An aspiring fraud put in years of hard work to become a nobleman — and still failed.

When it comes to big frauds, many names may come to mind: Charles Ponzi’s measly take of $10 million, Bernie Madoff and his $65 billion pyramid scheme, or Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay’s $74 billion accounting scam at Enron.

When it comes to big frauds, many names may come to mind: Charles Ponzi’s measly take of $10 million, Bernie Madoff and his $65 billion pyramid scheme, or Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay’s $74 billion accounting scam at Enron.

One other name should be included in this company: James Addison Reavis. No other fraudster worked as hard as Reavis. And none of them could match the size of his deception.

We’re not talking about the $5.3 million he received for phony investments and land sales — it would equal a paltry $173 million in current dollars. No, we’re talking the size of his fraud in miles: Reavis’s crooked land claim ran from Phoenix, Arizona, to Silver City, New Mexico — at 18,600 square miles, an area twice the size of Vermont.

He referred to it as the Peralta land grant, or the “Barony of Arizona,” and he backed his claim with fake historic documents from Mexican and Spanish archives.

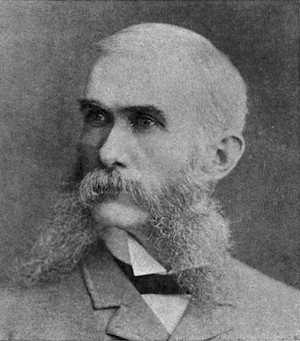

The face of the new American nobility: James Addison Reavis, the Baron of Arizona (Wikimedia Commons)

Reavis was born in 1843 in Missouri and grew up speaking English and Spanish. He served briefly in the Confederate army, but when his superiors found him forging their signature on passes, he deserted and joined the Union army.

After the war, he worked as a streetcar conductor, a salesman, and a store clerk before opening a real estate office. He soon found a new use for his forging skills. He could obtain land of unknown ownership for his clients by counterfeiting 18th century Spanish titles. (The U.S. was bound by several agreements with Mexico to honor Spanish deeds to lands.)

Reavis started his climb into big-time fraud when he met George M. Willing, a prospector who had bought a Spanish land grant from someone named Miguel Peralta years before. In 1871, The two men began researching the grant, searching for official documents that could back up the claim of title.

In 1874, while Reavis was on his way to California to obtain further documents, Willing travelled to Prescott, Arizona to file his claim. The following morning, he was found dead. (The Saturday Evening Post’s account of Reavis’s adventures — “The Red Baron of Arizona” by Clarence Budington Kelland from the October 11, 1947, issue — implies that Reavis might have poisoned Willing. But Reavis was at sea at the time.)

Reavis travelled to Prescott and took possession of Willing’s papers. In 1881, he obtained Willing’s interest in the grant and now began adding details that established its sizable boundaries. The original grant Willing had claimed was only 2,000 square miles. Under the forging hand of Reavis, this grew to nine times that size.

Reavis travelled to Washington D.C., Guadalajara, and Mexico City to research the Spanish royal documents. In fact, he was forging papers and inserting them into the authentic files.

He created a fictional, original Baron of Arizona: Don Miguel Nemecio Silva de Peralta de la Córdoba. And he now had papers that proved the title had passed to Willing, and then to himself.

In 1882, Reavis filed papers to show Willing’s deed had been assigned to him. The following year, he made an official claim, bringing with him two trunks full of wills, codicils, and proclamations from the fictional life of the first Baron.

Certain business interests in Arizona realized that Reavis’s claims could cause the titles to their land to be declared void. To avoid such a problem, the Southern Pacific Railroad paid him $50,000 for a right of way through “his” land. And the Silver King Mining Company paid Reavis $25,000 to buy back the title to their mine. Both of these transactions made Reavis’s claim seem more credible.

He now hired rent collectors and agents who would sell quitclaims to the people living on the land Reavis now said was his. If residents of the “Peralta Grant” claim didn’t contact his lawyers, they would be charged with trespassing and, when the U.S. government authenticated the claim, expulsion. Some immediately abandoned their homes and lands.

The Arizona surveyor general’s office sent an expert to Guadalajara to authenticate Reavis’s claims. Reavis accompanied him and led him to all the documents he wanted him to see, which included documents he’d forged. The expert’s report, not surprisingly, favored the claim.

But Arizona’s surveyor general, Royal A. Johnson, found problems with the documents. They lacked the Spanish king’s signature and there were no corroborating records. Then the territorial attorney general filed suit in 1884 to settle title issues affecting his personal property. Under questioning, Reavis gave vague answers about his finances. When he lost the case, Arizonans celebrated and Reavis left for California.

