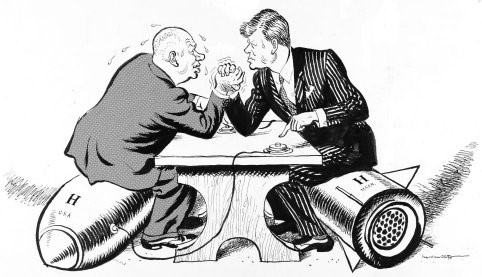

President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev took the measure of each other when they met for the first time, in Vienna in 1961. (Google Images)

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. This moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Among the American people—if not historians—John F. Kennedy regularly ranks as one of the best presidents in various opinion polls. There is, undoubtedly, something magnetic about the Kennedy administration, dubbed “Camelot” by the president’s wife, Jacqueline, soon after his assassination. However, one wonders if sentiments like this are little more than postmortem nostalgia for a young, handsome president. JFK memorialization and mythology are such that it seems the memories contain something for everyone. Today, mainstream liberals tout his efforts on civil rights; defense hawks laud the toughness of his Cuban Missile Crisis stand; conversely, antiwar types insist that Kennedy was about to pull the U.S. troops out of Vietnam when his presidency was ended by an assassin’s bullets. To the scholar, however, much of the passionate praise for JFK seems unwarranted for a short administration that boasted so few tangible accomplishments.

A detached, probing view of the Kennedy years elucidates a generally popular president who was nevertheless a conventional Cold Warrior, a tool of the military-industrial complex, forever stalled on domestic legislation and reactive rather than proactive on black civil rights. This Kennedy—the human president—was also a highly political creature, motivated as often by partisan rancor and opinion polls as by the national interest. It is this Kennedy who fell into the Cold War-era trap that ensnared all Democratic presidents since and including Harry Truman; ever since Truman was accused of having “lost China,” a string of Democratic executives (that by no means ended with JFK) became obsessed with conveying “toughness,” avoiding the well-worn “Munich analogy” of appeasement, and out-hawking the Republicans in foreign affairs. It was a highly insecure Kennedy who escalated the doomed American war in Vietnam and terrorized Cuba’s popular government throughout his 34-month administration.

Perhaps forever, Americans will remember these words from Kennedy’s sunlit inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country. … Ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.” It is the final, less famous, clause in this passage that rings as problematic and, ultimately, hollow. From the perspective of a working-class Cuban, a Vietnamese peasant or an unemployed, disenfranchised black American, JFK was no champion of man’s “freedom.” Rather, he hedged on African American civil rights, accelerated warfare in Southeast Asia, cut taxes on the wealthiest Americans and obsessed himself with overthrowing the Castro administration in Cuba.

Our story, though, must not center only on the singular figure of Kennedy. “Camelot” went far beyond a compelling, photogenic politician, and far beyond his attractive wife and children. JFK assembled a team of youthful, energetic, elite advisers—many of them academics—forever christened the “best and the brightest.” Kennedy made a show of crafting this highly educated team, which included Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, national security adviser McGeorge Bundy, Secretary of State (and Rhodes scholar) Dean Rusk, informal adviser and Harvard professor Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and his brother Robert “Bobby” Kennedy as attorney general. Two of Kennedy’s choices might seem peculiar for a supposedly liberal administration—McNamara and Bundy were Republicans. The oddness did not stop at politics: The appointment of Bobby was unashamedly nepotistic, and the vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, was a rough-hewn—some would say crude—Southerner. Despite the odd mix, the glossy aura of the team seemed to stick, especially in Americans’ collective memory.

Let us consider, now, how this group of the “best and brightest” led an optimistic generation of Americans into leaving so much undone at home, blundering further into an unwinnable war and bequeathing an ever more dangerous world.

Rethinking Kennedy, as such, is also to normalize and provincialize him. Some will find much left to like about this less glamorous Kennedy, others far less. Regardless, this—the Kennedy of history, not fantasy—is the president who must inform America’s present moment.

Looks and Charm: Riding Charisma Into the White House

It began with a debate; with television cameras, to be more exact. Kennedy faced off against Richard Nixon, an anti-communist hawk and Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, in the 1960 presidential election. Theirs was only the second televised U.S. presidential debate in history, and it mattered, as nearly all Americans (90 percent) now had a TV set. It was Sept. 26, 1960, and the face-off between the two candidates was broadcast live on CBS, NBC and ABC. It was an uneven fight. Nixon, though a highly skilled debater, had been sick (and hospitalized) for 12 days and was less prepared than usual. Nevertheless, most Americans who listened on the radio thought Nixon—trained in high school debate—had “won.” The more numerous TV viewers, however, favored Kennedy—freshly tanned and seemingly cool and composed—over Nixon, who appeared unshaven (he had refused to wear any heavy makeup).

The common memory of the 1960 election tends to contrast the youthful Kennedy (43 years old when he was elected) with the old Washington hand Nixon—but the vice president was only three years older than his rival! The coarse, insecure and petulant Nixon was seen by many as lacking style, making Kennedy seem the much younger man. Nixon had “no class,” JFK had said, and a Washington Post editor (and Kennedy supporter), Ben Bradlee, claimed that Nixon had “[n]o style, no style at all.” In the end the race was tight, one of the closest popular votes in American history, with JFK counting just a 13,000-vote margin of victory. So close was the election that Nixon believed the vote had been rigged and seriously considered contesting it. He may well have been right: Evidence existed for fraud in Illinois and Texas (Democratic vice presidential candidate Lyndon Johnson’s home state). “We won, but they stole it from us,” Nixon would say, and none other than a 13-year-old member of the Young Republicans named Hillary Rodham would volunteer to search for such fraud in Chicago.

