The Alamo was a mission founded in 1718. It ceased to function as a church in 1793. At the time of the famous siege the mission chapel was a roofless ruin, but a high rock wall about three feet thick enclosed an area around the chapel large enough to accommodate 1,000 men. Within that enclosure the battle of the Alamo was fought, with a last stand in the chapel.

The Alamo was a mission founded in 1718. It ceased to function as a church in 1793. At the time of the famous siege the mission chapel was a roofless ruin, but a high rock wall about three feet thick enclosed an area around the chapel large enough to accommodate 1,000 men. Within that enclosure the battle of the Alamo was fought, with a last stand in the chapel.

In 1835, during the battle for Texas Independence from Mexico, the Texans had captured San Antonio. Only 144 soldiers, most of them volunteers, were left to guard the city. They were under the command of Lt. Colonel W. B. Travis. On February 22, 1836 a Mexican force of almost 5,000 troops under Santa Anna arrived at San Antonio. Travis and Colonel James Bowie (another great Southerner who gave us the Bowie knife) believed that the Alamo must be held to prevent Santa Anna’s march into the interior. On February 23, they and their forces went into the fort and prepared to withstand attack by the Mexicans.

One of the most gallant stands of courage and undying self-sacrifice, which have come down through the pages of history is the defense of the Alamo, which is one of the priceless heritages of Texans. It was the battle-cry of “Remember the Alamo” that later spurred on the forces of Sam Houston at San Jacinto. Anyone who has ever heard of the brave fight of Colonel Travis and his men is sure to “Remember the Alamo.“

Generalisimo Santa Anna

Besieged by Santa Anna, who had reached Bexar on February 23, Colonel William Barret Travis, with his force of 182, refused to surrender but elected to fight and die, which was almost certain, for what they thought was right. The position of these men was known but no aid reached them. The request to Colonel James W. Fannin for assistance had gone unheeded. No relief was in store. As the Battle of the Alamo was in progress, a part of the Texas Army had assembled in Gonzales under the command of Mosely Baker in the latter part of February. From this army, a gallant band of 32 courageous men under the command of Albert Martin left to join the garrison at the Alamo. Making their way through the enemy lines, these 32 men joined the doomed defenders and perished with them.

On March 2, during the siege of the Alamo, Texas independence was declared. Four days later, the document was signed with the blood shed at the Alamo. It was under such conditions that Travis and his men fought off the much larger force under Santa Anna. It was with the love of liberty in his voice and the courage of the faithful and brave that Travis gave his men the none too cheerful choice of the manner in which they wished to die.

Realizing that no help could be expected from the outside and that Santa Anna would soon take the Alamo, Travis addressed his men, told them that they were fated to die for the cause of liberty and the freedom of Texas. Their only choice was in which way they would make the sacrifice. He outlined three procedures to them: first, rush the enemy, killing a few but being slaughtered themselves in the hand-to-hand fight by the overpowering Mexican force; second, to surrender, which would eventually result in their massacre by the Mexicans, or, third, to remain in the Alamo and defend it until the last man, thus giving the Texas army more time to form and likewise taking a greater toll among the Mexicans.

Realizing that no help could be expected from the outside and that Santa Anna would soon take the Alamo, Travis addressed his men, told them that they were fated to die for the cause of liberty and the freedom of Texas. Their only choice was in which way they would make the sacrifice. He outlined three procedures to them: first, rush the enemy, killing a few but being slaughtered themselves in the hand-to-hand fight by the overpowering Mexican force; second, to surrender, which would eventually result in their massacre by the Mexicans, or, third, to remain in the Alamo and defend it until the last man, thus giving the Texas army more time to form and likewise taking a greater toll among the Mexicans.

The third choice was the one taken by the men. Their fate was death and they faced it bravely, asking no quarter and giving none. The siege of the Alamo ended on the dawn of March 6, when its gallant defenders were put to the sword. But it was not an idle sacrifice that men like Travis and Davy Crockett and James Bowie made at the Alamo. It was a sacrifice upon the altar of liberty.

