The details of legendary pioneer Davy Crockett’s death have been told by many sources — Some Questionable!

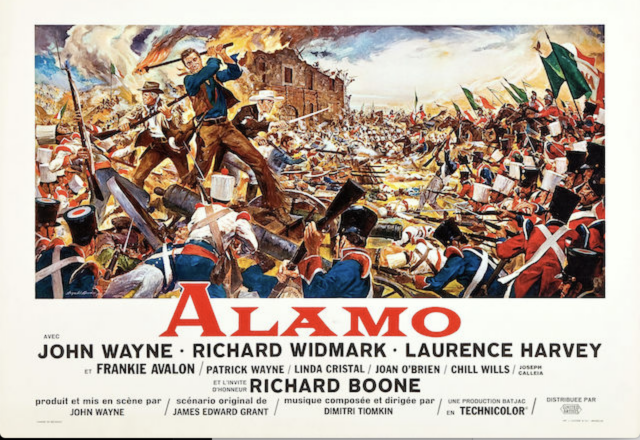

Each year around March 6, the anniversary of the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, the question arises as to how Davy Crockett died. It is not enough to know that he died. We need to know exactly how this legendary American lost his life in one of our nation’s most famous battles. Thankfully, there were eyewitnesses.

A letter to the New-Orleans Commercial Bulletin a month after the Alamo’s fall confirmed Crockett’s death. It quoted Joe, slave of Alamo commander William Barret Travis, “Davy Crockett died like a hero, surrounded by heaps of the enemy.” Another paper also cited Joe, specifying Crockett and friends “were found lying together, with 21 of the slain enemy around them.”

An actual description of Crockett’s death emerged three months later in the Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer. The reporter quoted an unidentified Mexican source who claimed Crockett and five others had been surrounded and ordered to surrender by General Manuel Castrillón. They did so only to be executed on General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s orders. Mexican officers killed them with swords.

September 1836 saw a variation in Detroit’s Democratic Free Press. George M. Dolson, in a letter to his brother, described a secret meeting after the Mexican defeat at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. The only ones present were Colonel James Morgan, in charge of Mexican prisoners on Galveston Island, captive Mexican Colonel Juan N. Almonte and Dolson as interpreter. In this account Castrillón again captures Crockett and five others alive. This time Santa Anna orders them shot. That Almonte did not require an interpreter and was not even on Galveston Island on July 19, the date the interview was said to have taken place, has never bothered anyone.

Four years later Edward Stiff, in his adventure narrative The Texas Emigrant, cited a servant of Santa Anna. This servant (a black American named Ben) accompanied the general into the Alamo, where he saw “no less that 16 dead Mexicans around the corpse of Colonel Crockett and one across it with the huge knife of Davy buried in the Mexican’s bosom to the hilt.”

Four years later Edward Stiff, in his adventure narrative The Texas Emigrant, cited a servant of Santa Anna. This servant (a black American named Ben) accompanied the general into the Alamo, where he saw “no less that 16 dead Mexicans around the corpse of Colonel Crockett and one across it with the huge knife of Davy buried in the Mexican’s bosom to the hilt.”

Colonel James H. Perry, a member of Sam Houston’s staff at the Battle of San Jacinto, reported a different story in 1842 and hinted it had come from a black servant (Joe?) from the Alamo. Crockett cheered on his companions until just he and six others were left. The Mexicans called on them to yield, but Crockett shouted in defiance, leaped into the crowd of soldiers below and rushed out toward the city. He held at bay two pursuing soldiers for a time, “until he was finally thrust through by a lance.”

San Antonio civilian Candelario Villanueva testified in 1859 that he entered the Alamo and recognized Crockett’s body. That same year Dr. Nicholas Labadie cited Colonel “Urissa” (Fernando Urriza), describing the solo execution of a “venerable looking old man,” who was shot by a file of soldiers. “I believe they called him Coket [sic],” Urriza recalled.

Francisco Antonio Ruiz, alcalde of San Antonio at the time of the battle, said in 1860 that he and others had found Crockett’s body “toward the west, and in a small fort opposite the city.”

Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson Hannig recalled in 1875, “I recognized Colonel Crockett lying dead and mutilated between the church and two-story barrack building and even remember seeing his peculiar cap lying by his side.”

Sergeant Francisco Becerra provided yet another variation on the execution story, endorsing as fact notes prepared by an interviewer and read to him. In the version to which Becerra agreed, a firing line of Mexican soldiers execute Crockett along with Travis. The soldiers were so wildly enthusiastic that they killed or wounded eight of their comrades in the process.

The San Antonio Daily Express printed a story in 1889, supplied by a professor George W. Noel, of an account by Mexican soldier Felix Nuñez. Nuñez described the death of a tall American wearing a long buckskin coat and “a round cap without any bill and made of fox skin, with the long tail hanging down his back.” A lieutenant felled this man with a sword blow above the right eye after the American had killed or wounded at least eight Mexican soldiers. Soldiers then pierced the prone man with at least 20 bayonets. Crockett is not mentioned by name, but he is the only Alamo soldier ever identified as having traveled to Texas wearing such a cap.

