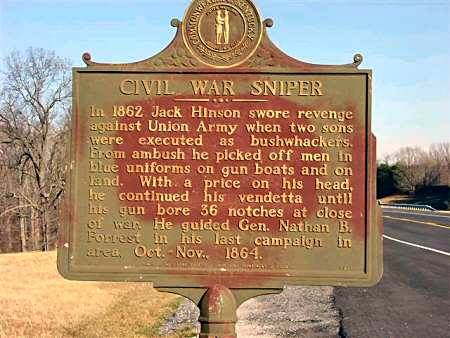

John W. “Jack” Hinson, better known as “Old Jack” to his family, was a prosperous farmer in Stewart County, Tennessee. A non-political man, he opposed secession from the Union even though he owned slaves. Friends and neighbors described him as a peaceable man, yet despite all this, he would end up going on a one-man killing spree.

Jack’s plantation was called Bubbling Springs, where he lived with his wife and ten children. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he was fiercely determined to remain neutral.

Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant

When Union Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant arrived in the area in February 1862, the Hinsons hosted the man at their home. The general was so pleased with the plantation that he even turned it into his temporary headquarters.

Even when one of their sons joined the Confederate Army, while another joined a militia group, Jack remained strictly neutral. They were content to manage their plantation despite the ongoing conflict.

Grant had stayed at the Hinson estate after capturing Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. In taking the last, he secured a vital gateway to the rest of the Confederacy. The Union’s victory at the Battle of Fort Donelson was also its first major one since the start of the Civil War.

His victory also meant that Union troops became a permanent fixture in the Kentucky-Tennessee border where the Hinsons lived. While the family had no problem with that, others did – and the Hinsons would pay dearly for it. In the end, so would many Union soldiers.

Since many in the region were sympathetic to the Confederacy, some turned to guerrilla tactics to deal with the better armed and trained Union soldiers. These were called bushwhackers, because they hid in the woods where they could attack Union troops before fading back into the wild.

It wasn’t just soldiers they went after, however. There were many cases where they’d target Unionist farmers and sympathizers, as well. Still others were not so politically motivated. Some bushwhackers were bandits who took advantage of the deteriorating law-and-order situation to prey on isolated homesteads. In some cases, they even attacked entire communities.

After the fall of Fort Donelson to Union troops, guerrilla attacks on Union soldiers and their supporters increased. As a result, it became policy to torture and execute any suspected bushwhackers without a trial.

In the fall of 1862, Jack’s 22-year-old son George Hinson, and his 17-year-old brother, Jack, went deer hunting about a mile from their home as they always did. Unfortunately, they came across a Union patrol who suspected them of being bushwhackers.

The boys were tied to a tree then shot, after which their bodies were dragged back to town. There the corpses were paraded around the Dover courthouse square as an example of the Union’s zero-tolerance policy toward resistance. The remains were then decapitated and left there, while the heads were brought to the Hinson plantation.

Before the entire family, the heads were stuck on two gate posts as an example of Union justice. The lieutenant in charge wanted to arrest the Hinsons for their relationship to the two alleged bushwhackers but was informed about Grant’s stay on the property. He was also told that the major general would not take kindly to any mistreatment of the surviving Hinsons, so they were left alone.

That was the lieutenant’s second mistake of the day.

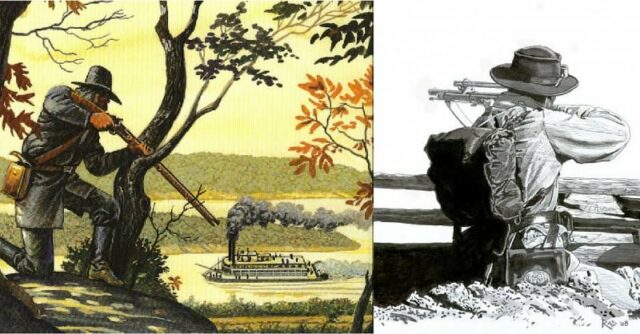

The only known image of Jack Hinson

Of Scottish-Irish descent, Jack could not let the murders of his sons go unpunished. He buried his children’s remains, then sent the rest of his family and slaves to West Tennessee to stay with relatives.

He then commissioned a special 0.50 caliber rifle with a percussion-cap muzzle-loader. Besides its lack of decorative brass ornamentation, this rifle was also unique because it had a 41” long octagonal barrel that weighed 17 pounds. The length of the barrel ensured that he could accurately hit targets from half a mile away.

As to the octagonal shape, it was based on the Whitworth Rifle. With its hexagonal barrel, it could shoot farther (2,000 yards) and more accurately than the Pattern 1853 Enfield (1,400 yards) with its traditional round rifled barrel.

Moving into a cave above the Tennessee River, Jack became a bushwhacker at the age of 57.

His first target was the lieutenant who ordered his sons shot and beheaded. The man was killed as he rode in front of his column. The second target was the soldier who placed the heads on the gateposts. It didn’t take the Union long to connect the dots, so they burned down the abandoned Hinson plantation.

The British Whitworth sharpshooting rifle which served as the basis for Jack’s own

The Tennessee and Cumberland rivers were major transport hubs, so he frequented both. From his higher vantage points, he targeted Union boats, picking off captains and officers, as well as disrupting the flow of river traffic.

The most spectacular story of his sniping career was when an entire boat of Union soldiers surrendered to him. After Jack fired on the boat, the captain thought he was being attacked by Confederate soldiers. To avoid further bloodshed, the captain beached his boat, raised a white tablecloth, and waited to be captured. But Jack couldn’t possibly handle them all, so he retreated and let them wait.

Though he remained apolitical, he began helping the Confederate Army. In November 1864, for example, he guided Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest to Johnsonville to attack its Union supply center.

With help from the locals and by constantly staying on the move, he avoided capture despite the massive manhunt for him. His family was not so lucky, however. Two of his younger children had died of disease, while the son who joined the army also died, as did another during a guerrilla raid.

Jack survived the war and cut 36 circles in the barrel of his rifle to mark the number of Union officers he killed. Union records, however, blame him for over 130 kills – though it’s believed that he may have killed “only” a little more than 100.

Jack died on 28 April 1874 and lies buried in the family plot in Cane Creek Cemetery.

Written by Shahan Russell and published by War History Online ~ April 16, 2018

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE: