Thomas Paine’s Revolutionary War pamphlet may have changed the course of American history.

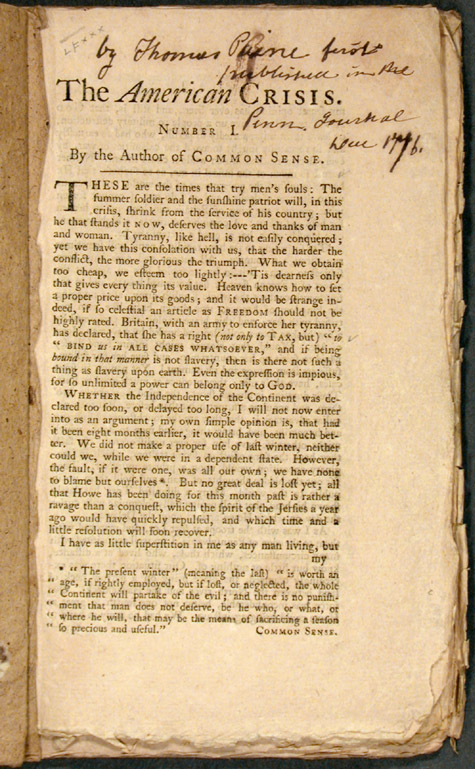

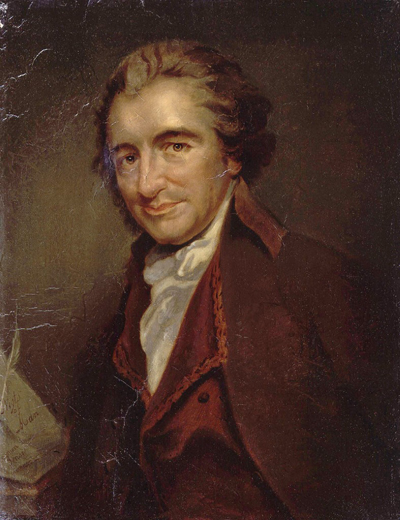

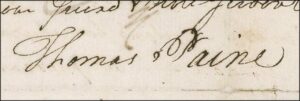

On December 19th, 1776, the firebrand journalist and activist Thomas Paine (1737-1809) published the first volume of his political pamphlet The Crisis (also known as The American Crisis). The Crisis would feature five more volumes over the next twelve months, documenting much of the first full year of the incipient American Revolution against England. Paine would go on to release thirteen additional volumes between 1778 and the Revolution’s 1783 conclusion, continuing to trace the conflict’s evolution and to add his passionate support to the colonist cause at each stage.

On December 19th, 1776, the firebrand journalist and activist Thomas Paine (1737-1809) published the first volume of his political pamphlet The Crisis (also known as The American Crisis). The Crisis would feature five more volumes over the next twelve months, documenting much of the first full year of the incipient American Revolution against England. Paine would go on to release thirteen additional volumes between 1778 and the Revolution’s 1783 conclusion, continuing to trace the conflict’s evolution and to add his passionate support to the colonist cause at each stage.

That December 19th number begins with some of the most eloquent and inspiring lines in American history:

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: ‘Tis dearness only that gives everything its value.

Those impassioned words offer inspiration for resistance and persistence in the face of the darkest times and challenges. But if we add biographical and historical contexts for this seminal American author, we gain an even deeper sense of the inspiration he can offer us in these modern times.

Paine’s biography highlights the depth and breadth of his activist roots. He had immigrated to America from England only two years prior, in November 1774, arriving in Philadelphia with little more than a letter of recommendation from Ben Franklin. Franklin’s impression of Paine as “an ingenious, worthy young man” was based in part on the perspective of a mutual friend, the London mathematician and politician George Lewis Scott. But it was also based on Paine’s own burgeoning public and activist career, highlighted by his 1772 article “The Case of the Officers of Excise.” In that work Paine launched a lifelong career fighting for the rights of minorities and the common man against entrenched, powerful interests.

