Up until a year ago, Federal Observer had a category named, Sunset Boulevard, which was used for columns dealing with film, or the lessons which film taught us on life. The following is the first post in this year that I felt was worth publishing – for numerous reasons – the historical accuracy that was depicted. Right or wrong, Left or Right, North or South…. this is not what matters here. The lessons here belong to Mr. Adair. ~ Ed.

On Sunday and on July 24 (2019), Turner Classic Movies and Fathom Events are presenting big-screen showings in theaters nationwide of “Glory,” in honor of the 30-year anniversary of its release. The greatest movie ever made about the American Civil War, “Glory” was the first and, with the exception of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” the only film that eschewed romanticism to reveal what the war was really about.

On Sunday and on July 24 (2019), Turner Classic Movies and Fathom Events are presenting big-screen showings in theaters nationwide of “Glory,” in honor of the 30-year anniversary of its release. The greatest movie ever made about the American Civil War, “Glory” was the first and, with the exception of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” the only film that eschewed romanticism to reveal what the war was really about.

The story is told through the eyes of one of the first regiments of African American soldiers. Almost from the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, S.C., the issue of black soldiers in the Union army was hotly debated. On Jan. 1, 1863, as the country faced the third year of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, rapidly accelerating the process of putting black men into federal blue.

During the war, governors were empowered to raise regiments for federal service. On Jan. 26, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton issued an order giving Massachusetts Gov. John Albion Andrew the authority “to raise such numbers of volunteers, companies of artillery for duty in the forts of Massachusetts and elsewhere, and such corps of infantry for the volunteer military service as he may find convenient, such volunteers to be enlisted for three years, or until sooner discharged, and may include persons of African descent.”

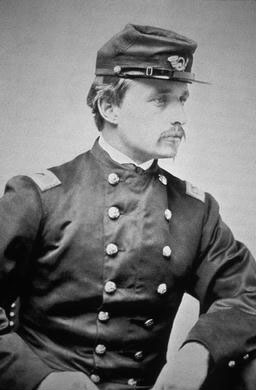

Four days later, Andrew wrote to his old friend, Francis George Shaw, asking him to speak to his son, then-Capt. Robert Gould Shaw, about accepting command of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first regiment of black soldiers to be assembled in the North. Shaw’s father traveled to Stafford County Courthouse in Virginia, where Robert was serving in the Second Massachusetts. Shaw, 25 years old, accepted the command and the rank of colonel, which went with it.

Around mid-February, the following ad appeared in Boston newspapers: “To Colored Men; Wanted Good Men for the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers of African Descent, Col. Robert G. Shaw (Commanding). $100 Bounty at expiration of term of service. Pay $13 per month and State aid for families.” (The $13 monthly pay turned out to be a lie; black troops were actually given just $10 a month. Eventually, the pay was restored to $13, but not before many of them had died in combat earning it.)

Similar recruiting posters appeared in other cities. Frederick Douglass rallied to the cause in his newspaper with a headline none could ignore: “Men of Color to Arms!” He noted, “When the first rebel cannon shattered the walls of Sumter and drove away its starving garrison, I predicted that the war then and there inaugurated would not be fought out entirely by white men.” Douglass’ words cut through the storm of rhetoric about the cause of the war: “A war undertaken and brazenly carried on for the perpetual enslavement of colored men calls logically and loudly for colored men to help suppress it.”

The response was overwhelming. Hundreds of recruits from 22 states, the District of Columbia, Nova Scotia and the West Indies swarmed into Camp Meigs, the regimental base near Boston. Among them were Douglass’ own son, 22-year-old Lewis. Toussaint L’Ouverture Delaney, 17, came from Canada; his father, Martin R. Delaney, a physician and novelist, would become the first black officer commissioned in the Union army. The officers, handpicked from prominent abolitionist families, included Garth Wilkinson James, younger brother of William and Henry James.

Most of the regiment were free men, with a sprinkling of escaped slaves. Nearly 75% were laborers or farmers. Their officers thought that their educational level was higher than that of the average regiment in the Union army; one remarked that there was “less drunkenness in this regiment” than in others he had seen.

