The story of a man who showed the world how a peaceful, non-governmental system can flourish.

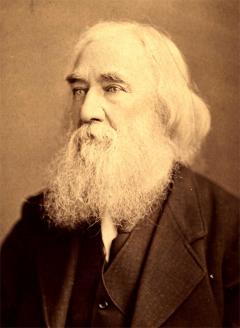

Lysander Spooner

This is a story about a philosopher, entrepreneur, lawyer, economist, abolitionist, anarchist—the list goes on. As his obituary summarizes, “To destroy tyranny, root and branch, was the great object of his life.” Although he is rarely included in mainstream history, Lysander Spooner was an anarchist who didn’t merely preach about his ideas: He lived them. No example illustrates this better than Spooner’s legal battle against the US postal monopoly.

Born in 1808 in Athol, Massachusetts, Lysander Spooner was raised on his parent’s farm and later moved to Worcester to practice law. Eventually, he found himself in New York City, where business was booming—but not for the Post Office.

The Postal System of the 1840s

In Spooner’s day, government subsidized the cost of building infrastructure used for mail routes. Postage rates paid for these subsidies, which in turn made the rates expensive. For example, in 1840 it cost 18.75 cents, over a quarter of a day’s wages, to send a letter from Baltimore to New York.

Corruption was another issue facing the post office. Positions appeared to change after each election cycle, indicating political cronyism. Congress was also under pressure from the coach contractor lobby, and favorable postage routes were often given to contractors with political connections. Thanks to a legal monopoly it had enjoyed since the Confederation, the Post Office remained the sole legal mail business despite its skyrocketing costs and corruption.

In his book Uncle Sam, The Monopoly Man, William Wooldridge describes how high postal costs led some to defy postal laws: Traveling individuals doubled as temporary, private postmen. By the 1840s, these illicit services were chipping into government revenues. Eventually, a court ruled it legal for individuals (but not companies) to carry mail. As a result, underground mail enterprises sprung up. Agents covertly used the existing rails, coaches, and steamboats to transport letters. It is estimated that in 1845, a third of all letters were transported by private mail firms.

Spooner’s Resistance

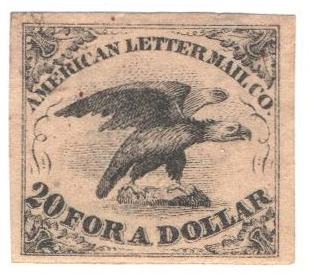

Spooner, who saw the postal monopoly as unjust, was not content to operate in secrecy like most. Instead, he announced the founding of his private mail company to the US Postmaster General, writing on January 11, 1844: “I propose soon to establish a letter mail from Boston to Baltimore. I shall myself remain in this city, where I shall be ready at any time to answer any suit.” Spooner’s explicit purpose was to challenge the post office’s monopoly; his advertisement boldly claimed: “The Company design also (if sustained by the public) thoroughly to agitate the question, and test the constitutional right of free competition in the business of carrying letters.”

According to Spooner’s book, Who Caused the Reduction of Postage?: Ought He to Be Paid?, Spooner’s “American Letter Mail Company” was distributing mail two weeks later. Delivery occurred daily between New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Additionally, Spooner’s five-cent stamps were drastically cheaper than the post office’s rates.

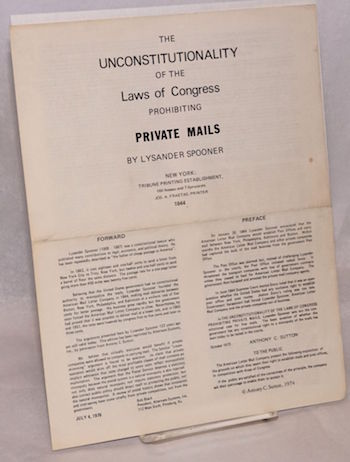

Lysander Spooner justified his business to the public in his 1844 pamphlet, “The Unconstitutionality of the Laws of Congress, Prohibiting Private Mails”: He argued that although the Constitution granted Congress the power to “establish post offices and post roads,” this only gave Congress the authority to create a postal service, not to prohibit competition. For comparison, the same Constitutional clause gave Congress the power “to borrow money,” yet no one claimed that only Congress could do that. If a postal monopoly was legitimate, the Constitution would have granted a “sole and exclusive” power to create a postal service like the Articles of Confederation had done.

