The Second Amendment declares that individual citizens have a right to keep and bear arms.

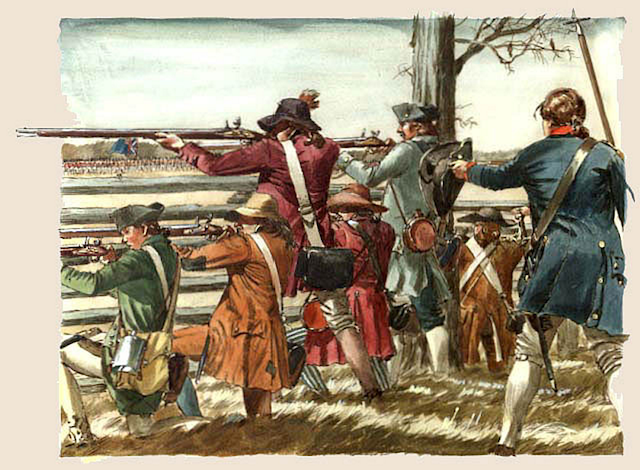

Revolutionary militia fire on the British

That right is not created by the Second Amendment but is recognized to naturally exist independent of the Constitution. The purpose of the Second Amendment is to make clear that the federal government lacks any authority to restrict or infringe that individual right.

The right is not just the right of the individual to own arms that are suitable for hunting, self defense, recreational shooting or collecting – although each of those are within its scope. The Second Amendment, much like the First Amendment, also exists to protect a political right and the political power that was essential to founding of this nation and as indicated in the Declaration of Independence.

That right is the supreme authority and the power of the citizens of any nation or government to change, abolish, redo or re-establish their government. At the time that the Second Amendment was written, its backdrop was the successful secession from Britain that costs so many lives in the Revolutionary War.

“The Death of Benjamin Rush” by Turnbull

The Founding Fathers understood that freedom and liberty demanded the overwhelming civilian ownership of arms to protect the people, the States, and the newly formed nation against another tyrannical government. This sentiment is embodied in the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

The Second Amendment and Its Creation

As stated in the Declaration of Independence, the citizens are vested with certain rights and with the right to establish governments and to grant to those governments such authority. Of equal or greater importance, the citizens have the absolute power to deny such authority to government as the citizens deem appropriate.

At the time of the Revolution, this nation was comprised of colonies which became, upon seizing independence, separate sovereign states. Founding Fathers understood that by entering into a union of States that they could collectively provide for certain desirable, mutually beneficial services such as regulation of interstate trade, a monetary system, immigration policies, management of a shared army and navy, and to provide for the defense of the nation. Therefore, for this purpose, the States designated representatives to convene and to prepare a proposed agreement that became the Constitution.

The structure of the Constitution shows that the States retained their sovereignty but that they mutually agreed to jointly delegate certain limited but commonly applicable powers to this proposed federal government.

As the draft of the Constitution was finalized at the Constitutional Convention and sent to the states for ratification, it soon became clear that some believed that the Constitution, while clearly delegating only specific powers to the proposed federal government, was lacking because it did not address the retained authority of the States in matters that were not specifically delegated to the proposed federal government. Nor did it identify any of the rights of individuals which were to remain beyond the authority of the federal government.

As the Constitution Series here has addressed, this battle between the Anti-Federalists and Federalists was resolved through the widespread acceptance of the Massachusetts Compromise–the promise by the Federalists to enact a Bill of Rights in the first Congress, a promise that was honored.

One of the ten amendments contained in the Bill of Rights that emerged from this compromise was the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, which consists of a single, imperative sentence:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

The Second Amendment was approved by Congress on September 25, 1789, as one of the ten initial proposed amendments to the Constitution. Once approved by Congress, the amendments had to be ratified, or approved, by the States. It took more than two years to get enough of the States to ratify the adoption of the Bill of Rights which finally occurred on December 15, 1791.

The language of the Second Amendment has not changed in 226 years. As a constitutional matter, the amendment’s purpose and its scope have not changed during that period either.

At the time of its passage, the Second Amendment was not just a sudden idea that was scribbled down as a singular thought. Each word, each phrase, even the punctuation of the sentence was carefully considered and discussed to make clear that the federal government lacked any authority to infringe the rights of the citizens regarding the ownership and use of arms.

What was clear to the writers of the Bill of Rights in 1789–by the terms they used and the context of their writings and debates–has, most certainly, become uncertain to some, perhaps many, today.

As to this modern uncertainty, Thomas Jefferson commented regarding how the Constitution should be read:

On every question of construction let us carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted, recollect the spirit manifested in the debates, and instead of trying what meaning can be squeezed out of the text, or invented against it, conform to the probable one which was passed.

It is clear that the modern confusion over what the Second Amendment means developed long after its adoption, and can be more accurately characterized as a contrived disagreement.

It is clear that the modern confusion over what the Second Amendment means developed long after its adoption, and can be more accurately characterized as a contrived disagreement.

There really was almost no disagreement on the matter in the late 1700s following its passage, throughout most of the 1800s and even into the early 1900s.

The disagreement over its meaning became more obvious in the 1920s and 1930s and expanded rapidly during the succeeding years of massive government growth and expansion until at least 2008.

In 2008 the United States Supreme Court addressed the meaning of the Second Amendment, or parts of it, in a case called District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 128 S. Ct. 2783 (2008).

In Heller, the United States Supreme Court examined a law in the District of Columbia that banned civilian handgun possession and which required the residents to keep any lawfully owned firearms unloaded and dissembled or bound by a trigger lock or similar device. Mr. Heller was a special police officer who applied to the District of Columbia to be able to have a registered handgun in his home. The District of Columbia denied that request and the litigation resulted.

Richard Heller was a special police officer and litigant in the landmark 2008 Supreme Court Case. (Image: Matthew Worden)

One of the core issues in Heller, perhaps the core issue that Justice Antonin Scalia addressed in writing the majority opinion for 5 of the 9 justices in Heller, was whether the Second Amendment protected the right of an individual or whether that right somehow only pertained to collectives of individuals while serving in a “militia” or in other organized government service.

The question before the Court was whether the District of Columbia’s laws violated the rights of individuals who are not affiliated with any state-regulated militia, but who wish to keep handguns and other firearms in their homes for self defense and other private use. Justice Scalia concluded that “[t]here seems to us no doubt, on the basis of both text and history, that the Second Amendment conferred an individual right to keep and bear arms.” See: Heller, 554 U.S. at 595, 128 S. Ct. at 2799.

That single sentence triggered more repercussions when it was written in 2008 than did the writing of the Second Amendment itself in 1789. The Court’s conclusion that the Second Amendment protected the rights of individuals to purchase, own and possess firearms resolved, for now, the misplaced “collective rights” assertions that some government agencies had relied upon over the last century to impose numerous firearms bans and prohibitions and rendered perhaps many of those bans unconstitutional.

Antonin Scalia was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986, and served after his confirmation that same year until his death in 2016.

Another critical concept addressed by Justice Scalia was the source of the right. Some today talk about their “Second Amendment Right” as if the Second Amendment is the source of that right.

It is not. Justice Scalia was cautious to point out that neither the Constitution nor the Bill of Rights created individual rights. Indeed, if the right was created by the Constitution or the Bill of Rights, it could be eliminated by amending those documents. Thus, Justice Scalia wrote: “Putting all of these textual elements together, we find that they guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.”

This meaning is strongly confirmed by the historical background of the Second Amendment.

We look to this because it has always been widely understood that the Second Amendment, like the First and Fourth Amendments, codified a pre-existing right. The very text of the Second Amendment implicitly recognizes the pre-existence of the right and declares only that it “shall not be infringed.”

As we said in United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 553, 23 L.Ed. 588 (1876), “[t]his is not a right granted by the Constitution. Neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The second amendment declares that it shall not be infringed….” See: Heller, 554 U.S. at 592, 128 S. Ct. at 2797-98.

Justice Scalia wrote extensively about the circumstances and time that gave rise to the Bill of Rights, the discussions surrounding the drafting of the Bill of Rights and how legislators, courts and even scholars addressed the Second Amendment from its creation and through the late 1800s.