Col. Francis George Shaw

On May 28, Shaw and the men of the 54th marched down Beacon Street in Boston. Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recorded the moment in his diary as “[a]n imposing sight, with something wild and strange about it, like a dream. At last the North consents to let the Negro fight for freedom.” At the head of the regiment were four banners: a U.S. flag, the Massachusetts state flag, and another of white silk, with a figure representing the goddess of liberty and the motto “Liberty, Loyalty, and Unity.” There was also a blue flag with a white cross and a Latin inscription: “In Hoc Signo Vinces”—With This Sign Thou Shalt Conquer.”

Five days after leaving Boston, the transport ship De Molay slipped quietly by Fort Sumter and carried the men of the 54th into the war. After several frustrating weeks of guard duty and manual labor, they saw their first combat when three companies of the 54th helped save the 10th Connecticut Infantry from disaster after a Confederate charge. “They showed no sign of fear, but fought as if they were very angry and determined to have revenge,” a Boston reporter wrote. A soldier of the 10th Connecticut wrote home that the men of the 54th “fought like heroes.”

Two days later, Shaw volunteered his regiment to lead the assault on Fort Wagner, or Battery Wagner, as it was often called. Wagner was described by historian Peter Burchard as “[a] gigantic earthwork, perhaps the strongest ever built. Its position was formidable. It stretched from the Atlantic on the east to the marshes of deep, meandering Vincent’s Creek on the west, and could only be approached by direct assault along a spit of sand, narrow even at the low tide.”

Union commanders vastly overrated the effect of land and sea bombardment on the fort. (Confederate gunners buried their guns in sandbags to protect them.) They also badly underestimated Wagner’s garrison, thinking there were perhaps 300 men behind the walls—they were wrong by nearly 1,400.

Shaw had premonitions of death. Shortly before the assault, a friend asked him why he was so sad. “If I could only live a few weeks longer with my wife, and be home a little while, I think I might die happy, but it cannot be. I do not believe I will live through our next fight.” But on the day of the assault, July 18, the same friend recalled that “[h]e seemed happy and cheerful. All of the sadness had left him, and I am sure he felt ready to meet his fate.”

The day of the battle, the men of the 54th joined in song, “When This Cruel War Is Over.” More than 600 of them (with perhaps a quarter or more of the regiment back at camp, wounded or sick) marched into position. Soldiers in white regiments yelled out words of encouragement, “Hoorah, boys! You saved the 10th Connecticut!” and “Well done! We heard your guns!” Shaw called out to his men, “The eyes of thousands will look upon what you do tonight.” He had no idea.

At 7:45 p.m., Shaw ordered, “Move in quick time until within a hundred yards of the fort. Then double quick and charge!” All questions about where black soldiers should fight were then answered. By the time the other regiments were in position, the opportunity for victory, if it ever existed, was over. The 54th charged across the beach, in and out of ditches, past rows of wooden spikes and up the slope, their ranks bled by muskets and hand grenades every foot of the way. Shaw reached the top of the wall and yelled out, “Come, boys, come!” Then, apparently hit by a rifle shot, he fell into the fort, dead.

The 54th lost perhaps half its number, killed or captured. Overall, losses on the Union side were horrendous, with more than 1,500 casualties, most from white regiments. The Confederates suffered just 181. Battery Wagner was never taken by storm. On Dec. 7, the fort was found to be deserted and was then occupied by Union soldiers.

Historian James McPherson summed up the assault on Battery Wagner in “Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies”: “If the attack was a failure, in a more profound way it was a success of historical proportions. The unflinching behavior of the regiment in the face of an overwhelming hail of lead and iron answered the skeptics’ question, Will the Negro fight?”

Shaw was buried with his men in a field outside Fort Wagner. Company C’s Sgt. William Carney had picked up the Stars and Stripes from a fallen flag-bearer and carried it to the top, sustaining wounds in his chest, arms and legs. As he staggered back into camp after the retreat, his wounded comrades cheered him; he told them that he had done no more than his duty, and that “the dear old flag” had never touched the ground. Carney was awarded the Medal of Honor, but had to wait until 1897 to receive it, at the Memorial Day ceremony in Boston for the unveiling of a monument to Shaw and his men.