This is their story – and in many ways – America’s story.

The siege and the final assault on the Alamo in 1836 constitute the most celebrated military engagement in Texas history. The battle was conspicuous for the large number of illustrious personalities among its combatants. These included Tennessee congressman David Crockett, entrepreneur-adventurer James Bowie, and Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna. Although not nationally famous at the time, William Barret Travis achieved lasting distinction as commander at the Alamo. For many Americans and most Texans, the battle has become a symbol of patriotic sacrifice. Traditional popular depictions, including novels, stage plays, and motion pictures, emphasize legendary aspects that often obscure the historical event.

The siege and the final assault on the Alamo in 1836 constitute the most celebrated military engagement in Texas history. The battle was conspicuous for the large number of illustrious personalities among its combatants. These included Tennessee congressman David Crockett, entrepreneur-adventurer James Bowie, and Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna. Although not nationally famous at the time, William Barret Travis achieved lasting distinction as commander at the Alamo. For many Americans and most Texans, the battle has become a symbol of patriotic sacrifice. Traditional popular depictions, including novels, stage plays, and motion pictures, emphasize legendary aspects that often obscure the historical event.

To understand the real battle, one must appreciate its strategic context in the Texas Revolution. In December 1835 a Federalist army of Texan (or Texian, as they were called) immigrants, American volunteers, and their Tejano allies had captured the town from a Centralist force during the siege of Bexar. With that victory, a majority of the Texan volunteers of the “Army of the People” left service and returned to their families. Nevertheless, many officials of the provisional government feared the Centralists would mount a spring offensive. Two main roads led into Texas from the Mexican interior. The first was the Atascosito Road, which stretched from Matamoros on the Rio Grande northward through San Patricio, Goliad, Victoria, and finally into the heart of Austin’s colony. The second was the Old San Antonio Road, a camino real that crossed the Rio Grande at Paso de Francia (the San Antonio Crossing) and wound northeastward through San Antonio de Béxar, Bastrop, Nacogdoches, San Augustine, and across the Sabine River into Louisiana.

Two forts blocked these approaches into Texas: Presidio La Bahía (Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio) at Goliad and the Alamo at San Antonio. Each installation functioned as a frontier picket guard, ready to alert the Texas settlements of an enemy advance. James Clinton Neill received command of the Bexar garrison. Some ninety miles to the southeast, James Walker Fannin, Jr., subsequently took command at Goliad. Most Texan settlers had returned to the comforts of home and hearth. Consequently, newly arrived American volunteers-some of whom counted their time in Texas by the week-constituted a majority of the troops at Goliad and Bexar. Both Neill and Fannin determined to stall the Centralists on the frontier. Still, they labored under no delusions. Without speedy reinforcements, neither the Alamo nor Presidio La Bahía could long withstand a siege.

At Bexar were some twenty-one artillery pieces of various calibers. Because of his artillery experience and his regular army commission, Neill was a logical choice to command. Throughout January he did his best to fortify the mission fort on the outskirts of town. Maj. Green B. Jameson, chief engineer at the Alamo, installed most of the cannons on the walls. Jameson boasted to Gen. Sam Houston; that if the Centralists stormed the Alamo, the defenders could “whip 10 to 1 with our artillery.” Such predictions proved excessively optimistic. Far from the bulk of Texas settlements, the Bexar garrison suffered from a lack of even basic provender.

On January 17, Sam Houston, the commander of the revolutionary troops, sent Colonel Jim Bowie and 25 men to San Antonio with orders to destroy the Alamo fortifications and retire eastward with the artillery. But Bowie and Neill agreed that it would be impossible to remove the 24 captured cannons without oxen, mules or horses. And they deemed it foolhardy to abandon that much firepower – by far the most concentrated at any location during the Texas Revolution. Bowie also had a keen eye for logistics, terrain, and avenues of assault. Knowing that General Houston needed time to raise a sizable army to repel Santa Anna, Bowie set about reinforcing the Alamo after Neill was forced to leave because of sickness in his family.