That Kennedy would ultimately prevail seems obvious to modern readers. He has become, after all, a “liberal” phenomenon. Yet this was less than clear at the time. Indeed, JFK seemed, in 1960, a lukewarm choice for most Democrats in the party’s left wing. Progressives distrusted him due to his silence—and at times support—of McCarthyism when Kennedy was a senator. Others, Eleanor Roosevelt for instance, resented that black civil rights had not seemed a priority for Sen. Kennedy. Journalist Eric Sevareid of CBS complained of the Kennedy image itself, noting that Jack and his advisers were all “tidy, buttoned-down men … completely packaged products. The Processed Politician has finally arrived.” The Massachusetts senator’s wealth also drew the ire of some on the left. After losing to JFK in the key West Virginia primary contest, the prominent Minnesota senator (and later Johnson’s vice president) Hubert Humphrey complained, “You can’t beat a million dollars. The way Jack Kennedy and his old man [the multi-millionaire Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.] threw money around, the people of West Virginia won’t need any public relief for the next fifteen years.” This much was certain: The Kennedy of 1960 was no reincarnation of FDR. Such hagiography only came later.

Kennedy also ran a dirty, dishonest campaign. He campaigned against the outgoing incumbent Eisenhower administration from the right. He crowed about a nuclear “missile gap” with the Soviets—which was, by implication—Vice President Nixon’s fault as well—even though he had been told by high-ranking defense officials that none existed. Kennedy went with the lie. In reality, the U.S. then possessed overwhelming nuclear superiority; it counted the equivalent of 1,500 atomic bombs and 3,000 planes capable of carrying atomic bombs, while the Soviets had only 50 to 100 missiles and just 200 long-range bombers. It didn’t help that the gentlemanly Eisenhower kept mostly quiet: He refused to divulge the classified information that would have disproved the “gap”—and provided only lukewarm support for his vice president. In truth, Ike never much cared for Nixon.

Beyond Kennedy’s “redbaiting” over the nonexistent “missile gap” and his composure at the television debate, the candidate’s success was bolstered by his image. He inspired frenzy at campaign rallies, where groups of people—mainly women—jumped barriers and chased his car. A prominent journalist at the time, Haynes Johnson, described Kennedy as “the most seductive person I’ve ever met.” It was this mystique, a carefully cultivated portrait, that helped nudge JFK over the finish line. Personal appeal mattered! The historian Jill Lepore has concluded that “Kennedy prevailed, in part, because he was the first packaged, market-tested president, liberalism for mass consumption.” Furthermore, she noted that JFK certainly “looked more like a Hollywood movie star than like any man who had ever occupied the Oval Office.” So, for better or worse, it was John Kennedy who took the national helm in January 1961.

After the inauguration, the Kennedy family continued to awe the media and refined American elites. As the historian James Patterson noted, many reporters (themselves often liberal) “lavished attention” on the king and queen of Camelot. Jack had “unparalleled access” to the media, and he used it well. He was the first president to allow his press conferences to be televised live, and within six months some 75 percent of Americans had watched one. Among these TV viewers, 91 percent reported a favorable impression of Kennedy’s performances. The telegenic first lady, Jackie, 31 years old when her husband was elected president, would also proudly show off to reporters, and eventually America’s TV viewers, the elegant ways in which she redecorated the White House. Furthermore, the first couple made sure to invite famous artists, musicians, writers and other celebrities into their official home. No doubt this cultivation contributed to the fact that although he had serious politically opposition, Kennedy remained personally popular throughout his short tenure. This son of great wealth seemed to represent the hopes, dreams and sanguine ambition of an entire people. Whether Americans were duped—then and now—is another question entirely.

Great Expectations: A New Frontier at Home?

Although JFK is revered as a specifically liberal icon by most American Democrats and independent progressives, his actual record hardly warrants such a label. On the surface, of course, high expectations for legislative success seemed more than appropriate. The Democrats had captured both houses of Congress and the Oval Office in 1960, after all. Newsweek predicted that Kennedy would enjoy a “long and fruitful ‘honeymoon’ with the new Democratic 87th Congress.” Kennedy, Newsweek continued, “will find Congress so receptive that his record might well approach Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous ‘One Hundred Days.’ ” Furthermore, the magazine noted that with the capable House Speaker Sam Rayburn in place, and the former Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson on board as VP, matters couldn’t have been more favorable for the new administration.

It was not to be, and such dramatic and hyperbolic predictions would seem foolish within precious few years. Sure, the fervent Kennedy would count some modest early accomplishments. His creation of the Peace Corps encouraged a spirit of selflessness and international service in a hopeful young generation. Speaker Rayburn also ushered through Congress a small bump in the federal minimum wage and modest public funding for job training in depressed areas such as Appalachia. But that’s about it for “liberal” social and economic legislation. Most of the rest of Kennedy’s agenda was either blocked by Congress’ many conservatives, both Democrats and Republicans, or proved to be far more amenable to the political right than to the left. Furthermore, the supposedly enlightened Kennedy administration actually appointed fewer women to high-level federal postings than did his predecessors. His Cabinet, in fact, was the first since Herbert Hoover’s not to include a single woman. JFK, in short, was no political reincarnation of Franklin Roosevelt.