*****

“Can movies teach history?” asked McPherson. “For ‘Glory,’ the answer is yes. Not only is it the first feature film to treat the role of black soldiers in the American Civil War, but it is also one of the most powerful and historically accurate movies ever made about that war.”

The idea for the greatest Civil War film ever made came to producer Freddie Fields on a windy day in Boston, when he couldn’t get a cab to his hotel. He decided to walk, cutting across the Boston Common. About halfway, he stopped to stare at a monument he had scarcely noticed before, a bronze relief by the great New York sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, which depicted Shaw leading his black soldiers of the 54th Regiment down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863.

Fields had produced and worked on such films as “Crimes of the Heart,” “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” and “American Gigolo”; now the idea for something very different began to take shape in his head. “I knew the 125th anniversary of the war was coming up and thought right away that this would make a great movie, the unknown story finally told.”

As it turned out, the director Fields wanted for the project, Edward Zwick, also knew nothing about the subject. “In my case that was inexcusable,” Zwick said. “As a student at Harvard I must have crossed the Common and passed the monument several hundred times. I’m ashamed to confess that I had never heard of the 54th Mass until I got involved in making ‘Glory.’ ”

Neither had some of actors who emerged from “Glory” as stars. Andre Braugher, who played Thomas Searles, told me, “I had read a lot about American history and the Civil War, but I never came across anything about African American soldiers in the Civil War and the 54th Mass. When I read their story, I couldn’t wait to be in this film.”

Most of “Glory” was filmed at Sea Island, Ga., 60 miles south of Savannah, with the cooperation of the Georgia State Film Commission and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. It was the first feature film set in the Civil War to use thousands of re-enactors, nearly 6,000. Crews working with the natural resources department labored for three months to recreate Fort Wagner with 30-foot walls—or, rather, three sides of it, with the fourth side left open for cameras.

Fields was so concerned with authenticity that he invited Richard Snow, editor of American Heritage magazine at the time, to read the script and come on set to offer advice. Thirty years later, Snow recalls, “It was a great thing to be a consultant, in that you have no responsibility whatever and can quack away at your heart’s content. … But I did call for one change that I pride myself on. In the initial script, the 54th was simply hurled against Battery Wagner with no preparation, which made it seem as if Shaw’s men were deliberately being sent to be slaughtered. I protested that a Union fleet had been shelling the works for a good long time before the assault, and that the commanders truly felt that the guns had been silenced and the defenders demoralized, if not killed. They were wrong, of course, but similar mistakes have been made in every war since then.”

*****

“Glory” was a critical hit. Some writers, particularly the revered New Yorker film reviewer Pauline Kael, overlooked some minor faults and focused on the picture’s undeniable power. “Glory,” she wrote, “is based on fiery, spirit-stirring material that has never before been tapped for the movies.” She gave particular emphasis to “the three black powerhouse actors [who] get to display something besides dignity.” Kael also mentioned another important reason the film touched so many: “ ‘Glory’ shows the high cost of war, and yet finds meaning in the sacrifice.”

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning three—Denzel Washington for best supporting actor; cinematographer Freddie Francis for the lovely, elegiac tone of his color photography; and the best sound award. James Horner won a Grammy for his soulful, stirring score.

The unsung and forgotten hero of “Glory” was writer Kevin Jarre, whose screenplay got Golden Globes and Writers Guild of America nominations for best screenplay. Jarre, son of actress Laura Devon and stepson of composer Maurice Jarre, was, as he told me, “electrified” by the process of researching and writing the screenplay. “A subject like this falls into your lap once in a lifetime, if you’re lucky. Imagine one of the most important moments in the Civil War, in all of American history, and it has been practically forgotten.”

Jarre started the project “almost in a fever. I jumped right in and absorbed every available source on black soldiers in the Civil War and on the 54th Mass in particular.” These included James McPherson’s history on the Union army’s black troops; the book “The Sable Arm”; Shaw’s letters, which are housed at Harvard’s Houghton Library; Lincoln Kirstein’s hugely affecting photo album of the Saint-Gaudens memorial, titled “Lay This Laurel”; and Peter Burchard’s history of Shaw and the 54th, “One Gallant Rush” (its title taken from an editorial by Frederick Douglass that urged young black men to join the regiment: “The iron gate of our prison stands half open. One gallant rush … will fling it wide”).