On January 17, Sam Houston, the commander of the revolutionary troops, sent Colonel Jim Bowie and 25 men to San Antonio with orders to destroy the Alamo fortifications and retire eastward with the artillery. But Bowie and Neill agreed that it would be impossible to remove the 24 captured cannons without oxen, mules or horses. And they deemed it foolhardy to abandon that much firepower – by far the most concentrated at any location during the Texas Revolution. Bowie also had a keen eye for logistics, terrain, and avenues of assault. Knowing that General Houston needed time to raise a sizable army to repel Santa Anna, Bowie set about reinforcing the Alamo after Neill was forced to leave because of sickness in his family.

Houston may have wanted to raze the Alamo, but he was clearly requesting Smith’s consent. Ultimately, Smith did not “think well of it” and refused to authorize Houston’ s proposal.

Travis and Bowie understood that the Alamo could not hold without additional forces. Their fate now rested with the General Council in San Felipe, Fannin at Goliad, and other Texan volunteers who might rush to assist the beleaguered Bexar garrison.

Santa Anna sent a courier to demand that the Alamo surrender. Travis replied with a cannonball. There could be no mistaking such a concise response. Centralist artillerymen set about knocking down the walls. Once the heavy pounding reduced the walls, the garrison would have to surrender in the face of overwhelming odds. Bottled up inside the fort, the Texans had only one hope-that reinforcements would break the siege.

Travis was on recruiting duty for the newly created Texas regular army when he was ordered to take what men he had to reinforcement the Alamo. He only had 40, and nine deserted in route, taking supplies he had bought with his own money.

He unexpectedly became commander of the Alamo, Jim Bowie having succumbed to typhoid fever – and found himself holding off the bulk of the Mexican army. His appeals for aid showed he understood the situation perfectly – but he also kept announcing he would hold out no matter what, even unto death.

He did.

Remarkably, Travis was able to see beyond his own dire predicament to the big picture. Even more remarkably, he was able to persuade and convince in excess of 180 men to share his vision. Possibly, because of Travis’ decisive action and personal courage, history took a different course.

Those who believe that historical forces rather than individuals control events should consider the actions of William Travis. Clearly, his decision to sacrifice himself at the Alamo is one of the most decisive contributions by a single individual in recent world history.

March 2: Texas Independence is declared at Washington-on-the-Brazos and on that day Sam Houston issues a broadside:

War is raging on the frontiers. Bejar is besieged by two thousand of the enemy, under the command of general Siezma. Reinforcements are on their march, to unite with the besieging army. By the last report, our force in Bejar was only one hundred and fifty men strong. The citizens of Texas must rally to the aid of our army, or it will perish. Let the citizens of the East march to the combat. The enemy must be driven from our soil, or desolution will accompany their march upon us. Independence is declared, it must be maintained. Immediate action, united with valor, alone can achieve the great work. The services of all are forthwith required in the field.

Sam Houston,

Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

P.S. It is rumored that the enemy are on their march to Gonzales, and that they have entered the colonies. The fate of Bejar is unknown. The country must and shall be defended. The patriots of Texas are appealed to, in behalf of their bleeding country. – S.H.

At 4 o’clock on the morning of March 6, Santa Anna advanced his men to within 200 yards of the Alamo’s walls. Just as dawn was breaking, the Mexican bloodcurdling bugle call of the Deguello echoed the meaning of the scarlet flag above San Fernando: no quarter. It was Captain Juan Seguin’s Tejanos, the native-born Mexicans fighting in the Texan army, who interpreted the chilling music for the other defenders.

Santa Anna hurled his columns at the battered walls from four directions. Texan gunners stood by their artillery. As about 1,800 assault troops advanced into range, canister ripped through their ranks. Staggered by the concentrated cannon and rifle fire, the Mexican soldiers halted, reformed, and drove forward. Soon they were past the defensive perimeter. Travis, among the first to die, fell on the north bastion. Abandoning the walls, defenders withdrew to the dim rooms of the Long Barracks. There, some of the bloodiest hand-to-hand fighting occurred.