When it came to economics, for example, Kennedy was rather centrist and—for the times—right of center. His tax cut dropped the top marginal rate on individuals from 91 percent to 70 percent, and corporate rates from 52 percent to 48 percent. His predecessor, the Republican Eisenhower, had maintained higher taxes. Observers noted that the tax cut, though sold otherwise, mainly benefited the most well-off Americans. The only thing particularly Keynesian about Kennedy economics was the deficit-spending largesse he rained upon the military-industrial complex. Rapid increases in defense spending, as they usually do, provided a short-term bump for the health of the economy and lowered unemployment.

Kennedy’s domestic failures can be attributed to a combination of factors. Firstly, Jack was never very enthusiastic about “kitchen-table” issues. Even when he was in Congress (where he was known as a less-than-average senator and not particularly hard-working), his passion was for foreign policy over domestic issues. As president, Kennedy quickly tired of domestic affairs and never much cared for the more liberal lawmakers, referring to them as “honkers” and refusing to court them personally. This was apparent from the outset. As his adviser Theodore Sorensen diligently worked on the inaugural address, JFK burst in and exclaimed, “Let’s drop the domestic stuff altogether.” And he did! This famous speech is notable for almost completely ignoring homefront issues. This focus continued throughout his presidency. Kennedy, in fact, once noted to Nixon—of all people—that “[f]oreign affairs is the only important issue for a president to handle, isn’t it? … I mean, who gives a shit if the minimum wage is $1.15 or $1.25, compared to something like Cuba?” No doubt millions of U.S. workers did.

Congress, as it existed in the early 1960s, was stacked against the new president. The Democratic caucus was far from united. Indeed, the party was already coming apart—even if it would take later developments in civil rights and the Vietnam War to irrevocably break it. Conservative Southern Democrats continued, as they had since the latter part of the New Deal, to form reactionary coalitions with far-right Republicans. This alliance was usually strong enough to either vote down or fatally filibuster a liberal bill. And, since almost all leadership assignments in Congress were based on seniority and Southerners generally faced no Republican challengers in elections, the powerful committees were usually chaired by conservative Southern Democrats. These committee heads often “buried” progressive—especially civil rights—legislation and refused to bring bills to the floor for open debate and voting. It was this coalition between Southern conservative Democrats and their Republican colleagues that killed all the potential laws favored by Kennedy’s progressive base, including health insurance for the aged and the creation of an urban affairs department.

Finally, Kennedy, though seen as “tough” on foreign affairs, didn’t demonstrate much courage on seminal domestic matters. He usually hedged bets and avoided controversy in order to bolster his image and avoid political losses for himself or for his party at the ballot box. Raised in a highly competitive family, JFK also hated to lose. Pressured by liberals in his party to fight for key legislation, he said, “There is no sense in raising hell, and then not being successful. There is no sense in putting the office of the presidency on the line on an issue, and then being defeated.” Only in the “manly” matters of foreign affairs would Jack go “all in!” As such, whatever the claims of his defenders, JFK’s legislative record was rather weak. Just 10 days before the assassination, The New York Times noted that “[r]arely has there been such a pervasive attitude of discouragement around Capitol Hill. … This has been one of the least productive sessions of Congress within memory.” Kennedy’s politicized caution in legislative decision-making had real consequences for certain desperate constituencies in America—none more prominent than African Americans fighting for civil rights.

Hope and Despair: Kennedy and Civil Rights

The partisans and apologists for the mythical Kennedy and his posthumous promoters cling to the false belief that as a Northern “liberal,” JFK was some sort of civil rights crusader. That he was not. Though Kennedy was, at times, genuinely horrified by the most overt Southern bigotry—and particularly shocked by images of young black protesters being attacked by police dogs in Birmingham, Ala.—for the most part the president hedged his bets and treated civil rights like any other political issue. He rarely stuck his neck out for the cause, and he took the side of righteousness only when it was politically palatable, or absolutely necessary, to do so.

The story of Kennedy and civil rights began with his 1960 presidential campaign. During the run-up to the 1960 election, the young civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was imprisoned in Georgia for a minor traffic violation and sentenced to four months at hard labor. This draconian punishment was an obvious attempt to stifle the black civil rights movement, and African Americans and Northern liberals led a large public outcry. Both major-party presidential candidates felt the need to take action. Nixon worked behind the scenes to quietly intervene with Georgia’s governor but said nothing publicly. Kennedy, however, after receiving a telephone call from King’s wife, Coretta, decided to publicly express sympathy while brother Bobby telegraphed the judge and demanded King’s release. The move succeeded, and King was soon out on bail. The Kings and their backers were thankful and seem to have urged some black voters to back Kennedy in the November election. Whatever the cause, black voters chose the Democrats by a margin seven points higher than they had in 1956, potentially swinging a few key Northern states to Kennedy. Indeed, Eisenhower was later quoted as attributing the Republican defeat to “a couple of phone calls.”