In 1890 Madam Candelaria (Andrea Castañón de Villanueva), wife of Candelario Villanueva and an Alamo survivor claimant, gave an account claiming Crockett was among the first to fall while advancing from the church toward the wall. He ran “slowly and with great deliberation, without arms,” when a volley caused him to “fall forward on his face, dead.”

Three years later William James Cannon provided a unique Crockett death scene in a letter to Texas Governor James Stephen “Big Jim” Hogg. Cannon, a boy in 1836, claimed he had escaped from the Alamo during the battle with Madam Candelaria. Crockett was lying prone about 15 feet away and tossed a piece of paper to them as they ran by. Cannon retrieved it, escaped and secreted it away for a month. The note clearly showed Crockett’s priorities were not in fighting and/or dying. It read: “Let the goddess of the free dedicate an altar. Make it of the materials of the Alamo. Let these stones speak, that their immolation not be forgotten. The blood of heroes has stained them.”

In 1896 Eulalia Yorba recalled Crockett in death lying beside a dying man whom she was attending. Crockett’s coat and woolen shirt were so soaked with blood that “the original color was hidden.” She speculated that “the eccentric hero must have died of some ball in the chest or a bayonet thrust.”

Madam Candelaria’s story changed in an article that appeared shortly after her death in 1899. In the posthumous account Crockett stood in a door looking “grand and terrible” and fighting a column of Mexican infantry. After he fired his last shot, he swung either his rifle or a sword over his head. A heap of dead lay at his feet as the Mexicans lunged at him with bayonets until he fell.

Educator-historian William P. Zuber reported another execution story. This time Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos told Dr. George M. Patrick who then told Zuber that he—Cos, that is—discovered Crockett alone in one of the Alamo rooms. He then brought Crockett to Santa Anna and interceded on his behalf. When Santa Anna ordered Crockett’s execution, the Tennessean lunged at him with a dagger, and a soldier killed Crockett with a single bayonet thrust to the heart.

Educator-historian William P. Zuber reported another execution story. This time Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos told Dr. George M. Patrick who then told Zuber that he—Cos, that is—discovered Crockett alone in one of the Alamo rooms. He then brought Crockett to Santa Anna and interceded on his behalf. When Santa Anna ordered Crockett’s execution, the Tennessean lunged at him with a dagger, and a soldier killed Crockett with a single bayonet thrust to the heart.

In 1907 Enriqué Esparza, a child survivor of the Alamo, stated that Crockett fought to his last breath. “He fell immediately in front of the large double doors which he defended with the force that was by his side. …There was a heap of slain in front and on each side of him. These he had all killed before he finally fell on top of the heap.”

The story of Mexican soldier Rafael Soldana came to light in 1935 via Creed Taylor via historian James T. DeShields in his book Tall Men With Long Rifles. Soldana described a man later identified as “Kwockey” who stood to the left inside a door in the Alamo and plunged his knife into the chest of every soldier who tried to enter. Finally a well-directed shot broke Kwockey’s right arm. He then grabbed his rifle in his left hand and used it as a club until a point-blank volley killed him.

An unidentified Mexican captain also in DeShields’ book said Crockett stood in a room and used his gun as a club until a shot broke his arm. The Mexicans then rushed the room. Davy parried their bayonet thrusts with a large knife in his left hand and killed several soldiers before falling.

The “diary” of Lieutenant José Enrique de la Peña, published in Mexico in 1955, alleged that David Crocket (sic) was one of seven Texians taken alive and executed on Santa Anna’s orders. This time Mexican officers killed them with swords.

Generalisimo Santa Anna

A handwritten account by “Santa Anna” appeared the following year in Man’s Illustrated. This version has the Mexican general finding Crockett among the survivors. The Mexicans dispose of them “instantly, after a brief interrogation.” Crockett, in this interrogation, revealed that up to 30 Texians mutinied, and had they not, “We would have held you off from now until Armageddon.” Crockett died before revealing how the mutiny had been suppressed. The mute answer lay in a pile of dead Texans in the middle of the compound. All had been shot in the chest, as if executed.

De la Peña’s “diary” resurfaced in 1975, this time published by a university press in the United States. The format, time and place proved a perfect fit for languorous historians who needed only to thumb the pages of this book to know conclusively how Crockett died—taken alive and executed by the swords of Mexican officers. This in spite of the fact there is no provenance of this “diary” before its 1955 appearance, not one page of the manuscript is in de la Peña’s authenticated handwriting, and a number of passages are almost identical to other accounts only made public after de la Peña’s death in 1840.

So, yes, thanks to such eyewitnesses, we know exactly how, when and where Davy died.

William Groneman III