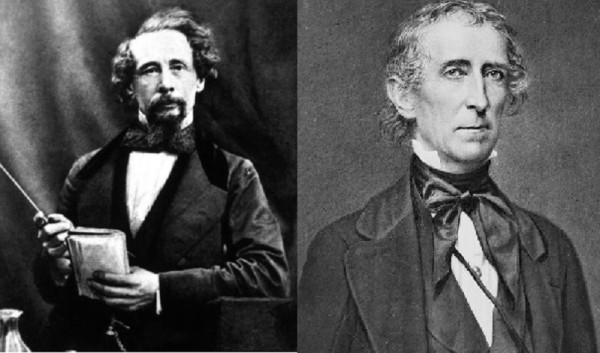

Charles Dickens and President John Tyler

As part of an extensive tour of the United States that encompassed most of the first half of 1842, English author Charles Dickens earned an invitation to meet President John Tyler at the White House. However, this visit left a lot to be desired on the part of the author, beginning with his attempt to actually locate the commander in chief.

As explained in his travelogue American Notes, Dickens and an unnamed official, “having twice or thrice rung a bell which nobody answered,” simply entered the White House and attempted to find the president on their own.

After wandering upstairs and catching the attention of a servant, Dickens noticed how the others gathered in a waiting room had no compunction about spitting tobacco juice as they pleased. He wrote, “Indeed all these gentlemen were so very persevering and energetic in this latter particular, and bestowed their favours so abundantly upon the carpet, that I take it for granted the Presidential housemaids have high wages.” While he didn’t have to wait long to see President Tyler, the meeting soon unfolded into an awkward spectacle.

Tyler commented on the youthful appearance of the 30-year-old writer, who failed to reply in kind to the “worn and anxious” 51-year-old president. The two then sat in silence near a hot stove until Dickens excused himself, sarcastically noting that his host was clearly very busy.

The disappointing visit to the Executive Mansion was a microcosm of Dickens’ overall experience in the United States. Overwhelmed by the mobs of people who gathered to see him, dismayed by the ongoing institution of slavery, and frustrated by his inability to generate interest in international copyright laws, the author vented his criticisms of the titular country when American Notes was published later that year, in turn igniting the ire of U.S. citizens until Dickens returned to make amends in 1867.

Visitors enjoyed near-unfettered access to the White House for most of the 19th century.

While the concept of someone breezing into the White House seems unusual in this day and age, it was actually pretty common for several decades before and after Dickens’ visit.

The practice began with the mansion’s second resident, Thomas Jefferson, who encouraged visitors to the building by displaying artifacts from the Lewis and Clark Expedition and even placing taxidermied bears on the lawn. While James Monroe installed gates around the premises, visitors could still largely enter the building as they wished, except for mornings or when the president was out of town. The near-unfettered access was first curtailed in the mid-1890s, when First Lady Frances Cleveland ordered the gates locked over safety concerns for her young daughter, Ruth. Although Warren G. Harding reopened the grounds to the public in the early 1920s, the arrival of World War II brought stricter security measures that all but closed off the “People’s House” to the people, save for those with previously approved appointments.

Written and Published on History Facts ~ December 16, 2024