But what motivated the Kennedys? That would remain to be seen. Civil rights activists, by the early 1960s, were becoming angrier about the slow pace of social and political change in America. The author James Baldwin summed up the feeling in 1961: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage all the time.” In that spirit, an increasing number of black students affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) took “freedom rides” on interstate buses throughout the South in order to test the recent court integration orders. In Alabama and Mississippi, the riders were brutally attacked time and again. Their leaders pleaded for federal protection from the new Kennedy administration. Such protection wasn’t initially forthcoming and arrived only slowly. Attorney General Robert Kennedy would later defend his slow reaction by blatantly lying, stating that he had not been notified beforehand about the protests.

In response to the “freedom rides” and other ongoing civil rights protests, the Kennedys generally remained in a cautious reactive mode. After all, though their hearts were—partly—sympathetic to the movement, they were still Democrats in the 1960s. As such, they feared the ire of the prominent and powerful Southern faction within the party and the loss of its votes. Jack would, no doubt, make many symbolic moves that improved on the civil rights record of the proceeding administration—hiring more blacks in federal jobs, appointing five African Americans as federal judges, including Thurgood Marshall, and instructing the Justice Department to heavily increase its oversight of voting rights cases. Nonetheless, more often, political considerations stifled Kennedy’s action on civil rights. He worried about formidable Southerners in Congress such as Sen. James Eastland of Mississippi, chair of the important Judiciary Committee. In fact, as a favor to Eastland, Kennedy would appoint four ardent bigots to federal judgeships in the Deep South. One of these judges once described African Americans in his courtroom as “niggers” and compared them to chimpanzees.

Furthermore, JFK took precious little tangible executive or legislative action during his first two years in office. He refused to introduce a civil rights bill—part of the 1960 Democratic platform—in 1961-62 and reneged on his campaign promise to declare an executive order to integrate federal housing. He would wait, he decided, until after the 1962 midterm elections before issuing the housing order or introducing a civil rights bill (the legislation would not pass until after his death). The bottom line remained the same as ever: Kennedy lacked passion for any domestic affairs, including civil rights, and moved forward only ever so cautiously on these issues.

Indeed, at times the president and his attorney general were concerned that the civil rights movement was moving too fast, and they sought to slow down racial unrest. During the height of the “freedom rides,” President Kennedy yelled to an aide, “Tell [the riders] to call it off!” When the riders refused, Kennedy called for a “cooling-off period.” This wouldn’t do for the activists, and CORE chief James Farmer retorted that African Americans “have been cooling off for 150 years. If we cool off any more, we’ll be in a deep freeze.”

Nor would Kennedy protect Martin Luther King Jr. from the obsessive hatred and harassment of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover, convinced that King was a Soviet-run communist (he wasn’t), asked Attorney General Robert Kennedy to allow the bureau to tap the civil rights leader’s phones. Bobby acquiesced, and Hoover developed a “blackmail file” full of King’s sexual infidelities. (The FBI found that King and his staff had little to no connection with radical socialists.) Historians still speculate over why the Kennedys acquiesced to Hoover’s unwarranted harassment of King. What seems clear is that Hoover—who assiduously acquired dirt on all Washington figures—had one heck of a file on JFK. He knew about Kennedy’s extramarital affairs, including one with Judith Campbell—also the mistress of a Mafia gangster—and of the president’s concurrent collusion with the U.S. mob to assassinate Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

When Kennedy did worry about civil rights he did so cautiously and mainly out of foreign policy concerns. He feared that the U.S. could not lead the “free world” effectively if the Soviets could point to a hypocritical America that mistreated its black citizens. It was here that the issues of the Cold War and civil rights collided. So it was, then, in the aftermath of the police chief of Birmingham, Ala., unleashing dogs and water cannons on peaceful black protesters that Kennedy finally gave the order to prepare a civil rights bill and gave his most inspiring speech on race:

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities. … If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant … if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote … if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?

This was, no doubt, a powerful and persuasive bit of oratory, but even after the speech Kennedy remained cautious and sought to temper the movement. Indeed, many rights activists thought Kennedy’s bill was too late and didn’t go far enough—in fact, it did only cover desegregation of public facilities without addressing voting rights. It dealt, too, only with de jure segregation while ignoring de facto housing denials, police brutality and employment discrimination. Thus, when the bill went forward—and got caught up in the expected filibuster of Southern congressmen—civil rights activists continued (against the president’s will) to take direct actions.

Most famously, in May 1963, a coalition of civil rights leaders organized what they dubbed a massive March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (in their historical memory, Americans tend to, instructively, omit the “jobs” portion of that title). The march was designed to force legislative action by shutting down the capital through prolonged sit-ins by many thousands of demonstrators. Young radicals, such as John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), also planned to join seasoned leaders (like MLK) on the stage and make fiery addresses. Kennedy and his brother were panicked, and they labored, effectively it turned out, to tone down the march. Older black moderates compromised under pressure from the president, and, in line with an agreement reached between the administration and the organizers of the protest, the march was limited to one day, liquor stores were closed and demonstrators were required to dress in “respectable clothing.” Kennedy aides even read the proposed speech of the firebrand Lewis and forced other black leaders to seek to soften the SNCC leader’s message and tone at the last moment. Lewis was furious but agreed. Had he not, administration officials stood ready to disconnect the public address system. Still, the march would go down as an important event in American history. It is celebrated by centrist “liberals” to this day.