Lysander Spooner justified his business to the public in his 1844 pamphlet, “The Unconstitutionality of the Laws of Congress, Prohibiting Private Mails”: He argued that although the Constitution granted Congress the power to “establish post offices and post roads,” this only gave Congress the authority to create a postal service, not to prohibit competition. For comparison, the same Constitutional clause gave Congress the power “to borrow money,” yet no one claimed that only Congress could do that. If a postal monopoly was legitimate, the Constitution would have granted a “sole and exclusive” power to create a postal service like the Articles of Confederation had done.

The Post Office Strikes Back

Constitutional or not, the government defended its monopoly. Six days after Spooner’s company began, Congress introduced a resolution to investigate the establishment of private post offices. Meanwhile, Spooner’s company was booming. As the US postal revenue went down, the government threatened those who were caught serving private mail carriers. In his book, Spooner noted that by March 30, he and his agents were arrested while using a railroad in Maryland to transport letters. Spooner, busy with multiple legal challenges, was released on bail by mid-June (“Mr. Spooner’s Case.” Newport Mercury, June 15, 1844.)

People had become accustomed to inexpensive mail, and Congress reluctantly acknowledged the need to lower postal rates. Still, officials stressed that “it was not by competition, but by penal enactment, that the private competition was to be put down” (The Congressional Globe, 14. Washington: The Globe Office, 1845, page 206). In March 1845, Congress fixed the rate of postage at five cents within a radius of 500 miles. The post office adopted tactics that private carriers used to increase efficiency, such as requiring prepayment via stamps. These changes turned the post office’s budgetary deficit into a surplus within three years.

The reforms were a victory for the public, but they contributed to the end of Spooner’s company. Legal fees, along with the increased usage of the post office, brought about Spooner’s downfall. As Benjamin Tucker, Spooner’s mentee, described: “[A]s the carrying of each letter constituted a separate offense, the government was able to shower prosecutions on him and crush him out by loading him with legal expenses.”

Spooner went back to Athol and dedicated himself to the abolitionist cause as the Civil War drew near. After the war, he advocated for the right to secession and continued to write on his anarchist views. Finally, on May 14, 1887, Lysander Spooner died peacefully in his room, surrounded by his books and pamphlets.

A Lasting Legacy

A Lasting Legacy

In contrast to other activists who tried to lower postal prices through politics, Spooner’s competitive approach de facto forced the government to respond. So although the postal monopoly remained, Spooner’s conflict led to a nearly 75 percent reduction in postal rates, and his legacy remains as the “father of cheap postage in America.”

In 1970, the United States Postal Service replaced the Post Office Department of Spooner’s day. However, the legal monopoly persists, along with the legal battles. In 1971, a company delivering Christmas cards at a lower rate than USPS was stopped by a court injunction. Until 1993, Equifax had been sending letters via FedEx. This ended when company headquarters were raided by armed USPS agents, and the company was fined 30,000 dollars. Even in 2018, President Donald Trump attacked the online retailer Amazon for damaging post office revenues.

Despite this, Lysander Spooner’s ideas remain relevant today. Murray Rothbard, founder of the anarcho-capitalist movement, drew inspiration from Spooner. Gerard Casey notes in his book Murray Rothbard that it was Rothbard’s synthesis of Spooner’s beliefs and those of other philosophers that shaped modern libertarianism.

Rothbard admired Spooner most for his action-oriented vision. It is easy to denounce government; it is much harder to show how a peaceful, non-governmental system can flourish. With his postal company, Spooner did exactly that. Instead of passively waiting for government reform, Spooner illustrated how individuals could create their own solutions to government problems.

This entrepreneurial version of government resistance persists today in everything from black markets to Bitcoin. The fully anarchist society Spooner envisioned may never happen, but as long as individuals with Spooner’s enterprising spirit exist, “anarchy” will always have a place in society.

Editor’s NOTE: At the time of the above publication, the U.S. Postal “service” prepares to increase the cost of a First Class (Forever?) stamp by 10 percent, from 50 cents to 55 cents. ~ JB

Written by Naomi Mathew for the Foundation for Economic Freedom ~ January 12, 2019