Learning more about the first Ukrainian American and his contributions to a foundational American story helps remind us that America has been profoundly transnational at every stage of its history.

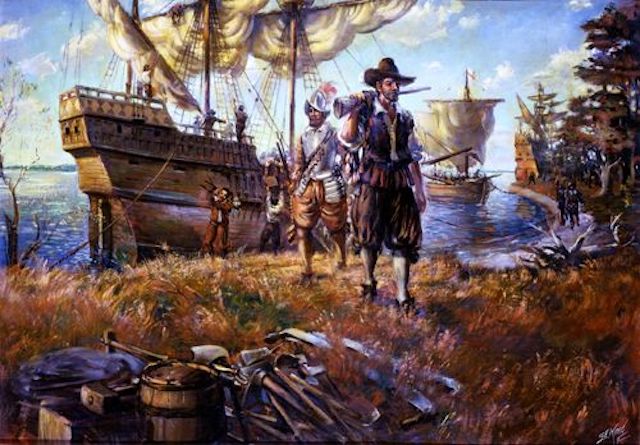

The first settlers arriving in Jamestown (National Park Service)

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine has unfolded over the last few weeks, most Americans have certainly been united in their support for the Ukrainian people and condemnation of Russia’s increasingly brutal attacks and tactics. But one area where there has been significantly less consensus is the question of whether and how the U.S. and its allies should intervene in the conflict. Among the arguments for the U.S. maintaining its distance from this unfolding European war is that this conflict is ultimately unrelated to the United States and that it concerns two foreign nations from whom we would do well to remain isolated.

There are various ways to challenge such isolationist arguments, including highlighting the historic moments when isolationism not only failed to end unfolding world wars, but also led directly to belated and more fraught U.S. involvement in those conflicts.

But there are also stories of early Americans who found their way to the continent from across the globe; these stories contradict any perspective on the U.S. as isolated from seemingly foreign nations like Ukraine. Learning more about the first Ukrainian American and his contributions to a foundational American story helps remind us that America has been profoundly transnational at every stage of its history.

That Ukrainian American, Ivan Bohdan, made his way to Virginia’s early 17th century Jamestown colony thanks to another profoundly transnational figure: Captain John Smith (1580-1631). Smith had been traveling the world since he first went to sea at the age of 16, and by the time he joined the initial voyage to the Jamestown colony in 1606 he had for over a decade been involved in countless global conflicts as a mercenary soldier. That included service to the French King Henry IV in battles against the Spanish, for the Austrian Hapsburgs in their opposition to the Romanian Prince Michael the Brave’s early 17th century campaigns, and in a series of conflicts between the Hapsburg Empire and the Ottoman Turks during the campaign known as the Long Turkish War (1593-1606).

Captain John Smith

It was during those latter experiences in particular that Smith was taken prisoner, seemingly enslaved for a time (his likely often exaggerated and always self-congratulatory reminiscences in his subsequent personal narratives are our principal source for many of these histories), and in any case spent a good deal of time in the company of Eastern European soldiers, leaders, and communities. In his final memoir The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith (1630), published just a year before his death, he emphasizes in particular the kindness with which he was received in Ukrainian (known to Smith as Podolia) communities, such as those he knew as during the period when he had escaped enslavement and was making his way through Eastern Europe. “In all this his life,” Smith writes about these experiences in the third person, “he seldom met with more Respect, Mirth, Content and Entertainment.”

Perhaps it was such fond memories of communal solidarity that led Smith to convince the colony’s governor, Captain Christopher Newport, to extend an invitation to a group of European soldiers and craftsmen whom Smith had met during his travels to join the Jamestown colony in its second full year of existence. Without doubt the colony was also in dire need of reinforcements, especially those who could contribute to its survival and growth during its very fraught early years.

Sketch of Jamestown by artist Sydney King

The first of these Eastern European settlers arrived in Jamestown in early October 1608 on the ship Mary and Margaret, part of a group known in the colony’s records simply as “8 Dutchmen and Poles” (Ukraine and many other Eastern European regions were part of the First Polish Republic, also known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth). Among them was Ivan Bohdan (sometimes spelled Bogdan), a former soldier from the Ukrainian mining town of Kolomyia who was known as a skilled producer of pitch (a product necessary for sealing wooden ships).

Little else is known for a certainty about Bohdan, but he quite likely was one of the “Polish” workers (as they have been referred to in historical documents) who went on strike in 1619 to protest their exclusion from the Virginia colony’s upcoming first election. Utilizing the slogan “No vote. No work,” these workers successfully challenged a policy that excluded non-English settlers from the election, gaining the ability to help determine the continued shape and future of the Jamestown and Virginia colonies through their votes as well as their labor. As the Virginia Company’s records document:

Upon some dispute of the Polonians resident in Virginia, it was now agreed (notwithstanding any former order to the contrary) that they shall be enfranchised and made as free as any inhabitant there whatsoever: And because their skill in making pitch and tar and soap-ashes shall not die with them, it is agreed that some young men, shall be put unto them to learn their skill & knowledge therein for the benefit of the Country hereafter.

Portrait of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe

Clearly these Eastern European settlers benefitted “the Country” and the Virginia colony in countless ways, from its earliest moments of existence through its continued growth and development across the early 17th century. In so doing, they became exemplary of the larger cross-cultural and transnational forces that helped shape the future United States throughout this period — from indigenous individuals like John Smith’s ally Pocahontas and Tisquantum in Massachusetts without whom these European settlements would never have survived; to other global travelers like Estevanico, the North African Muslim (or “Moorish”) enslaved man who accompanied Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca on his decade-long journey across the continent and became an explorer and guide in his own right throughout the Southwest; to English figures like John Smith himself, whose journeys continued across the Americas and helped shape much of the early 17th century.

It’s not enough to note that 21st century America is fully connected to a global society. The fundamental fact is that long before there even was a United States, the evolving community here has been transnational, featuring individuals from across the globe who have contributed crucially to every stage of our history. Whatever actions we choose to take on the global stage in 2022, however we choose to express our solidarity with Ukraine, it’s long past time we recognized that America has always been defined by transnational stories like that of Ukrainian American Ivan Bohdan.

NOTE: On this day, I post this historical history lesson in honor of my wife, who was born in post-WWII Germany of Ukrainian parents. Her family migrated to Venezuela some years later when they were found by her Uncle Walter – a successful businessman, who lived in Detroit. The family was then migrated to America and a year later settled in Chicago. I met my wife 12 years later (on a blind date) and we were married in October of 1970 – and we remain together. ~ Jeffrey Bennett, Editor

Written by Ben Railton for the Saturday Evening Post – March 17, 2022