Nonetheless, at the time many young black activists felt stifled and were frustrated by the lack of tangible results from the event. It didn’t change intransigent Southern opinions on Capitol Hill, and according to Sen. Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, “had not affected a single vote” on the proposed, and stagnated, Civil Rights Act. To the more radical demonstrators, the event had been a sellout of the movement: Its leaders, they charged, were little more than “Uncle Toms.” The fiery Black Muslim Malcolm X labeled it the “Farce on Washington” and declared:

It was the grass roots out there in the street. It scared the white man to death, scared the white power structure in D.C. to death. … They [the Kennedys] called in these national negro leaders that you respect and told them, ‘Call it off!’ And Old Tom [MLK] said, ‘Boss, I can’t stop it because I didn’t start it. … I’m not even in it, much less at the head of it.’ And that old shrewd fox [JFK], he said, ‘If you ain’t in it, I’ll put you in it. I’ll put you at the head of it. I’ll endorse it. …’ This is what they did with the March on Washington … they joined it … they took it over. And as they took it over it lost its militancy. It ceased to be angry. It was a sellout. It was a takeover.

Malcolm X may have been hyperbolic and impassioned, but he wasn’t exactly wrong, either. The march had been, on some levels, precisely as he described. Kennedy’s adviser and later biographer Arthur Schlesinger Jr. admitted as much when he described Kennedy’s civil rights strategy and achievements in the wake of the march. “So in 1963,” he wrote, “Kennedy moved to incorporate the Negro revolution into the democratic coalition. …” To some extent he did, but at what cost? Undoubtedly, this co-opting of existing civil rights efforts contributed to sanitizing and de-radicalizing a vibrant grassroots movement.

So it was, when an assassin took the president’s life, that his proposed Civil Rights Act—like JFK’s entire record on this moral issue—remained in political deadlock on Capitol Hill. It would take a new president and ever more public sacrifice from grassroots black activists to get the act through. Kennedy could, and ultimately would, only do so much for racial equality in segregated America.

To the Brink: Kennedy’s Cold War

A 1962 British political cartoon by Leslie Gilbert Illingworth, published right after the Cuban Missile Crisis, depicts President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev locked in confrontation. Their fingers are poised above buttons that would set off the hydrogen bombs they are sitting on.

In his abbreviated administration, Kennedy would fulfill his dream of being an ardent Cold Warrior, pressing the Russians and combating communism the world over. In this way, whatever his defenders later surmised, Kennedy was little different than—and was perhaps more hawkish than—his predecessors and successors. He regularly escalated crises, and, along with the foolish Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, brought the planet to the brink of destruction. JFK would leave behind an ever-colder Cold War, and he did little to usher in even a modicum of detente with the Soviets. The tragic part, the disturbing bit, is that Kennedy—an astute student of foreign affairs—seems to have known better; to have known that communism was no global monolith, that the Soviets and Chinese were actually enemies, that, in fact, the U.S. had a nuclear program far superior to the Soviets’. Even so, with such knowledge in hand, Kennedy went ahead anyway—whether due to his insecurity, political fortunes or toxic notions of masculinity—and faced off against the Russians at every turn and in many places.

Kennedy had already presented his simplistic views on the campaign trail. “The enemy,” he said, “is the communist system itself … increasing in its drive for world domination. … It is also a struggle for supremacy between two conflicting ideologies: freedom under God versus ruthless, godless tyranny.” Despite the obvious flaws, hyperbole and factual inaccuracy of this Manichean worldview, Kennedy would use his often-quoted inaugural address to lay out America’s resultant plan of action. “We shall pay any price,” he exclaimed, “bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” And, in a sense, Kennedy would have American troops, diplomats and spies do just that. What was less clear was whether the subjects, targets and victims of America’s liberty burden had desired U.S. intervention in the first place. Individual and collective notions of freedom and liberty are often complex, subjective and prisoners of context. In Kennedy’s (at least public) view there was no room for such nuance.

The Cold War only heightened under JFK for a number of reasons. One was his personal style as a competitive, aggressive statesman unwilling to back down. Another was the continued and growing power of a military-industrial complex that stepped up its demands for more contracts, more weapons and more cash throughout the administration. Finally, there was the provocative and often foolish behavior of Kennedy’s counterpart, Soviet Premier Khrushchev. Perhaps bolstered by recent successes in nuclear and space technology, or due to Kremlin readings of Kennedy’s youth and inexperience, Soviet policy during the Kennedy years was particularly combative, especially in the so-called Third World.

Kennedy took some of his action based, no doubt, on political considerations. In the election campaign he had run, dishonestly of course, against Eisenhower’s supposed “missile gap” and weakness toward the Soviets. Thus, the new president rolled out a strategy, known as “flexible response,” as a rebuke of Ike’s notion of “massive retaliation”—reliance on nuclear weapons over conventional war. Flexible response simply meant that the U.S. would maintain the capability and stated intent to check the Soviets anywhere, on any level, from diplomacy to espionage to limited war to outright land war to an apocalyptic nuclear exchange. In truth, however, the new strategy was little more than a gift to the Pentagon and arms industry. To wit, a pre-inaugural task force on national security determined that significant defense spending increases were both desirable and necessary. Such spending, even if it weren’t necessary, the task force concluded, would be a boon to the national economy—a sort of defense Keynesianism or military welfare state. The report concluded that “[a]ny stepping up of these [defense] programs that is deemed desirable for its own sake can only help rather than hinder the health of our economy.” Over the next three years, the military budget would grow 13 percent, from $47.4 billion to $53.6 billion. Defense spending for defense spending’s sake was to be the mantra of the Kennedy years.

