the American Revolution

The Battle of Long Island – August 27, 1776

The Battle of Long Island – August 27, 1776

We had our American Revolution over two centuries ago and the years have done something to it. The legends remain, and the statues and the grassy earthworks and the great body of tradition, but a good deal of the reality has been filtered out – revised! When we look back to see Washington crossing the Delaware on a cold winter night, or kneeling in prayer in the snow of Valley Forge; we see the Minutemen, or a lanky Virginian rifleman picturesque in fringed buckskin; but somehow it all seems out of a pageant, and neither Washington nor the men who followed him quite come alive for us.

This is a pity, because the central reality in this great act that brought a nation to its birth was the living, aspiring, struggling people who were immediately involved in it. A romantic haze has settled down over the whole affair, and when we look through it the facts tend to be a little blurred. And what is most worth remembering – the one thing that so often escapes us – the fact that like all of history’s wars, the war of the American Revolution was a hard, wearing, bloody and tragic business – a struggle to the death that we came very close to losing.

It was a struggle, furthermore, that was fought out by people very much like ourselves; which is to say that they were often confused, usually divided in sentiment, and now and then rather badly discouraged about the possible outcome of the tremendous task they had undertaken. It comes as a shock to realize how many Americans in 1775 were actually opposed to independence and a break with King George III. A good many historians believe that no more than a third of the provincials were active patriots; and they estimate that another third were Loyalists, with the remaining third uncommitted. To continue, it is clear that good many of the people who believed in independence were not always willing to fight for it. When the war began, the colonies contained about 2½ million men, women and children – a population, which should have yielded some seven hundred thousand men capable of bearing arms. Yet in 1780, only one year before the crucial battle at Yorktown, the Continental Army and the state militia together contained no more than one sixteenth of the country’s available manpower.

But all of this says nothing more than the people of the Revolutionary period were extremely human. Enough of them in the end, were willing to fight and die for what they believed in to make the dream of independence and freedom come true, and we who look back at them owe a debt of whose size is almost beyond our comprehension. They did not have an easy time of it, and if they got confused and discouraged now and then it is not to be wondered at.

For behind the great struggle with the professional armies of Great Britain, there

was the unending struggle between patriot and Loyalist, a civil war just as real and as bitter as the one which broke out nearly a century later. And although the principal battles were decided along the eastern seaboard, the fighting on the frontiers, along the rim of American civilization, was, if anything, even more violent, and continued in many areas long after the peace treaty with England was signed.

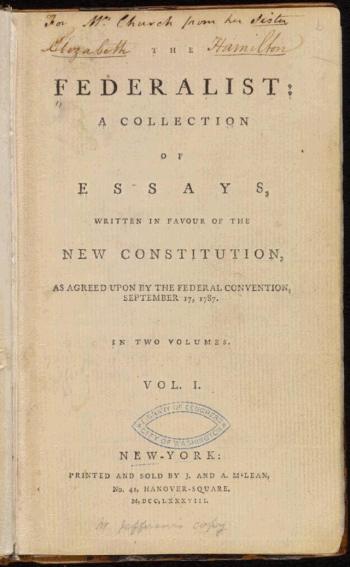

Federalist Papers, Thomas Jefferson’s copy

Sometimes, it is hard to see how Americans could have won if the revolution had not turned into a world war – that is, if France had not intervened in the wake of the surrender of Burgoyne’s army – and yet there was an unconquerable toughness at the core of the American effort. The farmers and shopkeepers of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and North Carolina and the other colonies were hard men to beat, and they went quite a way on their own, without any help from anyone but themselves. They knew little about the European methods of warfare – and despite all the tales of frontier riflemen fighting Indian style from behind trees, most of the great Revolutionary battles were fought according to the European style. We were poorly equipped, usually ill fed, and almost certainly badly clothed; but fighting against the world’s greatest power, they managed not only to hold off disaster – but usually gave a little better than they got.

Somewhere, in the course of more than six bitter years of warfare, those Americans worked something out. They began to see, amidst the monotony, discomfort, acute danger, suffering and constant campaigning, that they were somehow more than just soldiers of the separate colonies. Somewhere, through their efforts – because of their efforts – a nation was born. As South Carolina’s Christopher Gadsen had urged before the fighting had started, they began to see that, “There ought be no more New England men, no New Yorkers . . . but all of us Americans!“

That came – and finally independence came after – as it had to come once the vision had truly taken hold.

. . . and what follows is this special intellectual battle which led to the formation of the Law of the Land – our Constitution! ~ KML