He kept two poems, framed, on his office wall for inspiration. One was “The Unsung Heroes,” by 19th-century African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, which reads in part:

“A song for the unsung heroes who rose in the country’s need,

When the life of the land was threatened by the slaver’s cruel greed.”

The other framed poem included lines from Robert Lowell’s “For the Union Dead,” the poet’s reflections on Shaw and the monument: “He is out of bounds now. He rejoices in man’s lovely, peculiar power to choose life and die.”

Besides Shaw, Jarre’s three main characters were Private (and later Sergeant) Rollins, played by Morgan Freeman, a laborer who went from burying Union soldiers to fighting alongside them; Thomas Searles (Andre Braugher), an educated free man who grew up with Shaw; and Private Trip (Denzel Washington), an escaped slave who, finally, chooses to fight for his country.

Some historians noted that Jarre took liberties with the facts. For instance, his script depicts more of the former slaves than of the free men who composed most of the 54th’s roster; Shaw’s wife is not mentioned at all; and Shaw is killed in the charge up the hill to Fort Wagner, rather than at the top of the parapet, where he actually died.

Jarre defended his choices, explaining, “I thought we were obligated to represent all the black men who volunteered for service, both slave and free. There were Union regiments of blacks formed in the South comprised only of slaves, but who knew if anyone would ever make a movie about them? I figured this was the chance to tell their story.”

He chose to leave Shaw’s wife out of the story because “[w]e don’t know much about Anna Shaw. They had only been married a short time, so there wasn’t much correspondence to draw on. I felt it was more important to include Shaw’s mother, who was a big influence on him. We took a dramatic liberty with Shaw’s death because we wanted to impress that the men of the 54th were capable of motivating themselves up that hill.”

Jarre’s own story turned out to be one of unfulfilled promise. After “Glory,” he wrote only two other screenplays of significance: “Tombstone,” (1993) with Kurt Russell playing Wyatt Earp and Val Kilmer playing Doc Holliday, and “The Devil’s Own,” about an Irish Republican Army gunman in America, starring Brad Pitt and Harrison Ford. (Jarre was also hired to direct “Tombstone” but was fired after a few weeks, when producers decided the project was moving too slowly.) He died of heart failure in 2011, at age 56.

He ensured, however, that future generations of moviegoers would remember his face, writing himself a small part in “Glory” as the white soldier who almost picks a racially charged fight with Denzel Washington, and then later, as the regiment marches off to assault Fort Wagner, yells out, “Give ‘em hell!”

What isn’t so well remembered is that “Glory,” in the year of its release, was far from the overwhelming box office smash that its later reputation would indicate. According to the internet movie database IMDb, “Glory” was 45th in box office receipts among 1989 films, taking in just under $27,000,000. The 1980s were a time for escapism in American movies, and among the year’s biggest hits were “Batman,” “Look Who’s Talking” and a much more comfortable depiction of race in America, “Driving Miss Daisy,” for which Morgan Freeman was nominated for best actor for his role as a longtime chauffeur.

The reason “Glory” did not do better at the box office is hard to pin down, but according to professor Bruce Chadwick, author of “The Reel Civil War: Mythmaking in American Film,” “Few people knew the actual story of the 54th Massachusetts, so when the movie came out, they were quite surprised.” Chadwick adds that “Glory could never have been made prior to the 1960s and the Civil Rights movement. That was the foundation for movies about racism, and in Glory the filmmakers gave us both racism, redemption, and heroism at the same time.”

Andre Braugher says, “Frankly, I don’t know why ‘Glory’ wasn’t a bigger hit. But I can tell you this—everyone working on it always knew we were doing a very important film.”

Zwick went on to direct such feature films as “Legends of the Fall,” “Courage Under Fire,” “The Last Samurai” and “Blood Diamond,” and won an Oscar for producing “Shakespeare in Love.” “But no film I’ve been associated with made me prouder than ‘Glory.’ People still come up to me after all these years and say, ‘That movie gave me goose bumps.’ And that gives me goose bumps.”

Written by Allen Barra and published by Truth Dig ~ July 18, 2019