If JFK loved and was enamored by the military—he famously formed the “Green Berets” Army Special Forces unit to conduct counterinsurgency missions, keeping a beret on his desk—he could barely stomach diplomats. For him, the diplomats at the State Department were little more than “striped-pants boys” who did little but shuffle papers. Indeed, as an undersecretary of state in the Kennedy administration complained, the president and his team were “full of belligerence” and “sort of looking for a chance to prove their muscle.” Kennedy (and Khrushchev) would ensure there was opportunity for that to happen. JFK also funded many other expensive ventures related to national security, such as the Apollo program—announced in response to the Soviet launch of its Sputnik satellite—to put U.S. astronauts on the moon. Though celebrated in retrospect, the U.S. space program cost $35 billion before an American set foot on the lunar surface in 1969 but produced, according to historian James Patterson, “relatively little scientific knowledge.” As a competition with the Russians, however, Apollo proved quite popular with the American people, and Kennedy knew it.

In his Cold War adventures, Kennedy—like many politicians of his postwar generation—became obsessed with the vague notion of “credibility,” the idea that anything that smacked of compromise with the Soviets displayed only “weakness,” or “softness,” and was comparable to Britain and France’s ignominious Munich deal with Hitler in 1938. For example, in preparing for a May 1961 summit meeting with Khrushchev, he said, “I’ll have to show him that we can be as tough as he is. … I’ll have to sit down and let him see who he is dealing with.” For JFK, it was a toxic vision of a face-off between alpha males on a world stage … with nukes. This flawed and simplistic thinking grounded just about every Kennedy decision in world affairs from 1961 to 1963. It would bring the world to the brink of destruction in the Cuban Missile Crisis and suck the U.S. military into a disastrous, unwinnable war in Vietnam. But that was yet to come.

Kennedy’s first disaster came in Cuba. And here the backstory mattered. Fidel Castro, a popular communist insurgent leader, had—in a direct threat to American business interests—overthrown the dictatorial U.S.-backed Batista regime in 1959. At that time, U.S. corporations controlled 80 percent of Cuba’s utilities, mines and oil refineries, 40 percent of its (mainstay) sugar industry and 50 percent of its railways. Furthermore, the Italian-American Mafia controlled many lucrative Cuban casinos. Once in power, the populist Castro confiscated millions of acres from the American United Fruit Co. and set up national systems of housing, education and land redistribution. These programs were highly popular among Cuban peasants, many of whom had suffered greatly under the U.S.-backed dictatorship. In response, the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations pressured the International Monetary Fund not to lend much needed money to Cuba. Unsurprisingly, in response, Cuba signed trade agreements with the Soviets, who agreed to buy all of the sugar crop—a crop that previously had gone mostly to the United States and that the U.S. was now refusing to buy.

So it was that Eisenhower and the even more Castro-obsessed Kennedy decided to destabilize and eventually overthrow the revolutionary Cuban government. All this, particularly the later U.S.-sponsored mercenary invasion, was a violation of the law. President Harry Truman’s earlier treaty with the Organization of American States had proclaimed that “[n]o state or group of states has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatsoever, in the internal or external affairs of another state.” And, for the public record, the new American president—though he knew of ongoing plans to invade Cuba—seemed to admit as much. Kennedy told a press conference that “there will not be, under any conditions, any intervention in Cuba by United States armed forces.” It is true, of course, that when the Bay of Pigs invasion came it was mostly conducted with dissident Cuban mercenaries. Nonetheless, Americans piloted the supporting attack planes, armed the fighters and served as CIA spy liaisons leading up to and during the invasion. And, when four Americans piloting those planes were shot down and killed, the U.S. government refused to tell the families the truth about how their loved ones had died.

In addition to approving the disastrous Eisenhower plan to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy’s administration had actually considered even more drastic, immoral action. The Joint Chiefs of Staff, in fact, proposed Operation Northwood—a plan to conduct “false flag” terror attacks killing American civilians and then blame the deaths on Cuba—in order to drum up support for war. Kennedy and other civilian leaders refused to back the outlandish plan. However, its existence and acceptance by the top military service chiefs demonstrated the paranoia, frenzy and Cuba-obsession of the era.

Kennedy should have known better than to go through with the invasion. He hadn’t planned it himself, first of all, and had been given much dissenting advice from within his own administration. Arthur Schlesinger was against it, as was the liberal Adlai Stevenson, a two-time Democratic presidential candidate and Kennedy’s ambassador to the United Nations. So was the Marine Corps commandant, who warned that Cuba was 800 miles long and hard to conquer. As was the respected Sen. J. William Fulbright, who presciently predicted in a memo to the president that “[t]o give this activity covert support is of a piece with the hypocrisy and cynicism for which the U.S. is constantly denouncing the Soviet Union.” So too was Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles, who wrote Secretary of State Dean Rusk that “[o]ur national interests are poorly served by a covert operation. … This would be an act of war.” And so it was.

Though Cuban nationals would serve as ground troops in the ill-fated invasion, U.S. Navy destroyers escorted the landing crafts and U.S.-piloted planes provided the pre-emptive bombing raids. It wasn’t enough. Castro was tipped off by spies and even U.S. press reports and was prepared. Furthermore, the Cuban civilians living near the landing site were highly supportive of the generally popular Castro; there would not be—as the CIA and dissidents had wrongly predicted—an uprising around the Bay of Pigs. Within 24 hours Cuban fighters and Soviet-made tanks operated by Cubans checked the invasion and inflicted heavy casualties on the attackers. Most surrendered, many were killed.

When the dissidents realized they were in serious trouble they requested additional airstrikes, and a stoic but rattled Kennedy balked. For this some U.S. military leaders would never forgive him. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer, called the decision “reprehensible” and “almost criminal.” This was an overstatement. What the military brass seemed unable to comprehend was that Cuba’s new leader was popular, and no token force of a mere 1,400 dissidents (only 100 or so trained soldiers) could overthrow Castro. That would have required a direct U.S. military commitment and a risk of war with Russia. In reality, Kennedy was, not for the last time, poorly served by the assessments of his Pentagon and CIA spymasters. The Bay of Pigs fiasco was their failure as much as that of the actual invaders.

Still, Jack and Bobby Kennedy wouldn’t quit. The brothers seemed genuinely obsessed with Castro and determined to save face and win back the ever-vital “credibility” they had lost in the Bay of Pigs. Jack would put Bobby, the attorney general, personally in charge of the secretive Operation Mongoose, a CIA-coordinated program to damage the Castro regime. “My idea,” Bobby said, “is to stir things up on the island with espionage, sabotage, general disorder.” And indeed he did, as agents contaminated Cuban sugar exports, bombed factories, led paramilitary raids and attempted (33 times) to assassinate a sovereign head of state, Castro. All of this was illegal under the Truman-era treaty or any standard application of international law, and it constituted, truthfully, state terrorism.

The unintended consequences of U.S. bellicosity toward Cuba were manifold. The Bay of Pigs failure heightened tensions with the Soviets and added a personal pugilism to the rivalry between Kennedy and Khrushchev. Furthermore, the U.S. neo-imperial invasion whipped up Cuban nationalism and increased Castro’s popularity. Furthermore, both Cuba’s leader and his ally Khrushchev were now certain the Kennedy administration intended to invade the island with U.S. forces and depose the government. Castro pleaded for help and got it. Soon after the Bay of Pigs action, the Soviets began sending thousands of military personnel to the island and by the spring of 1962 had armed Cuba with missiles, some of them nuclear. A new, ever more dangerous crisis would result.

It must be said, first, that Khrushchev, ultimately, had foolishly blundered in secretly stationing nuclear missiles just 90 miles from Florida. The net gain to his ability to strike the United States homeland was far too negligible to warrant the risk of a U.S. invasion, airstrike or even an accidental escalation by either side of the conflict. He was placing Soviet credibility on the line, on the global stage, with neither an effective exit strategy nor the (thank God) willingness and intent to actually wage nuclear war. For these and other perceived failures, eventually, the Soviet Politburo would remove the premier and replace him in 1964.

Still, one can—given the context—understand Khrushchev’s motives. The United States had been the illegal aggressor in the failed invasion of Cuba and seemed intent on overthrowing a Soviet ally; besides, the U.S.-led NATO military alliance had long encircled the Soviet Union with nuclear-armed bases adjacent to Russian territory. Should the U.S. really go berserk over one such base in the Caribbean? As he stated before the Cuban Missile Crisis, Khrushchev argued that “[t]he Americans surrounded our country with military bases and threatened us with nuclear weapons. Now the Americans will learn what it feels like to have enemy missiles pointed at you.” He wasn’t wrong, but that didn’t make his move in Cuba a smart play.

Kennedy would later be memorialized for his cool handling of the ensuing Cuban Missile Crisis, and it must be admitted that he did ignore his more bellicose advisers and ultimately avoid a nuclear war. Still, he operated within rather narrow bounds of imagination, and must bear some of the responsibility for how close the world came to destruction. In many ways he got lucky. Firstly, JFK never even seriously considered early advice from liberals in his own party like Adlai Stevenson, who recommended immediate, reasonable compromise: foreign demilitarization in Cuba, a no-invasion pledge by the U.S., a removal of Soviet missiles followed by a concurrent removal of similar U.S. missiles in Turkey. After all, Stevenson asked, why risk nuclear war over a few missiles in Cuba when both great powers already possessed enough long-range ICBMs to destroy the other many times over? But the Kennedys would have none of it. They wouldn’t “appease” the Soviets.

Besides, there were political considerations. Congressional midterm elections were imminent, and JFK couldn’t have the Republicans attacking him from the right for being “soft” on Russia. No, he decided, there would be no secret tit-for-tat deals—he would publicly denounce the Soviet move and place a naval quarantine around the island. There would be no further shipments of Soviet military equipment, and Khrushchev would have to be the one to back down. It ultimately worked out, of course, despite many close calls (the shooting down of a U.S. spy plane pilot, and the timely refusal of a Soviet submarine captain to fire a nuclear torpedo when a U.S. Navy destroyer targeted his vessel with what turned out to be non-lethal depth charges), and thus we forget how dangerous a move Kennedy had made. Absolute terror gripped the world before the Soviet ships approaching the quarantine turned around and Khrushchev eventually folded. The famous American evangelist Billy Graham even preached about the “end of the world” during the crisis. America’s NATO allies were terrified equally by the escalatory moves of the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

To the president’s credit, Kennedy was not taken in by the staggering lunacy of many of his advisers, especially some in the military. His national security adviser and his vice president called for immediate (no warning) airstrikes on the Cuban missile sites. So, eventually, did every single member of the military’s Joint Chiefs of Staff. Jack opposed them, as did Bobby, who astutely noted, “We’ve talked for 15 years about a first strike, saying we’d never do that.” To launch such a strike would make his brother the “Tojo of the 1960s,” Bobby said in referring to the official who was Japan’s prime minister and head of the military at the time of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

What’s interesting, in retrospect, is that eventual agreement hashed out between the Soviets and the Americans ultimately resembled the early deal that the “dovish” Stevenson had proposed. The Soviets would pull out all the nuclear weapons, and the U.S. would lift the quarantine and promise not to invade the island (though, the record shows, it did continue its espionage and harassment). That was the public end of the deal, the one that made the USA look strong and allowed Kennedy to boast that he had “cut his [Khrushchev’s] balls off!” But secretly, Kennedy had actually opened negotiations to remove U.S. mid-range missiles from Turkey—which were becoming obsolete anyway. The weapons were indeed removed by April 1963.

Kennedy’s military advisers, in particular, were incensed by the deal. Air Force Gen. Curtis “Bombs Away” Lemay crowed “We’ve been had!” to the president’s face and banged on the table. The deal was, he exclaimed, “the greatest defeat in our history. … We should invade [Cuba] today!” It wasn’t—by any stretch of the imagination—but for Lemay (the war criminal who had firebombed Japanese civilians in 1945) and an entire generation of military intellectual mediocrities groomed in the early Cold War, the deal was a personal defeat, a lost chance to use their “toys” in a once-and-for-all shootout with the Ruskies! As for the (mainly civilian) deaths that would ensue if the great powers did go to war over Cuba, that mattered not, according to another Air Force general, Thomas Power, who thundered to the president, “Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards. … At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win.” It was this level of absurdity from some of his most senior advisers that Kennedy had to deal with. This, too, helps explain history’s kinder view—in hindsight—of JFK’s crisis leadership.

The president, even if his blunders and aggression toward Cuba had ultimately caused the crisis he “solved,” did seem to learn one valuable lesson from the standoff: Don’t trust the military! The military and CIA had called for open invasion and escalation during both the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis. They, along with many of Kennedy’s civilian advisers, seemed genuinely prepared to fight it out with the nuclear-armed Soviets over a relatively small Caribbean island. Speaking about the Joint Chiefs’ unanimous advice to bomb and invade Cuba, Kennedy curtly remarked, “These brass hats have one great advantage, if we … do what they want us to do, none of us will be alive later to tell them they were wrong.” And, finally, late in his presidency, JFK also had something important in mind that he never got the chance to impart. “The first thing I’m going to tell my successor,” he explained, “is watch the generals, to avoid feeling that just because they’re military men, their opinions on military matters are worth a damn.” He was an intelligent man, Jack Kennedy, capable of complex thinking and great achievements. His flashes of brilliance and lucidity—such as this appraisal of his military leaders—demonstrate his potential.

Unfortunately, as substantiated in both the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, he was just as apt to cause as solve a crisis. He avoided escalation of the ill-advised mercenary invasion he green-lighted; he called off the military attack dogs when they sought to start a war over a missile crisis he and his flawed Cold Warrior mentality helped cause. Such were the tragedies and triumphs of John F. Kennedy—stuck in the Cold War box and unable to escape his outdated conceptions of masculinity and toughness, as well as his competitiveness and insecurity.

* * *

Kennedy’s blunders included the escalation of the war in Vietnam. He would continue to back a corrupt South Vietnamese regime that lacked legitimacy and funnel ever more military advisers into the country until there were some 16,000 on the ground. He even tacitly backed an illegal military coup that overthrew and murdered the formerly U.S.-backed president of South Vietnam. In essence, Kennedy’s Cold War bellicosity and flawed Manichean worldview would—just as they almost sparked a nuclear war over Cuba—lead the U.S. inexorably deeper into its greatest military fiasco and defeat in a place few Americans could find on a map: Vietnam. But that is a story best told comprehensively across several administrations, and it will be the topic of our next segment in the series.

What, then, must we conclude about Kennedy? Perhaps a comparison is in order. Like a later young president who promised hope and possessed both a handsome family and cultivated taste—Barack Obama—Kennedy seemed the polite, enlightened choice for the self-styled elites. His knack with the media, his pop culture chic and his propensity to surround himself with the famous and the celebrated invoked praise and admiration from America’s supposed cultured class. This style, this image, allowed many Americans to ignore his relative lack of substance. What, truly, did Kennedy do to improve life for impoverished peasants in the Third World, disenfranchised and terrorized blacks tilling sharecrop soil or suffering in urban ghettos, for the long-oppressed people of Cuba, for, well, anyone in real need? The answers can be argued. What is clear is that it is time to re-evaluate Kennedy and hold him to the same standard as presidents who were not martyred. His death was a tragedy among America’s population, but for countless millions across the world, so was his presidency.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• H.W. Brands, “The Devil We Knew: Americans and the Cold War” (1993).

• Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001).

• Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018).

• James T. Patterson, “Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974” (1996).

• Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Written by Maj. Danny Sjursen for Truthdig ~ April 6, 2019

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE: