Today’s high school students may yawn when they hear teachers describe what a world-changing document the United States Constitution was when it was ratified in 1788 and a new government was formed a year later in 1789.

Today’s high school students may yawn when they hear teachers describe what a world-changing document the United States Constitution was when it was ratified in 1788 and a new government was formed a year later in 1789.

But a deeper look behind the scenes reveals the three dramatic innovations the Founding Fathers introduced in just 4,400 words that changed the course of history for the better over the next 228 years, not just in the United States of America, but around the word:

Part I. A Single Written Agreement Was Now the Highest Authority for “The Rule of Law” in America.

Two-thirds of the four million residents of the United States in 1789 (67 percent) were of British ancestry. Another 14 percent were from other parts of Europe. Nineteen percent (750,000) were from Africa, the vast majority of whom (700,000) were slaves, although a small number (50,000) were free. (We’ll have more on this later in another article in our Constitution Series.)

All of the thirteen original states who ratified the United States Constitution were former British colonies.

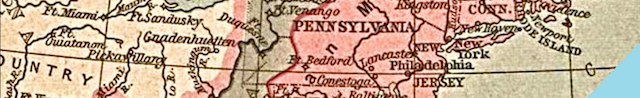

A map of the thirteen colonies that comprised British North America in 1767 (Maine was part of Massachusetts and Quebec, was a province, not a colony, acquired by Great Britain from France just a few years earlier). (click to see the whole picture)

As a consequence, the government of the new United States was based on what the British called “the rule of law” — the idea that the country was governed by laws that applied to everyone, not by the arbitrary decision of one or a select group of leaders. “The rule of law” is one element that distinguishes both a republic and a constitutional monarchy from a dictatorship, an absolute monarchy, or a pure democracy.

Great Britain during the era of the Founding Fathers had a population of fourteen million, and consisted of three kingdoms on the island of Britain–England, Wales, and Scotland-united under a single government whose head of state was the king and whose laws were established by the elected Parliament, and a fourth kingdom-Ireland- on the island of Ireland that was a “client state” of the kingdom of England. By 1801, all four kingdoms would be united under one country, known as The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The kingdoms of England, Wales, and Scotland on the island of Britain and the kingdom of Ireland on the island of Ireland, circa 1789. (click to see the whole picture)

Great Britain had a long tradition of respect for “the rule of law,” dating back more than nine hundred years before the American Constitution–thirty generations–to the time of the Anglo-Saxon King Alfred the Great, who created not only the country of England by uniting the ancient lands of Wessex, Anglia, Mercia, and Northumberland, but also put together the first codification of English law in the “Doom Book.” (The final unification of England was accomplished by Alfred’s grandson, King Aethelstan, around 927 A.D.)

King Alfred the Great, circa A.D. 872, as portrayed by actor David Dawson in the BBC television series The Last Kingdom. (click to see the whole picture)

The first eight decades of the settlement Colonial British North America took place as the mother country, Great Britain, underwent its own dramatic transformation from a nation that was on the verge of becoming an absolute monarchy to one that was firmly established as a constitutional monarchy.

In 1607, when the first British settlement in North America was established in Jamestown,Virginia, Great Britain was ruled by King James I, who conducted himself as an absolute monarch and considered Parliament–the country’s elected legislative body whose tradition stretched back to the thirteenth century and beyond–as an annoyance to largely be ignored.

By 1689, when local residents of the colony of Massachusetts successfully revolted against a tyrannical governor put in place earlier by King James II, William & Mary had assumed the throne of Great Britain as constitutional monarchs who agreed to Parliamentary supremacy.

British subjects living in the mother country celebrated this Glorious Revolution–the political uprising that began in 1688 and placed William & Mary on the throne in 1689–as a restoration and advancement of the traditional British concept of “the rule of law.”

The new Parliament elected after the Glorious Revolution passed a new law–the Bill of Rights of 1689 (often called the English Bill of Rights, not to be confused with our own Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, all of which were ratified by 1791.) – that defined the terms of this new constitutional monarchy, and protected the individual liberties of British subjects wherever they lived in the world. The agreement was hailed on both sides of the Atlantic.

Newly installed monarchs William & Mary receive a copy of the Bill of Rights of 1689 from a representative of Parliament. (click to see the whole picture)

British subjects living in Colonial British North America–which by this time had a population of 250,000–celebrated the ascendancy of a constitutional monarchy as well.

John Locke, an influential English political philosopher whose ideas were central to rise of a constitutional monarchy and whose writings profoundly influenced the thinking of many of the Founding Fathers, summed up the concept of “the rule of law” that held sway in the minds of British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean at the time.

John Locke’s arguments, as articulated in Two Treatises of Government made sense to the Founding Fathers. (click to see the whole picture)

“Freedom is constrained by laws in both the state of nature and political society,” Locke wrote in a book called Two Treatises of Government, first published in 1689.

“Freedom of nature is to be under no other restraint but the law of nature. Freedom of people under government is to be under no restraint apart from standing rules to live by that are common to everyone in the society and made by the lawmaking power established in it,” he said.

“Persons have a right or liberty to (1) follow their own will in all things that the law has not prohibited and (2) not be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, and arbitrary wills of others,” Locke concluded.

Locke’s ideas made a lot of sense to the Founding Fathers, all of whom were born well after those words were written (the oldest Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706, more than 17 years after the Glorious Revolution) but began their intellectual journeys fully on board with the British concept of a constitutional monarchy.