Justice Scalia wrote extensively about the circumstances and time that gave rise to the Bill of Rights, the discussions surrounding the drafting of the Bill of Rights and how legislators, courts and even scholars addressed the Second Amendment from its creation and through the late 1800s.

According to the Court, the primary purpose of the Amendment is found in the phrase “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” In an analysis spanning approximately 8 pages, Justice Scalia observed that the phrase “the people” also exists in other six other locations in the Constitution, such as the First Amendment. Justice Scalia noted “in all six other provisions of the Constitution that mention “the people,” the term unambiguously refers to all members of the political community, not an unspecified subset.”

As used in the Constitution, therefore, the term “the people” refers to all citizens although there are some very narrow exceptions. It certainly did not mean only those individuals who were in or while acting subject to a specific collective activity such as government employees, those in the formal military or those engaged in militia service.

Similarly, Justice Scalia noted that the phrase “keep and bear arms” meant to have weapons and carry them. The majority opinion did not limit that phrase to only permitting the bearing of arms as part of military or militia service. The phrase applies to any lawful use and possession including matters such as self-defense, hunting and recreational uses.

The majority opinion also explored the topic of what weapons are included within the scope of the word “arms.” Although the Court did not exhaustively answer that question, it easily found that handguns and longarms that were commonly owned by the people across the nation are within the scope of the term “arms” and thus constitutionally protected to civilian ownership.

The Court rejected the argument that the term “arms” was limited to those weapons in existence in the late 1700s. Justice Scalia wrote:

Some have made the argument, bordering on the frivolous, that only those arms in existence in the 18th century are protected by the Second Amendment. We do not interpret constitutional rights that way. Just as the First Amendment protects modern forms of communications, … and the Fourth Amendment applies to modern forms of search … the Second Amendment extends, prima facie, to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not in existence at the time of the founding. Heller, 554 U.S. at 582, 128 S. Ct. at 2791-92.

But the question still exists as to whether the term “arms” includes just the normal arms that might be used by an individual for self-defense or hunting or does it include military grade weaponry. In Tennessee and many state, for example, it is legal for civilians to own fully automatic machine guns so long as they pay a federal transfer tax when they purchase the weapon.

But the question still exists as to whether the term “arms” includes just the normal arms that might be used by an individual for self-defense or hunting or does it include military grade weaponry. In Tennessee and many state, for example, it is legal for civilians to own fully automatic machine guns so long as they pay a federal transfer tax when they purchase the weapon.

The Tennessee Supreme Court has twice addressed the question regarding what are “arms” under the Constitution and it did so, at the time, also with reference to Article I, Section 26 of the Tennessee Constitution. Under both constitutional provisions, the Tennessee Court found that the constitutional protection of arms included such weapons as would be appropriate for a solider to carry in a modern war.

As we understand the able opinion of Judge Green, in the case of Aymette v. State, 2 Hum., 158, he holds the same general views on this question, which are to be found in this opinion.

He says:

“As the object for which the right to keep and bear arms is secured is of a general nature, to be exercised by the people in a body for their common defense, so the arms–the right to keep which is secured–are such as are usually employed in civilized warfare, and constitute the ordinary military equipment. If the citizens have these arms in their hands, they are prepared in the best possible manner, to repel any encroachments upon their rights by those in authority.” Andrews v. State, 50 Tenn. 165, 184-85 (1871).

Note the references to weapons normally used in “civilized warfare” and that are the “ordinary military equipment” of the modern soldier. That definition likely includes weapons other than deer rifles and your personal defense handguns.

Similarly, the understanding that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to own weapons suitable for use by modern soldier is summarized and acknowledged by the United States Justice Department in a brief that it filed with the United States Supreme Court in U.S. v. Miller in 1939:

The Second Amendment does not confer upon the people the right to keep and bear arms; it is one of the provisions of the Constitution which, recognizing the prior existence of a certain right, declares that it shall not be infringed by Congress. Thus the right to keep and bear arms is not a right granted by the Constitution and therefore [it] is not dependent upon that instrument for its source. United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 543; Presser v. Illinois, 116 U. S. 252, 265; Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U. S. 275, 281.

