In 1933, a group on businessmen conspired to unseat President Roosevelt and overthrow the government. One man stopped them…

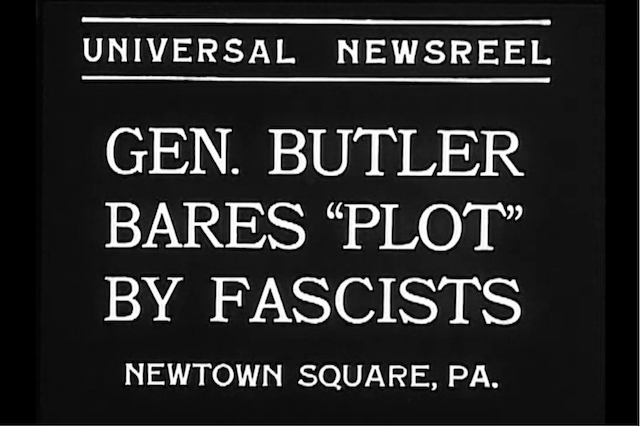

Still from Universal newsreel footage of Smedley Butler describing his 1934 congressional committee testimony (Wikimedia Commons)

Toward the climax of director and screenwriter David O. Russell’s new historical drama Amsterdam (2022), Dr. Burt Berendsen (Christian Bale) narrates a line that is not only central to the film’s plot and themes, but also one of the most telling quotes in recent American film history. Burt and his friends have begun to uncover the shadowy and sinister plan at the film’s center, a plan by powerful moneyed figures to overthrow the president of the United States and replace him with an unelected dictator. And Burt asks both himself and the audience, in the voiceover narration to which the film returns frequently, “What’s more un-American than a dictatorship built by American business?”

Amsterdam pulls together, fictionalizes, and at times troublingly misrepresents a number of threads from the 1930s and early 20th century American history. But that sinister plan is based on very real 1933 histories: the so-called Business Plot. Those histories reveal that Burt’s quote is both profoundly wrong and inspiringly right about the battle for American identity and ideals.

Given the entirely justified recent attention to the history of American coups, past and present, it’s quite striking that the 1933 Business Plot isn’t yet better known (Gangsters of Capitalism, a 2022 book by Jonathan Katz, who also wrote the Rolling Stone article “The Plot Against American Democracy That Isn’t Taught in Schools,” is the place to begin learning a lot more). A group of prominent American businessmen, featuring such noteworthy figures as Robert Sterling Clark and Prescott Bush, had become dissatisfied with newly elected President Franklin Roosevelt’s responses to the Great Depression, including both government programs to counter unemployment (which these figures saw as creeping socialism) and the end of the gold standard for U.S. currency (which threatened their own wealth). These men and their allies began planning for a possible coup, supported by the military and based on the rationalization that Roosevelt’s physical infirmities made him unable to perform presidential duties.

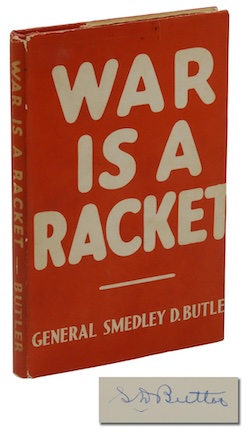

So contrary to Burt’s quote, such a plan was conceived and could indeed have happened here in America. A main reason it did not was because of the man whom the plotters approached to serve as that unelected dictator: General Smedley D. Butler (1881-1940). At the time of his death Butler was the most decorated Marine in U.S. history, having commanded the 13th Regiment in World War I as well as serving in countless other military actions in the Philippines, China, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, and Haiti. But by the 1930s he had become disillusioned with both war and the U.S. government, delivering a series of impassioned speeches to veterans’ groups and other audiences that became the basis for his subsequent book War Is a Racket (1935). Perhaps those speeches and his increasingly anti-authoritarian views led the Business Plot leaders to assume that Butler would be on their side in opposing and helping overthrow the government.

So contrary to Burt’s quote, such a plan was conceived and could indeed have happened here in America. A main reason it did not was because of the man whom the plotters approached to serve as that unelected dictator: General Smedley D. Butler (1881-1940). At the time of his death Butler was the most decorated Marine in U.S. history, having commanded the 13th Regiment in World War I as well as serving in countless other military actions in the Philippines, China, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, and Haiti. But by the 1930s he had become disillusioned with both war and the U.S. government, delivering a series of impassioned speeches to veterans’ groups and other audiences that became the basis for his subsequent book War Is a Racket (1935). Perhaps those speeches and his increasingly anti-authoritarian views led the Business Plot leaders to assume that Butler would be on their side in opposing and helping overthrow the government.

General Smedley Butler (USMC Archives)

Butler apparently shared the fictional Burt’s sentiments about the profoundly un-American nature of such plans, however. After leading the conspiracy’s members along for a time in an effort to learn more about their intentions, in November 1934 Butler began testifying about the plot to the House of Representatives Special Committee on Un-American Activities (also known as the McCormack-Dickstein Committee). At first Butler’s claims were largely dismissed in the media, with the New York Times referring to the idea as nothing more than a “gigantic hoax.” But when the committee released its report in February 1935, after more than two months of testimony and other committee hearings and investigations, Time magazine noted that “a two-month investigation had convinced [the committee] that General Butler’s story of a Fascist march on Washington was alarmingly true” and that the committee “also alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Butler, … was actually contemplated.”

Butler refused to lead and instead exposed that proposed march on Washington. Ironically, just a year earlier, he had supported a very different march on the nation’s capital. In the summer of 1932, a group of World War I veterans calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force marched from around the country to Washington, seeking long-delayed (and in the depths of the Depression, desperately needed) compensation for their military service. The participants in this “Bonus Army”” would camp in the city’s Anacostia Flats area for weeks, where they were visited and addressed by none other than Smedley Butler. Indeed, Butler and his son Thomas ate and spent the night with the veterans, and the next morning he gave an impassioned speech to the Bonus Army, calling them fine soldiers, praising their cause, and noting that they had every right to protest and lobby the government on its behalf. Unfortunately the Hoover Administration disagreed, and soon after Butler’s visit, the marchers were violently evicted and their camp was burned down. But in 1933 Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt (who had also visited the camp) offered them jobs with the newly created CCC. Amsterdam also incorporates the story of the Bonus Army; Burt and his friends are veterans themselves and advocates for veterans who had attended the 1932 Bonus March.

The Bonus Army Camp, Anacostia (Library of Congress)

Both the Business Plot’s proposed march and the Bonus Army’s achieved one were tellingly part of 1932-33 America, so I can’t entirely agree with Burt’s perspective that “What’s more un-American than a dictatorship built by American business?” That alliance of business and Fascism (abroad and at home) was a frustratingly central element of America in the 1930s. But at the same time, in the battle for America, I entirely agree with Smedley Butler — that the Bonus Army represents the best of America, in direct contrast to such creeping Fascism. As this film helps remind us, those battles are crucial parts of our past and entirely ongoing in our present.

Written by Ben Railton for The Saturday Evening Post ~ January 4, 2023