Santa Anna’s first charge was repulsed, as was the second, by the deadly fire of Travis’ artillery. At the third charge, one Mexican column attacked near a breach in the north wall, another in the area of the chapel, and a third, the Toluca Battalion, commenced to scale the walls. All suffered severely. Out of 800 men in the Toluca Battalion, only 130 were left alive. Fighting was hand-to-hand with knives, pistols, clubbed rifles, lances, pikes, knees and fists. The dead lay everywhere. Blood spilled in the convent, the barracks, the entrance to the church, and finally in the rubble-strewn church interior itself. Ninety minutes after it began, it was over.

Bowie, too ravaged by illness to rise from his bed, found no pity. The chapel fell last. By dawn the Centralists had carried the works. The assault had lasted no more than ninety minutes. As many as seven defenders survived the battle, but Santa Anna ordered their summary execution. By eight o’clock every Alamo fighting man lay dead. Currently, 189 defenders appear on the official list, but ongoing research may increase the final tally.

All the Texians died. Santa Anna’s loss was 1,544 men. More than 500 Mexicans lay wounded, their groans mingling with the haunting strains of the distant bugle calls. Santa Anna airily dismissed the Alamo conquest as “a small affair,” but one of his officers commented, “Another such victory will ruin us.”

Although the fact remains that no one knows why some 188 men chose to die on the plains of Texas in a ruined Spanish mission that required at least 1,200 men to adequately defend all its acreage, their sacrifice brought Texas independence, which paved the way for expansion to the Pacific and added more than a million square miles to the American nation at that time. And because of their sacrifice, the Alamo is now a shrine respected and revered throughout the world. “Remember the Alamo” became the battle cry that broke Santa Anna’s back.

It is said that Davy Crockett killed more Mexicans with the butt of his rifle, after running out of ammunition, than when he was firing.

Though Santa Anna had his victory, the common soldiers paid the price as his officers had anticipated. What of real military value did the defenders’ heroic stand accomplish? The defenders of the Alamo willingly placed themselves in harm’s way to protect their country. Death was a risk they accepted, but it was never their aim.

Though Santa Anna had his victory, the common soldiers paid the price as his officers had anticipated. What of real military value did the defenders’ heroic stand accomplish? The defenders of the Alamo willingly placed themselves in harm’s way to protect their country. Death was a risk they accepted, but it was never their aim.

Even stripped of chauvinistic exaggeration, however, the battle of the Alamo remains an inspiring moment in Texas history. The sacrifice of Travis and his command animated the rest of Texas and kindled a righteous wrath that swept the Mexicans off the field at San Jacinto. Since 1836, Americans on battlefields over the globe have responded to the exhortation, “”Remember the Alamo!“

“Citizens, the feeling inspired by events within these consecrated walls, of so recent date fills my bosom with emotions. This sacred spot, and those crumbling remains, the desecrated temple of Texian liberty will teach a lesson which freeman can never forget. And, while we mourn the unhappy fate of Travis, Crockett, Bowie, and their brave compatriots let it be the boast of Texians that though Thermopylae had her messenger of defeat, the Alamo had none.” – Edward Burleson, April 2, 1842

