“The negro vote was not at all committed to Kennedy, but it went there because Mr. Nixon did not do anything to win it. I understand his view but felt he was making a mistake …”

The famous retired baseball star – at that time an NAACP fundraiser and vice president of Chock Full O’ Nuts coffee – campaigned hard for Richard Nixon in 1960. Here, in the aftermath of defeat, he offers suggestions as to how the party of Lincoln might attract more future African-American voters in his (and Nixon’s) native California.

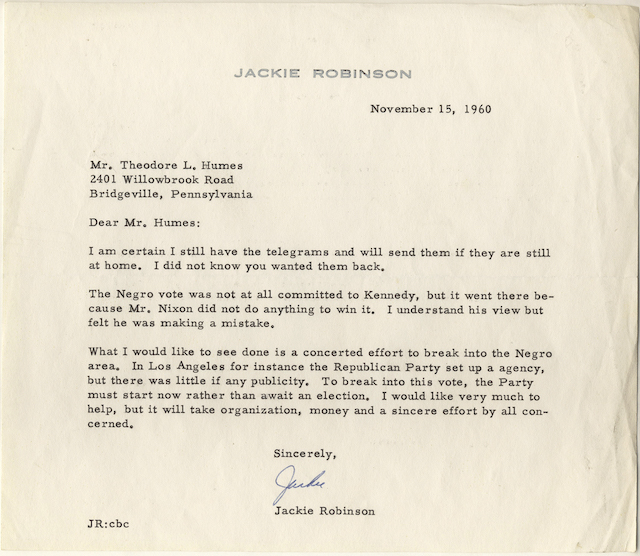

JACKIE ROBINSON. Typed Letter Signed, “Jackie”, to Theodore L. Humes. [n.p.], November 15, 1960. 1 p., on personal letterhead.

Partial Transcript

“The negro vote was not at all committed to Kennedy, but it went there because Mr. Nixon did not do anything to win it. I understand his view but felt he was making a mistake. … What I would like to see done is a concerted effort to break into the Negro area. In Los Angeles for instance the Republican Party set up a agency, but there was little if any publicity. To break into this vote, the Party must start now rather than await an election. I would like very much to help, but it will take organization, money and a sincere effort by all concerned …”

Historical Background

After retiring from Major League Baseball in 1957, Robinson wrote a news column, hosted a radio program, and served as vice president of Chock Full O’ Nuts coffee. He also became vitally interested in politics at a great turning point in American history. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the civil rights movement reached its apex, and African-Americans were shifting their allegiance from the Republican to the Democratic Party. Robinson worked with the NAACP, and joined A. Philip Randolph in leading a student march on Washington in 1958.

Robinson sought to influence both party’s nomination battles in 1960 by drawing attention to each candidate’s record on civil rights issues. He favored Hubert Humphrey among the Democratic hopefuls, and Vice President Richard Nixon for the Republicans. Robinson did not like John F. Kennedy because of his role in defeating the 1957 Civil Rights Bill in the Senate, and because Kennedy did not look him in the eye at their initial meeting, admitting his ignorance of “the Negro.” When Kennedy beat out Humphrey and others to win the nomination, and chose Lyndon Johnson of Texas (then perceived as a segregationist) as his running mate, Robinson turned to back Nixon.

Robinson was harshly criticized in some circles for his support for Nixon. When Chock Full O’ Nuts President William Black refused to permit the unionization of his company, the AFL-CIO refused a request from the NAACP for $50,000 for a black voter registration drive. Many in New York’s black community turned against the old hero.

Nixon himself disappointed Robinson in the closing stages of the campaign, neglecting to make an appearance in Harlem. His campaign managers leaned on Robinson’s celebrity, and were unwilling to devote time and energy to the African-American vote. The most consequential break came when a judge in Georgia sentenced Martin Luther King, Jr. to four months in prison for his role in a sit-in. According to biographer Arnold Rampersad:

At the almost frantic urging of Harry Belafonte, now a member of King’s inner circle, Jack appealed to Nixon campaign leaders for a direct show of support for the civil rights leader. William Safire, an admirer of Robinson . . . remembered him arguing vehemently at the midwestern hotel where they were staying that Nixon had to intervene. ‘He has to call Martin right now, today,’ Robinson pleaded with Safire. . . . Safire took Robinson to see Robert Finch, who was managing Nixon’s campaign. Finch, in turn, escorted Robinson into a meeting with the candidate himself. Ten minutes later, Robinson returned to Safire, ‘tears of frustration in his eyes.’ ‘He thinks calling Martin would be ‘grandstanding,’’ Jack blurted out. ‘Nixon doesn’t deserve to win.’

Instead, it was John F. Kennedy who placed the call to Coretta Scott King, while Bobby Kennedy pressured the Georgia judge to shorten King’s sentence. As Rampersad concludes, “The black vote, undecided until then, swung heavily to Kennedy, especially after King’s father, a powerful pastor in Atlanta, openly threw his support behind the Senator. In at least three states that Kennedy carried narrowly (including Illinois, which he won by only nine thousand votes), the overwhelming support of black voters obviously made the difference.”

Nixon lost the election and warmly thanked Robinson for his efforts, which were true to the end despite the confrontation over the call to the Kings. It led him to write letters like this, an astute analysis of what the Republican Party needed to do to regain the allegiance of African-American voters, who had long inclined toward the party of Lincoln.

Robinson continued to work with moderate, pro-civil rights Republicans, especially New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, but came to respect the contributions of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson to the advancement of racial equality. In 1968, Robinson turned against Nixon, arguing that his unlikely alliance with Southern segregationist Strom Thurmond, and his naming of Spiro Agnew as his vice presidential candidate, indicated that he had “sold out” and “really prostituted himself to get the Southern vote.” Indeed, Nixon’s narrow victory over Humphrey in the 1968 election marked the beginning of the Republican Party’s “Southern strategy,” the flip side of which was continued neglect of the African-American vote. To this day, in a general sense, Republicans continue to run strongest in the South, and African-Americans predominantly vote Democratic.

Jackie Robinson, 2007 by Jerry Blank

Jack Roosevelt “Jackie” Robinson (1919-1972) was the first African-American major league baseball player of the modern era, whose debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers ended eighty years of segregation in baseball and helped inspire the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Robinson was born into a family of Georgia sharecroppers in 1919, and moved to Pasadena, California, where he was raised by his mother. Though at first attracted to gang life, he starred in baseball, football, tennis, and track and field. He attended Pasadena Junior College and U.C.L.A., where he was the first athlete at that school to letter in four sports. In 1942, Robinson was drafted, and served in the 761st “Black Panthers” Tank Battalion, but was arrested for insubordination after refusing to move to the back of a bus. He was honorably discharged and joined the Negro Baseball League Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. While there, he was scouted by Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, who offered Robinson a contract with the Dodgers. Robinson played for their minor league Montreal club in 1946, and made his Major League debut on April 15, 1947, enduring great harassment from fans and players of opposing teams during his first year. With great dignity and restraint, Robinson played through it, and became the lynchpin of one of the great teams in baseball history. Robinson helped Brooklyn win its first World Series title in 1955, was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, and was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

References

Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York, 1997), 340-359, 424- 431.

Written for and published by Seth Kaller, Inc., Historic Documents