Had the mother country adhered to those principles, there would have been no need for an American Revolution.

But, as it turned out, Parliament and King George III began to treat British subjects in British North America differently than it treated British subjects living in Great Britain.

Great Britain (now the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) has never had a single document that defines its Constitution. In fact, until the ratification of the American Constitution in 1789, no country in the history of the world ever had a single document that served as its highest authority for “the rule of law.”

A famous English legal scholar by the name of A.V. Dicey wrote a book in the late 19th century in which he argued that England (and by extension Great Britain and now the United Kingdom) has, in fact had a Constitution for centuries, but it is not found in a single document. Instead, it is comprised of the combination of laws passed by Parliament, the common law (the collective judicial decisions of the courts over hundreds of years), “parliamentary conventions,” such as the one that enacted the reforms of the Glorious Revolution, and “works of authority,” such as the document signed in 1215 by King John and the barons of England known as The Magna Carta.

Dicey is probably correct in that assertion, but the fluid nature of the “English Constitution,” and the ability of Parliament to pass laws that changed what it said without giving proper consideration to the views of British subjects living in British North America was the ticking time bomb just waiting to explode during the second half of the 18th century.

And explode it did.

In 1765 Parliament passed the Quartering Act, which forced colonists to provide lodging to British soldiers living among them, and the Stamp Act, which placed an unwelcome tax on all newspapers, legal documents, and other printed documents in the colonies.

This 1768 print by Paul Revere depicts the landing of British troops in Boston Harbor. (click to see the whole picture)

The colonists, with good reason, believed that these laws completely disregarded their rights as British subjects.

Then in 1767, Parliament passed even more onerous laws, known collectively as the Townshend Acts, which imposed more unwelcome taxes on the colonists, including the now infamous tax on tea.

In late 1767, a series of articles entitled “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” began to appear in publications throughout the thirteen colonies. Penned by John Dickinson, who two decades later would serve as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, these essays presented a compelling case that the imposition of taxes on the colonies by Parliament without their consent was unconstitutional–defining the English constitution as the new agreements about governance in Great Britain arising from the Glorious Revolution almost eight decades earlier. That sentiment was widely shared in the colonies.

“Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” were significant because they first advanced the constitutional argument for independence from Great Britain. (click to see the whole picture)

The usurpations of the liberties of the colonists by Parliament kept piling up.

“With a good deal of surprise I have observed that little notice has been taken of an act of Parliament, as injurious in its principle to the liberties of these colonies as the Stamp Act was: I mean the act for suspending the legislation of New York,” Dickinson wrote in one of his letters.

“The assembly of that government complied with a former act of Parliament, requiring certain provisions to be made for the troops in America, in every particular, I think, except the articles of salt, pepper, and vinegar,” he noted.

The suspension of New York’s legislature, Dickinson wrote, “is a parliamentary assertion of the supreme authority of the British legislature over these colonies in the point of taxation; and it is intended to compel New York into a submission to that authority.”

“It seems therefore to me as much a violation of the liberty of the people of that province, and consequently of all these colonies, as if the Parliament had sent a number of regiments to be quartered upon them, till they should comply,” the future delegate to the Constitutional Convention concluded.

Dickinson College in Pennsylvania is named after John Dickinson. George Wilson Peale painted this portrait of him around the time of the Constitutional Convention. (click to see the whole picture)

When Parliament passed The Tea Act of 1773, which removed the British East India Company’s export tax for shipping tea to British America, but left the tax on tea imported to British North America intact, the call to arms, “No Taxation Without Representation” reverberated throughout the colonies.

Fourteen years later, after the American Revolution had been fought and won, and the Articles of Confederation had clearly failed, the delegates who gathered at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in May of 1787 knew they had to create a single, lasting, definitive document that every colony could agree to that would be the highest authority for what “the rule of law” meant in America.

And that is exactly what they produced in the Constitution that was ratified and created the United States of America in 1789.

That highest authority could be changed, but those changes–called amendments–required a much more elaborate and participative process than the mere enacting of a single statute by the new country’s legislative body.

As for the document that emerged, it set the standard for two key concepts of governance that, while present in a few other smaller countries at the time, had never been fully developed in the creation of a major nation: federalism and the separation of powers.

Once the rest of the world saw it, they took notice. Soon, other countries began to follow the example of the United States.

Not all of the governments established by those single document constitutions have fared as well as our own.

The French Constitution of 1791, ratified just two years after the formation of the new government of the United States, established a constitutional monarchy to replace the absolute monarchy of the ill-fated King Louis XVI. That agreement barely lasted a year, and was replaced by the French Constitution of 1793, which established the first of five French republics, each with its own constitution. The current French Constitution of 1958 established the Fifth French Republic.

The Polish Constitution of 1791, which established a constitutional monarchy, also lasted less then two years.

In 1814, Norway had better luck with the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway, which established a constitutional monarchy that continues to this day.

Now, in 2020, more than one hundred countries have a single written document that serves as their constitution. However, in many of those countries the document has little impact, since they lack the same tradition of and respect for “the rule of law” found in the United States and Great Britain.

In Part II of this series of articles on the three things that make the United States Constitution unique in the history of the world, we’ll talk about Federalism, and in Part III we’ll look at The Separation of Powers.

Written for and published by the Tennessee Star ~ April 10, 2017