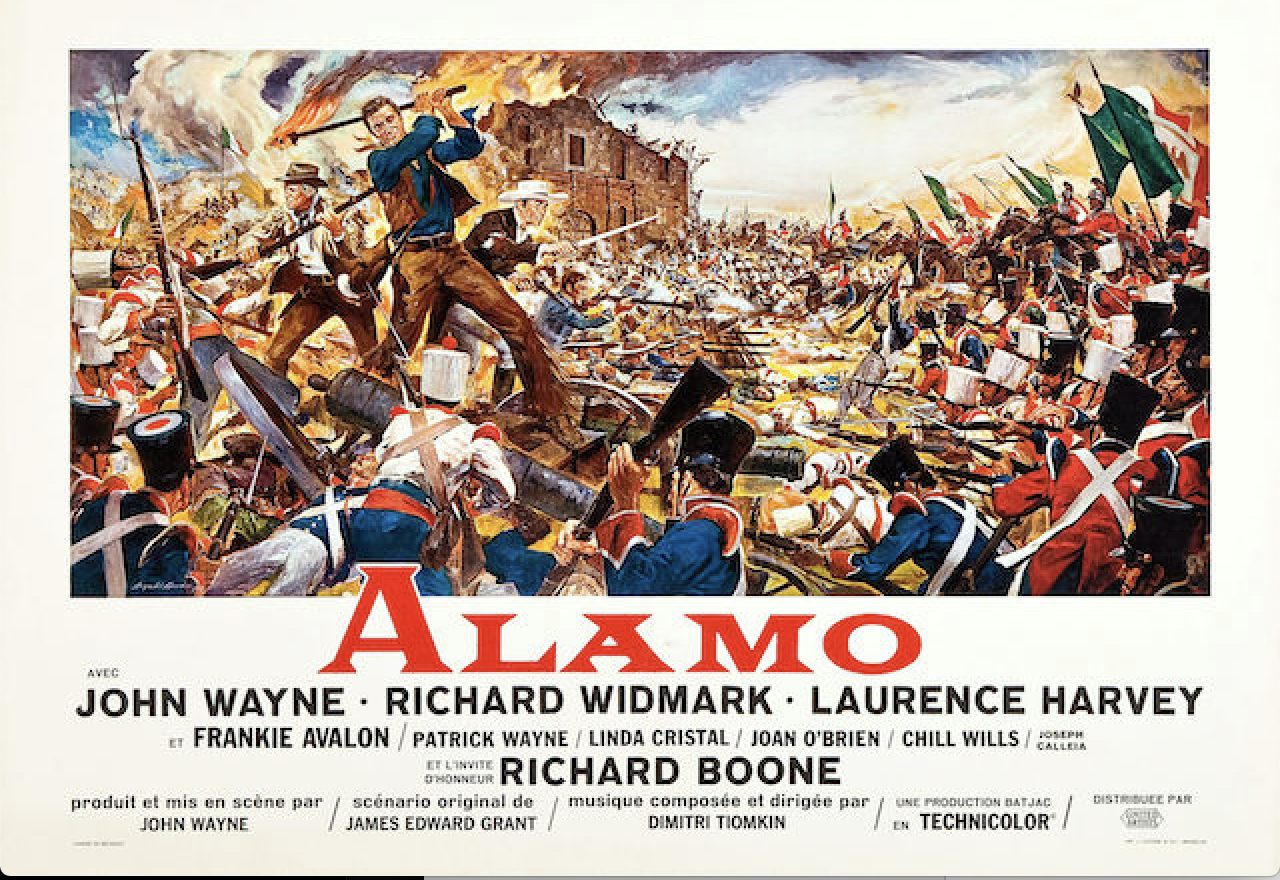

American frontiersmen – including some of their most colorful leaders – gather to support a revolution against a foreign despot, and hold out against massive odds. Until the climactic moment when they’re annihilated, taking large numbers of the enemy with them. Their sacrifice changes history.

There’s one thing wrong about this romantic tale, one that sets it apart from others like it ~ It did happen, as described.

~ Postlogue ~

Since then the Alamo has lodged itself deeply into the American psyche – and for reasons that have nothing to do with combative pride, jingoism, or juvenile fascination with gore. No, it has to do with the fact that we gauge our experiences against the extreme situations, not against average ones.

And the Alamo represents one such extreme. It teaches us that even if you’re surrounded, outnumbered ten to one, they’ve announced they’re taking no prisoners, and they’re pouring over the walls, within your soul you still have options. You can decide that something is worth dying for. That here is where you will stand. That here is where you will draw the line.