While some courts have said that the right to bear arms includes the right of the individual to have them for the protection of his person and property as well as the right of the people to bear them collectively (People v. Brown, 253 Mich. 537; State v. Duke, 42 Tex. 455), the cases are unanimous in holding that the term “arms” as used in constitutional provisions refers only to those weapons which are ordinarily used for military or public defense purposes and does not relate to those weapons which are commonly used by criminals.

But what about the “militia” cause?

Militia 1812

The disagreement over whether the Second Amendment protected a right vested in individuals or whether it was a collective right that could only be exercised by groups of individuals engaged in some military service was one of the main points addressed in the individual rights analysis in Heller.

According to Scalia’s analysis, the phrase a “well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State” did not mean that the right to arms only existed while engaged in military or militia service. To the contrary, this introductory clause underscored the belief, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence and that was widely held at the time that the Constitution was written, that a well armed and trained, i.e., “regulated,” citizenry was necessary to protect the nation from invasions as well as to protect the nation from tyrants that might overtake the nation.

This did not come, in the minds of the Founders, from organized military training but from the citizens having the right and possession of all manner of firearms suitable for use by a soldier so that the citizens could be familiar with the weapons if and when called upon for their service.

Early courts easily understood that the arms referenced in the Second Amendment included arms suitable to a soldier when called into public or military service.

In part, this was because at the time of our founding and through most of our history, our constitutions and laws have recognized the existence of the “unorganized militia” which is a term that refers generally to all citizens within the ages of approximately 18 and 45 but which applies to any citizen who will voluntarily serve if needed.

Thus the individual citizens in Tennessee and many other states, whether they realize it or not, are by law the “militia.” Tennessee statutes, for example, state Tenn. Code Ann. § 58-1-104 (d)

The militia shall consist of all able-bodied male citizens who are residents of this state and between eighteen (18) and forty-five (45) years of age and who are not members of the army or navy as hereinabove defined, and who may not otherwise be exempted by the laws of this state or the United States.

Although any individual can respond to a militia call, any individual who is within the statutory age range of the militia but who fails to respond when called out by the Tennessee governor for service “shall be considered as a deserter and treated accordingly.” Tenn. Code Ann. §58-1-302. Thus, individuals who fall within the age range specified but who do not properly respond to service when called are subject to criminal charges – today. Whether it is likely that the individuals of this state will be called into service is immaterial. The fact is that these individuals are subject to a compulsory call to militia service.

But for what purpose can the citizens of the state be called into militia service? The Tennessee constitution provides in Article III, Section 5, that they citizens can be called into service by the governor only “in case of rebellion or invasion …” Therefore, a call cannot be made merely for an emergency such as a flood, tornado or fire. The governor can only call the citizens into militia service for what would be service in combat or defense.

But for what purpose can the citizens of the state be called into militia service? The Tennessee constitution provides in Article III, Section 5, that they citizens can be called into service by the governor only “in case of rebellion or invasion …” Therefore, a call cannot be made merely for an emergency such as a flood, tornado or fire. The governor can only call the citizens into militia service for what would be service in combat or defense.

The importance of a trained citizenry that was familiar and capable with military arms was also recognized by the United States government. For example, in 1903 the government created the Department of Civilian Marksmanship. The program was formed by Congress at a time when civilian use and marksmanship of firearms was deemed essential to the nation’s military preparedness.

Under this program, national marksmanship competitions are held involving civilians firing military weapons. In addition, the program has for now more than 110 years sold to individual citizens and shipped directly to their homes military weapons including the M1 Garand, the 1903 Enfield, and the M1 carbine.

It is this individual duty of the citizens which underscored the necessity that they be familiar with and own arms – arms suitable for such service. This duty is one of the reasons that the Second Amendment contains the militia clause as written and today.

Heller only addressed a narrow range of questions. There are many important issues that are yet to be addressed in either the legislatures or the courts.

For example, Justice Scalia did note that the existence of the right, while protected, did not mean that the right could not be lost, such as by criminal convictions, or that the right could not be regulated to some extent. He did not need to and did not address the scope of such restrictions other than to say that the restrictions by the District of Columbia were unconstitutional.

This is the seventh of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series.

Written by John Harris for The Tennessee Star ~ May 15, 2017