Paine’s biography highlights the depth and breadth of his activist roots. He had immigrated to America from England only two years prior, in November 1774, arriving in Philadelphia with little more than a letter of recommendation from Ben Franklin. Franklin’s impression of Paine as “an ingenious, worthy young man” was based in part on the perspective of a mutual friend, the London mathematician and politician George Lewis Scott. But it was also based on Paine’s own burgeoning public and activist career, highlighted by his 1772 article “The Case of the Officers of Excise.” In that work Paine launched a lifelong career fighting for the rights of minorities and the common man against entrenched, powerful interests.

Paine continued those efforts, and extended them into the realm of journalism, not long after his arrival in America. When Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken founded Pennsylvania Magazine in February 1775, with the intent of making it the first “American magazine,” Paine contributed two pieces to the inaugural issue. A month later Aitken would name Paine the editor, and in that role Paine would both write and publish a great deal of his political and social activism, including support of controversial causes like the abolition of slavery: in March 1775 the magazine published the anonymous abolitionist essay “African Slavery in America” (a piece that Benjamin Rush would later attribute to Paine himself), and in April 1776 it published ex-slave Phillis Wheatley’s stirring Revolutionary poem “To His Excellency General Washington.”

Between those journalistic efforts and his January 10th, 1776, Revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense, Paine had by 1776 established himself as one of America’s most impassioned and vital political and social voices. But by December of that year, much had changed in the American Revolutionary situation, and more exactly the cause was at a strikingly low point. Washington and the Continental Army had been involved for months in the New York and New Jersey campaign, and that campaign was going poorly: by early December Washington had lost a number of engagements with the forces of British General William Howe, and the American troops had withdrawn across the Delaware River, leaving New York and New Jersey in mostly British hands. Congress had even withdrawn from the city of Philadelphia, and it seemed quite possible that both the Continental Army and the Revolution itself would not survive this first post-Declaration of Independence winter.

This was certainly not a moment when summer soldiers and sunshine patriots could hope to find much warmth, a particularly fraught period that makes clear why Paine capitalizes “NOW” in his pamphlet’s opening lines (his only such capitalization there). It’s not just that Paine’s pamphlet was directly inspired by surrounding events, though – it also quite possibly influenced those events. A few days after the pamphlet’s initial publication, Washington likely read a reprint aloud to his men, with whom he was camped in Pennsylvania. The historical record is ambiguous on whether the general actually read The Crisis aloud, as this article traces, but Washington and the army at least knew of and were inspired by the pamphlet soon after its publication. On the night of December 25th, Washington led many of those troops in the famous crossing of the Delaware, a surprise attack on the British forces at Trenton that significantly shifted the course of not only this campaign but the whole early Revolutionary conflict.

This was certainly not a moment when summer soldiers and sunshine patriots could hope to find much warmth, a particularly fraught period that makes clear why Paine capitalizes “NOW” in his pamphlet’s opening lines (his only such capitalization there). It’s not just that Paine’s pamphlet was directly inspired by surrounding events, though – it also quite possibly influenced those events. A few days after the pamphlet’s initial publication, Washington likely read a reprint aloud to his men, with whom he was camped in Pennsylvania. The historical record is ambiguous on whether the general actually read The Crisis aloud, as this article traces, but Washington and the army at least knew of and were inspired by the pamphlet soon after its publication. On the night of December 25th, Washington led many of those troops in the famous crossing of the Delaware, a surprise attack on the British forces at Trenton that significantly shifted the course of not only this campaign but the whole early Revolutionary conflict.

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze

It’s easy to see such historical moments as inevitable in hindsight, but of course it was anything but, just as the outcome of the Revolution was far from certain in December 1776 (and would be precarious for many years to come). Those uncertainties help us understand the existence of Paine’s pamphlet – and also help us see the role that Paine’s inspiring words played in helping carry those Revolutionary efforts forward. As we move deeper into our own winter of discontent, Paine’s words, life, and perspective can offer inspiration to us today.

Written by Ben Railton for The Saturday Evening Post ~ December 18, 2018