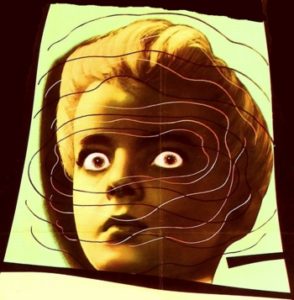

His knew that his title rested on a bewildering line of conveyances that made his claim seem doubtful. His new approach was to produce an heiress to the Peralta grant. While on a train, he saw a young woman who might look the part and struck up an acquaintance. She was a servant at a California ranch who had no record of her birth. Reavis made her his ward and announced she was, in fact, Baroness Sofia Loreto Micaela, the last living descendant of the original Baron Peralta. Reavis enrolled her in a convent school, where she would be trained to comport herself as a lady.

Reavis’s fake baroness wife (Wikimedia Commons)

When Reavis married her, he claimed the title “Baron of Arizona” on the strength of his wife’s make-believe pedigree. Travelling to New York, Reavis talked influential New York politicians and bankers into supporting his claim. An industrialist gave him a sizable stipend that enabled Reavis to travel to Spain in style and search for records to back his claim.

While in Spain, he was treated like the royalty he claimed to be. The Spaniards were delighted to see someone of Spanish heritage taking so much territory away from the Americans.

Meanwhile, he was busy forging documents and inserting them into court records of the Spanish aristocracy. Returning to America, he filed a claim for his wife’s inherited lands.

In 1889, Royal Johnson was reappointed Arizona’s surveyor general and ordered by the acting commissioner of the land office to re-open the inquiry into the Peralta grant.

Johnson reported the claim was a fraud. The documents supporting the claims showed misspellings and bad grammar. They were printed on different paper than documents of the 1700s. They were written with modern pens instead of quills, and they lacked corroborating documents from Spanish sources. Some sections of writing had been erased or written over.

But Reavis now had the U.S. secretary of the interior and a senator supporting his claim. In 1890, he sued the government for failing to rule on the Peralta claim.

In Santa Fe, the U.S. Court of Private Land Claims recruited a Mexican-born New York lawyer, Severo Mallet-Prevost, to investigate the claim’s documentation outside the U.S.

Searching records in Mexico, he challenged the validity of every paper he found supporting Reavis. In Spain, he learned that Reavis had been inserting forged documents into the Madrid archives. Another member of the land claims court found a man in Los Angeles who had been promised money from Reavis for testifying to the existence of one of Mrs. Reavis’s fictional relatives.

As evidence mounted against Reavis, his lawyers began withdrawing from the case, encouraged, perhaps, by the fact he had no more money. However, over 100 people who were related to a real Miguel Peralta showed up to demand part of Reavis’s fortune.

As the hearings proceeded, experts testified that they had found pages had recently been glued into archives from the 1700s, and that the name of Peralta only appeared on official papers over an area that showed marks of erasure. The birth records of the “Baroness” had been inserted into one church record but not in an index stored separately.

The court now heard that, while in Spain, Reavis had been caught trying to steal official documents out of the archives in Seville. He had been seen copying and altering old documents.

At last the court ruled his claims fraudulent. Stepping outside the courtroom, he was arrested by a U.S. Marshal and charged with attempted fraud.

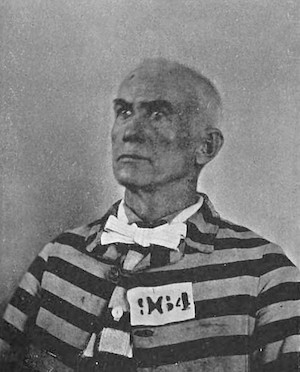

Shorn of his sideburns, his reputation, and his freedom, James Addison Reavis nonetheless could hold an expression of outraged nobility. (Wikimedia Commons)

Reavis’s wealthy supporters had all abandoned him, and he spent a year in jail awaiting trial, where he was found guilty. He was sentenced to two years in federal prison and a fine of $5,000.

Upon his release, he worked at several land development projects in Arizona, but businessmen wanted no part of him. He died poor and forgotten.

Like all successful con men, Reavis had the ability of convincing strangers of his honesty, good will, and authenticity. Several prominent attorneys and politicians had backed his claims and supported him in his fight for the Peralta Grant.

But Reavis also had the determination to hunt down documents in the U.S., Mexico, and Spain and painstakingly alter them.

During his trial in federal court, a supporter said, “It is impossible that any one man could have forged all the signatures in this case. Reavis would have had to forge over 200 Spanish documents and signatures. No man could have done it. It is the most improbable thing conceivable.”

But that’s what he did.

Written by Jeff Nilsson For The Saturday Evening Post – November 22, 2022

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE: