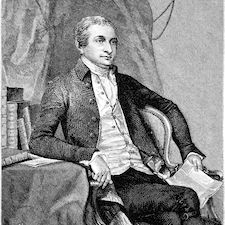

On December 12, 2017, one of America’s most prominent, yet forgotten, Founding Fathers would have turned 272 years old. John Jay, a native of New York City, had among the most impressive resumes in American history, especially among the Founding Fathers who never became president. Jay served in the Continental Congress, as a diplomat representing the United States in the Treaty of Paris, an author of the Federalist Papers, America’s first chief justice, acting secretary of state under George Washington, and governor of New York.

On December 12, 2017, one of America’s most prominent, yet forgotten, Founding Fathers would have turned 272 years old. John Jay, a native of New York City, had among the most impressive resumes in American history, especially among the Founding Fathers who never became president. Jay served in the Continental Congress, as a diplomat representing the United States in the Treaty of Paris, an author of the Federalist Papers, America’s first chief justice, acting secretary of state under George Washington, and governor of New York.

Yet despite this illustrious resume, Jay’s name is often overshadowed by his contemporaries. For instance, although Jay wrote five Federalist Papers, his coauthors, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, wrote the most famous and treasured, such as Federalist 10 and Federalist 51.

Likewise, Jay may have been the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, but he only held the office for a few years during a time when the Court was far and away the weakest and least-prestigious branch of the government. Consequently, Jay’s name is overshadowed by the great John Marshall, the chief justice who asserted the Court’s power of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison, transforming the Court into a co-equal branch.

Perhaps the biggest reason Jay is relegated to the second tier of Founding Fathers, in spite of his numerous positions and indelible contributions, was a treaty Jay negotiated in the (aptly named) Jay Treaty. As successful as Washington’s presidency was, the French Revolution and resulting wars threatened to tear the country apart. These conflicts, particularly the Franco-British War, even reached into Washington’s cabinet, with Thomas Jefferson supporting the French (and their revolution) and Alexander Hamilton supporting the British.

Jay, as chief justice, was given the unenviable task of negotiating a way to keep America out of the conflict in a way that would appease Americans on both sides of the issue. Washington dispatched Jay to Great Britain to secure a treaty that would ensure the continuation of America’s trade relationship with the British without dragging the nation into a military conflict. Jay’s treaty was, on the whole, successful in attaining both objectives.

In spite of Jay’s success, public reaction to the treaty was as polarized as could be. Hamilton and the rest of the pro-British Federalists praised the treaty. The Jeffersonians, however, denounced the treaty in the strongest possible terms, asserting it to be a repudiation of the American Revolution’s republican values in favor of Britain’s monarchical system, as well as a betrayal of the French. The Jeffersonians unleashed their wrath on Jay, assailing him as a monarchist and burning him in effigy—Jay is purported to have mournfully noted that he could traveled from one end of the country to the other guided only by their light.

In spite of Jay’s success, public reaction to the treaty was as polarized as could be. Hamilton and the rest of the pro-British Federalists praised the treaty. The Jeffersonians, however, denounced the treaty in the strongest possible terms, asserting it to be a repudiation of the American Revolution’s republican values in favor of Britain’s monarchical system, as well as a betrayal of the French. The Jeffersonians unleashed their wrath on Jay, assailing him as a monarchist and burning him in effigy—Jay is purported to have mournfully noted that he could traveled from one end of the country to the other guided only by their light.

In the long-run, Washington and Jay would be vindicated by their commitment to neutrality. As the French Revolution spiraled out of control, even Jefferson would eventually reconsider his support. Still, Jay’s popularity never really recovered, and in the decades since his image was burned in effigy by half the country, his name has been consistently overshadowed by such names as Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Franklin, Madison, and Marshall.

His unpopularity aside, Jay clearly made a mark on the nation’s founding, one that deserves more recognition than being the answer of a few trivia questions. So, here at the Miller Center, we would like to wish a happy (272 and counting) birthday to a truly consequential Founding Father.