The curriculum in today’s public schools leaves much to be desired.

But have you ever noticed how difficult it is to figure out exactly what kind of books our children are reading in school?

But have you ever noticed how difficult it is to figure out exactly what kind of books our children are reading in school?

Because of that common difficulty, it felt like winning the lottery when I was able to track down a K-5 reading list list from EL Education, the newly approved English Language Arts curriculum for Minnesota public schools.

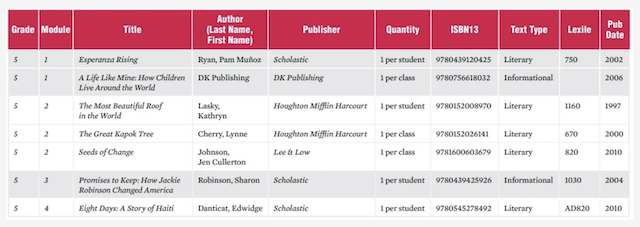

Here’s a look at their recommended reading list for 5th grade:

A few observations are in order.

For starters, consider how short some of these books are:

* Eight Days: A Story of Haiti clocks in at 32 pages;

* Seeds of Change comes in at 40;

* The Great Kapok Tree also comes in at 40

All three have bright, colorful pictures and fairly limited text on each page, something that’s certainly fine, but less than what I would expect a 5th-grader could handle reading.

It seems my instinct is not off in this, for looking at the description pages for each of these titles on Barnes and Noble, the age range for each was categorized as 4-7 years, 6-11 years, and 4-8 years respectively.

I also couldn’t help but notice how politically correct themes seemed to permeate this reading list. Three of the titles focus on environmental issues, while other titles appear to place a heavy emphasis on diversity and multicultural issues.

It’s further interesting to note that most of these titles tend to run in the non-fiction category. Many of us would likely consider that a good thing. But given the recent article in the Atlantic noting how students don’t read full books any more, and when they do, they’re often assigned more informational texts like these—much to their long-term detriment—I’m wondering if we should rethink that mindset.

I am also rethinking that theory based on the following statement from a Minnesota teacher and curriculum manual for elementary grades from 1916:

In teaching upper-grade pupils ‘how to study,’ text-books will sometimes serve as reading material, but literature will, in the main, be the subject-matter used by all pupils in learning to read. Therefore it will not be handled as for literary interpretation, will not be analyzed in that way, but will be read for reading’s sake, – selected because there is positive proof that pure literature makes the best subject-matter for use in studying the art of reading. [Emphasis added.]

Given this statement, it’s interesting to see what reading materials were suggested for 5th-graders in the state way back in 1916. Here’s what the manual said:

[The 5th-grade student] likes to hear read or told the Arthurian legends, tales of Ulysses (especially when recognized as an allegory), Beowulf, Roland, etc., the story of Perseus and Medea, tales of local and state history, and of historical characters everywhere in the United States. He also likes Ernest Thompson Seton’s stories, as well as books like Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’ and Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island,’ though these are too difficult for class use in the oral reading hour.

Beyond the specific titles listed in the paragraph above, a companion guide — the Minnesota School Library List — mentioned repeatedly as an important supplemental source in the manual, offers some insight into what these books might include:

* “Arthurian legends” – King Arthur and his Knights, by Radford;

* “The story of Perseus and Medea” – Famous men of Greece, by Haaren and Poland;

* “Tales of local and state history, and of historical characters everywhere in the United States” – Abraham Lincoln, by Baldwin; American Book of Golden Deeds, by Baldwin; True story of Christopher Columbus, by Brooks; True story of George Washington, by Brooks; First Book in American History, by Eggleston; Four American Pioneers, by Perry

Now compare this list with the one used today from EL Education. These books are far longer, give a far broader historical context, and also present many more examples of noble character and true heroism than those used in today’s 5th-grade classrooms.

And consider some of the individual reading assignments advanced by the 1916 curriculum manual, such as those written by Poe and Stevenson. I’ve read both The Gold Bug and Treasure Island as an adult, and from what I recall, neither work was a walk in the park reading-wise. Both were assuredly intriguing tales, but both also required a high level of focus given the demanding vocabulary, sentence structure, and plot lines each employed.

Clearly the 5th-graders of 1916 could handle these works… so why is the curriculum in today’s schools expecting so little of students in the same grade?

Why does all this matter?

It matters because there are still schools out there that require their 5th-grade students to read challenging texts – whole books, not excerpts that are nothing more than the CliffsNotes-version of a famous work. There are still schools that offer a curriculum which gives a broader historical context, rather than one which simply spews the latest politically correct talking points.

Unfortunately, the institutions that offer such curriculum are not our local public schools. They’re the private schools, microschools, or homeschools that not every family can afford. As such, many of our children are relegated to schools which teach to the lowest common denominator, never giving students the chance to learn, think, and climb higher than expected on the ladder of academic ability.

And this is exactly why so many families – 75% of school parents in Minnesota – from both sides of the political aisle want to see school choice and Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) implemented in our state.

Families want the chance – particularly the financial resources – to choose a school that offers a demanding curriculum that encourages students to aim high academically. They also want their local public schools to experience some competition in order to encourage them on to a higher standard.

Isn’t it time we give our families that opportunity with school choice and Education Savings Accounts?

October 25, 2024

~ The Author ~

Annie Holmquist is a cultural commentator hailing from America’s heartland who loves classic books, architecture, music, and values. Annie was a longtime contributor to Intellectual Takeout.

Annie Holmquist is a cultural commentator hailing from America’s heartland who loves classic books, architecture, music, and values. Annie was a longtime contributor to Intellectual Takeout.

Annie received a B.A. in Biblical Studies from the University of Northwestern-St. Paul. She also brings 20+ years of experience as a music educator and a volunteer teacher – particularly with inner city children – to the table in her research and writing and is a cultural commentator hailing from America’s heartland who loves classic books, architecture, music, and values.