When it comes to writing, American kids just don’t cut it. Only 27 percent of eighth grade students achieve proficiency in the subject, according to The Nation’s Report Card.

When it comes to writing, American kids just don’t cut it. Only 27 percent of eighth grade students achieve proficiency in the subject, according to The Nation’s Report Card.

That shouldn’t surprise us given the type of writing instruction which takes place in schools. Today’s writing instruction, a recent op-ed from The Hechinger Report explains, revolves around a child expressing his ideas on paper. Schools seem to believe that students have all the knowledge and inspiration locked up inside them. This knowledge simply needs to be let loose in order to create a written masterpiece.

Not so, declare New York English Language Learner (ELL) experts Hongying Shen and Angel Rodriguez. “A systematic approach to writing instruction is missing from the knowledge base,” they suggest. Students are unfamiliar with the tools they need to write well:

In one specific example, high school students across the city did not know what the conjunctions ‘because,’ ‘but’ and ‘so’ are meant to signal. The Common Core, in part a response to the poor quality of writing nationwide, pushes length and text complexity. But if a large percentage of students cannot identify and use these linguistic tools of thinking even at the sentence level, pushing for rigor without teaching the linguistic resources that provide access to it leaves struggling students further behind.

The solution to this problem is two-fold, report Shen and Rodriguez. The first is to stop relying on “best practices” and instead rely on teachers to evaluate where students are at and what they need. In other words, students need individual attention tailored to perfect their writing skills, not the cookie-cutter methods used on every student.

Shen and Rodriguez go on to say:

The second ingredient is direct, explicit instruction in expository writing strategies that target and close the gaps that teachers find. These strategies improve oral language, deepen students’ content knowledge, and fortify reading comprehension and writing all at the same time.

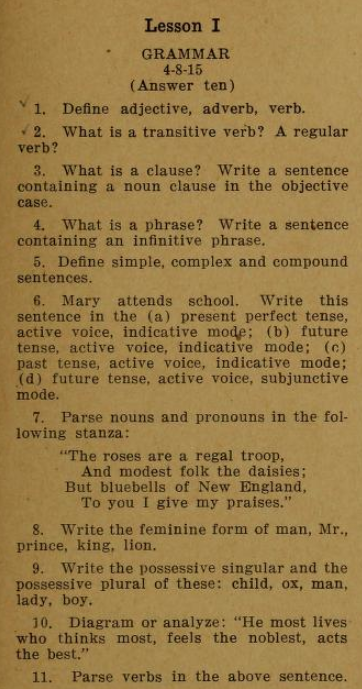

Once upon a time, students mastered the basic building blocks of writing. They read high quality books written by skilled authors. They also learned the components of language and grammar, a fact evidenced by the eighth grade grammar exam from 1915. (To try your hand at some of the questions pictured below, take our short quiz at the bottom of the article.)

It’s easy to view such an approach to writing as archaic. It’s “drill and kill” after all! Such education tactics are supposed to be soul-crushing and undesirable.

It’s easy to view such an approach to writing as archaic. It’s “drill and kill” after all! Such education tactics are supposed to be soul-crushing and undesirable.

But what if we’ve been mistaken about them? Could they be the springboard children need if they’re going to thrive in life?

Author Dorothy Sayers believed they were. In her famous essay, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” Sayer explains how the Trivium — the traditional approach to education — gave children the factual equipment they need to become well-educated adults:

The whole of the Trivium was, in fact, intended to teach the pupil the proper use of the tools of learning, before he began to apply them to “subjects” at all. First, he learned a language; not just how to order a meal in a foreign language, but the structure of a language, and hence of language itself–what it was, how it was put together, and how it worked. Secondly, he learned how to use language; how to define his terms and make accurate statements; how to construct an argument and how to detect fallacies in argument. Dialectic, that is to say, embraced Logic and Disputation. Thirdly, he learned to express himself in language– how to say what he had to say elegantly and persuasively.

At the end of his course, he was required to compose a thesis upon some theme set by his masters or chosen by himself, and afterwards to defend his thesis against the criticism of the faculty. By this time, he would have learned–or woe betide him– not merely to write an essay on paper, but to speak audibly and intelligibly from a platform, and to use his wits quickly when heckled. There would also be questions, cogent and shrewd, from those who had already run the gauntlet of debate.

We seem to have it backward these days. We expect children to come up with their own creative compositions and essays when they have no foundation to build upon. If we reversed course, started with the building blocks of facts and grammar, and then expanded into argument and creativity, would we see far more than 27 percent of the student population leave school as proficient writers and effective communicators?

Eighth Grade Grammar

Define Adverb

What is a Transitive Verb?

What is a Transitive Verb?

What is a Clause?

What is a Clause?

What is a Phrase?

What is a Phrase?

Write the possessive singular and the possessive plural of these” child, ox, man, lady, boy

Write the possessive singular and the possessive plural of these” child, ox, man, lady, boy

Define a complex sentence

Define a complex sentence

Written by Annie Holmquist and published by Intellectual Takeout ~ May 8, 2019

~ The Author ~

~ The Author ~

Annie is a senior writer with Intellectual Takeout. In her role, she assists with website content production and social media messaging.

Annie received a B.A. in Biblical Studies from the University of Northwestern-St. Paul. She also brings 20+ years of experience as a music educator and a volunteer teacher – particularly with inner city children – to the table in her research and writing.

In her spare time Annie enjoys the outdoors, gardening, reading, and events with family and friends.