The scars left by civil war soon heal and fade away, as does the memory of the privations and sufferings which it entailed. The angry controversies which precede and the bitterness which follows pass away with the generation whose quarrels necessitated the stern arbitrament of war. New generations of people of the same blood come together as companions in the same walks of life, and join together in the same aims, aspirations, and ambitions, forgetful or regardless of the quarrel which divided their fathers, the causes for which have passed into history.

In our own country the time has arrived when the hateful memories of the war can no longer be evoked to excite political prejudice or passion. The survivors, old soldiers on either side, fraternize together on all occasions and “fight their battles o’er again” with mutual pride in the valor of their countrymen. They lend assistance to deck the graves of their departed antagonists, and aid each other in honoring the memory of their dead. In the meanwhile a new generation has grown to manhood, who believe that these events belong to history and have no part to play in the active business or politics of the present hour.

I am not here to enter into a discussion of the causes of the war, or upon a vindication of those whose statesmanship or want of statesmanship brought it about. The Confederate soldiers had little to do with the causes of the war, and few of them shared in the political controversies which preceded it.

An angry and excited presidential election, in which a great number of them were not voters; the triumph of a sectional candidate, who carried all of the Northern States and who did not have an electoral ticket or receive a vote in the South; a profound alarm and feeling of apprehension for the future of the country, which prevailed throughout the South, and was shared by the most conservative and Union-loving men of that section ; while those of the more extreme views, perhaps a majority, considered that the only safety for the South, its liberties and institutions, could be found in immediate separation from the Union; a short, hurried and impassioned canvass before the people, the issue being narrowed down to immediate secession or co-operation; the election of conventions ; the adoption of ordinances of secession; the solemn withdrawal of Senators and Representatives from Congress, following the action of their States; the seizure of the forts and arsenals of the national government; the formation of a provisional government; the firing on Sumter; the call to arms, North and South — all of these strange things passed with the rapidity of a dream, and it seems like a dream as we look back upon them after the lapse of twenty-five years.

An angry and excited presidential election, in which a great number of them were not voters; the triumph of a sectional candidate, who carried all of the Northern States and who did not have an electoral ticket or receive a vote in the South; a profound alarm and feeling of apprehension for the future of the country, which prevailed throughout the South, and was shared by the most conservative and Union-loving men of that section ; while those of the more extreme views, perhaps a majority, considered that the only safety for the South, its liberties and institutions, could be found in immediate separation from the Union; a short, hurried and impassioned canvass before the people, the issue being narrowed down to immediate secession or co-operation; the election of conventions ; the adoption of ordinances of secession; the solemn withdrawal of Senators and Representatives from Congress, following the action of their States; the seizure of the forts and arsenals of the national government; the formation of a provisional government; the firing on Sumter; the call to arms, North and South — all of these strange things passed with the rapidity of a dream, and it seems like a dream as we look back upon them after the lapse of twenty-five years.

And so went forth the Southern youth to battle, full of hope, inspired with confidence, thinking to return conqueror after a war of ninety days. What knew he, or cared he, for the causes of the war? His country was imperiled, his State was in danger of invasion, an enemy was advancing upon his home, and it was his duty to meet and assist in driving back the invader.

“Theirs not to reason why

Theirs but to do and die.”

And the ninety summer days were lengthened into four years. And the glamour of war was gone, and all of its romance; and, in exchange, its bitter, stern realities — the long campaigns, the bloody, indecisive battles, the forced marches, the summer’s heat, the winter’s cold, the privations, the wounds, the sickness, the prison, the retreat, the defeat, the loss of hope. Ah, the sufferings and ills which these men bore bravely during those four long years! And as their columns wasted from the ravages of disease and death they were recruited from home, until nearly all except the occupants of the cradle and the grave had gone to the front. And then the war ended, and the survivors turned their steps homeward, ragged, wounded, maimed, gaunt, hungry, and hopeless.

Marietta, Georgia

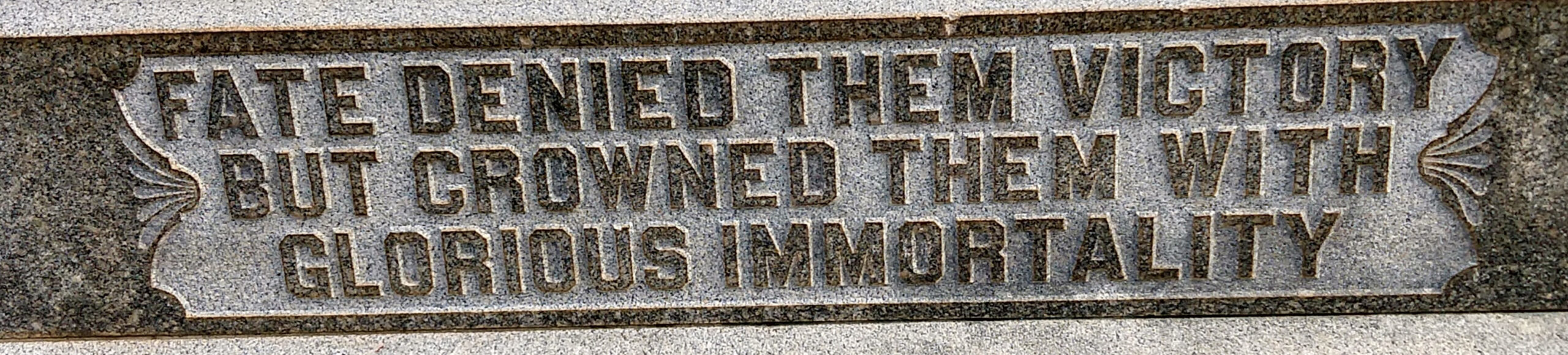

In memory I see again these regiments and battalions starting for the front, with music and banners and all the panoply of war; and memory brings back to me, and to all of you, the recollection of loved faces and brave hearts of many who were marching in the ranks, and who are absent from our gathering to-day, who will respond to life’s roll call no more forever. We cannot strew flowers upon their scattered graves; we cannot mark their unknown resting-places with stone or monument ; we cannot gather their earthly spoil into beautiful mausoleums or cities of the dead; but we erect this monument in their honor that all people in all time to come may know that the soldiers who died for the Confederate cause are not without love and honor and reverence in the land which gave them birth:

”Rest on, embalmed and sainted dead,

Dear as the blood ye gave,

No impious footstep here shall tread

The herbage of your grave;

Nor shall your glory be forgot

While Fame her record keeps,

Or Honor points the hallowed spot

Where Valor proudly sleeps.

“Yon marble minstrel’s voiceless stone,

In deathless song shall tell,

When many a vanished age hath flown,

The story how ye fell;

Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter’s blight,

Nor Time’s remorseless doom,

Shall dim one ray of glory’s light,

That gilds your deathless tomb.”

Benjamin Franklin Jonas, Former United States Senator from Louisiana

[Extracts from an address at the laying of the corner stone of a monument to the memory of the Confederate dead, at Baton Rouge, La., February 22, 1886.]

Benjamin F. Jonas

Benjamin F. Jonas. Benjamin Franklin Jonas (July 19, 1834 – December 21, 1911) was a Democratic U.S. Senator from Louisiana and an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He was the third Jew to serve in the Senate.

Published by Edwin Dubois Shurter, Oratory of the South: From the Civil War to the Present Time (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1908), 31-34.