legal stature great political honors – the Secretaryship of the Treasury, establishment of New York’s first chartered bank. It was equally inevitable in the hard, competitive society in which he chose to become a harsh competitive individual that he would make enemies. But as yet his path, that led almost to the Presidency itself, had not yet been permanently halted by Aaron Burr.

Even in a country as small as the United States of 1787, there was room for vast contrasts, such as those marking the difference between Hamilton’s adopted northern career and the softer but sturdy accents of Virginia, where James Madison was nominated by his seniors to present the case for the Federal Constitution to the Virginia Constitutional Assembly.