Elizabeth Cotten was never famous, and almost slipped into total obscurity

Domestic, 71, Sings Songs of Own Composition in ‘Village,’” ran a New York Times headline in November of 1965. The piece, about a woman with “five grandchildren, nine great-grandchildren, a guitar, a banjo and about 20 old-time folk songs,” heralded the return of then-unknown folk songstress Elizabeth Cotten, who was poised to play the Gaslight Cafe, on Macdougal Street in a Greenwich Village still quaintly set off by single quotation marks.

Though many had never heard Cotten’s name, they’d heard her most popular song, “Freight Train,” which became a hit when the crunchy folk ensemble Peter, Paul and Mary recorded and released it in 1963. (Many others have since recorded their own versions of the tune.) It was a song she’d written at 11 years old. But though it became a standard, Cotten was never famous, and she’d slipped into total obscurity for four decades while raising a family of her own and working as a domestic in North Carolina, then New York City and Washington, D.C.

While working briefly at a department store in the late 1940s, Cotten helped a lost little girl find her mother, and was offered a job as a maid for the family. The little girl was Peggy Seeger, who would go on to find folk-singing fame, and her mother was Ruth Crawford Seeger, a composer and folk music specialist. Cotten began doing the “washing, cleaning and baking” for the family of folk lovers — Charles Seeger, the patriarch, was a well-known musicologist; brother Mike was a musician and folklorist; and Pete Seeger was Peggy’s half brother — and it wasn’t long before she picked up a guitar and blew their minds.

‘’When she worked for us,” Mike Seeger told the New York Times in 1983, “I’d be playing a song in the kitchen and she’d be doing something there. Then she would play the song back to me and say, ‘Do you know that song?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, I’m not sure,’ and she’d say, ‘Well, you just sang it and played it.’ But it would sound different — she would make it her own.’”

Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten was born in 1893 near Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Her mother was a cook, and her father was “a sometime moonshiner who also set dynamite in iron mines.” Libba Cotten began borrowing her brother’s banjo (against his wishes) from a very young age — “My head was always full of music,” she said — and around age nine she saved her wages and bought her own Sears, Roebuck guitar. (She was already working as a domestic, making 75 cents a month.)

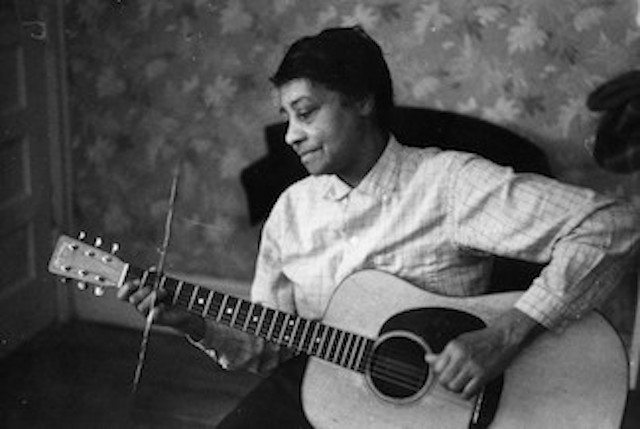

Because she was left-handed, Cotten taught herself to play by turning her brother’s banjo upside down so her right hand was on the fretboard and her left picked the strings. Most notably, this also meant she played the treble notes with her thumb and the lower bass notes with her fingers. Her smooth, masterful two-finger picking, which sounds warm and full, became her signature style, known as “Cotten-picking,” and it’s worth watching vintage video of a cardiganed Cotten playing “Freight Train” or “In the Sweet By and By,” her eyes gently closed as she plucks the notes.

Although it was an outgrowth of the Old Left of the 1930s and ’40s and was largely espousing the message of social progressivism, the commercial folk music revival of the 1960s was, in the words of sociologist William G. Roy, “distinctly white.” In his 2010 book Reds, Whites, and Blues: Social Movements, Folk Music, and Race in the United States, Roy writes that although the sixties folk project was dominated by white musicians like the Seegers, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, and Peter, Paul and Mary, the scene loved the pared-down contributions of those they saw as the “real” authentic people. “The cultural elite of the folk project have valorized folk music precisely because it is the music of the common folk,” Roy writes. “The more marginal, humble, and unsophisticated the makers of music the better, at least from the perspective of the educated, urban folk enthusiasts.” While it may sound cynical, Roy claims that this “inversion of cultural hierarchy” was one of the things that drew left-wing activists to folk music in the first place. As the “people’s music,” it could be used to “galvanize social movements and especially to bridge racial boundaries.” Folk music became hugely influential to the civil rights movement, though Roy points out that activists were more likely to use the songs for their unifying emotional resonance than to try to sell records, as their Old Left brethren had.

For her part, Elizabeth Cotten was about as “marginal” and “humble” as could be, but her music had sophistication, bearing the nimbleness of a musical master and the mark of a lifetime of experience. She played her first live show with Mike Seeger in 1959 and before long had launched one of the more glamorous careers among grandmothers, at the intersection of folk and blues, playing alongside stars like Taj Mahal and Muddy Waters. Cotten also played the legendary Newport Folk Festival in 1968, as well as the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Smithsonian Festival, and others. She later relocated to Syracuse, New York, though she was frequently on the road. Cotten recorded seven albums and toured nationally and abroad for the duration of her life. She died in Syracuse at age 95.

In 1985, at 93, Cotten won a Grammy for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording for her album Elizabeth Cotten – Live! “I was so excited when they gave me this,” she told the Elmira, New York Star-Gazette. “I was sitting in my seat just watching and listening and when the man said my name I got so weak and scared I didn’t think I could go up there myself.” But Cotten did ascend the stage to accept the award. “All I could think of to say was ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you. If I had my banjo with me I’d play you a tune.’”

Written by Nina Renata Aron for Timeline ~ February 6, 2018